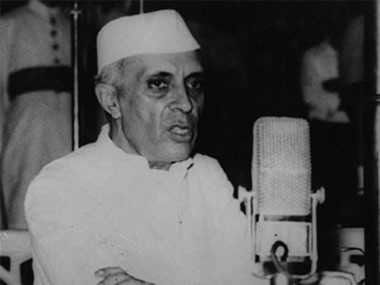

The ongoing culture and history wars in India now have an added new dimension, the unedifying spectacle of the ‘Nehru Wars’ as the great man’s 125th birth anniversary celebrations get underway. The Congress party, by not inviting Prime Minister Narendra Modi and other Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leaders to its international conference on Jawaharlal Nehru, has shown how little it knows about India’s first prime minister. Vitriol and venomous attacks never deterred Nehru from engaging with his opponents; indeed that was one of his many appealing qualities.

Nehru’s first cabinet in 1947 consisted of some of his fiercest critics and this ability to rise above petty differences for a cause was the hallmark of his greatness; his self-deprecating words, “We are little men, serving a great cause, but because the cause is great something of that greatness falls upon us also”, capture the essence of Nehru.

Historian Ramachandra Guha says that if the 1920s and 1930s were the Age of Gandhi, then the 1940s and 1950s were the Age of Nehru. His twilight years began just as the 1950s were drawing to a close and the disastrous 1962 war with China was indeed the nadir. His reputation in tatters, his foreign policy of nonalignment discredited and the halo around him dimmed forever. Yet, many asked just a year before his death ‘after Nehru, who’? While others asked ‘after Nehru what’? This echoed the indispensability of Nehru. Five decades later we are, however, confronted with ‘why Nehru’ and why not Sardar Patel, his contemporary — and a rival of sorts.

Modi’s rise has reignited the Patel-versus-Nehru controversy. Indeed it was Modi who energetically fuelled this debate to cleverly outwit the Congress. By churlishly not inviting Modi to the conference, some of these questions will continue to gather saliency and the public at large will ponder on the many ‘ifs’ of history; perhaps the Partition could have been avoided, the Kashmir problem would never have arisen and the debacle of the 1962 would not have occurred.

The Nehru conference should have confronted these issues; the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and BJP, who have consistently posited that India paid a heavy price for choosing Nehru as its first prime minister, should have been invited to the conclave so that these questions could have been discussed thread bare. Nehru, the architect of modern India deserved no less; hagiography belittles the man. The Congress party lost the opportunity to set Nehru free.

The choice of Nehru as India’s first prime minister was made by none other than Mahatma Gandhi and to suggest that Gandhi was persuaded to do so by Motilal Nehru, Jawaharlal’s father, is patent nonsense. Next, it was at Gandhi’s behest that the country had a Nehru-Patel combine at the helm, which worked well despite serious differences of opinion between the two. More importantly, both were equally responsible for the Partition, working hand in glove to thwart Gandhi. Such was the trust between the two to steer India through those troubled times.

On Kashmir and China, Nehru cannot be spared and Patel may have handled it better. On China, Nehru erred grievously and no Nehruvian, however, enamoured he or she maybe of his or her hero, can let him off on this Himalayan blunder. The Kashmir imbroglio is more complicated. Nehru made mistakes but let it not be forgotten that without Nehru, India may never have acquired this princely state. With Patel at the helm, Shaikh Abdullah would never have chosen to go with India and annexation was near impossible without Abdullah’s acquiescence.

All this is history. So what of Nehru’s relevance in contemporary India? In an extremely well-argued essay, Sunil Khilnani recently said: “To young Indians, Nehru might appear as an antique. But their lives rest on the political wager he took — of Liberalism. Nehru’s was an immensely risky strategy. It manifested a profound faith and trust in the people of India — far deeper than that shown by Gandhi, always the paternalist; or by [B.R] Ambedkar or Patel, always suspicious of their compatriots.”

Modi, by talking of development and less of sectarian differences, is indeed paying homage to Nehru and his exhortations about the “new temples of resurgent India”. Modi’s economic philosophy is the very antithesis of Nehru but his ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas’ [with all, development for all] is pure Nehruvian thinking. Among Nehru’s many bungles, economic policy was one, but a careful reading will reveal that much of the hard lifting done during the early years, until the end of the first five year plan, was spot on.

The Nehru conference should have devoted a session with the entire phalanx of the Hindu right on board to debate Nehru’s mistakes as also to ask searching questions about RSS icons like [M.S] Golwalkar and [K.B] Hedgewar and their thoughts on secularism and the Muslims of India. Many of today’s avid supporters of Modi and the BJP may be unaware that neither of the RSS grandees took any part in the freedom struggle. Neither went to prison, furthermore it is their current favourite Patel who had banned the RSS after Gandhi’s assassination.

Ravi Menon is a Dubai-based writer, working on a series of essays on India and on a public service initiative called India Talks.