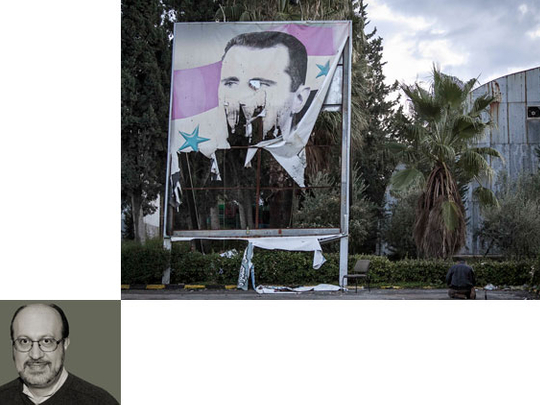

The predicament over Syria remains appalling and even after 20 months of conflict with no end in sight, the best that could be said is that the diplomatic option to settle the uprising is withering on the proverbial vine. Still, looming dangers confront the Syrian Arab Army (SAA), especially after Bashar Al Assad prepares to cede power to a successor regime. Can the SAA be saved?

If Russian and Chinese vetoes were cast for global interests rather than to serve the hapless Syrian population, and if a myriad Arab League States and UN peace missions were permanently placed in abeyance, fresh concerns over a putative Syrian use of chemical weapons finally mobilised western powers to consider some sort of military intervention. Yet, what the Syrian revolution demonstrated was the lamentable performance of the Syrian Army, incapable of defeating ragtag fighters and defectors.

To now assume that the SAA, or what is left of it, can actually mount a sophisticated operation involving the deployment of chemical weapons is sheer lunacy. Still, coordinated war drums can be heard louder than at any other time, as major western powers gear up for some form of intervention to usher in a regime change as well as to prevent a dangerous division of the country into ethnically semi-homogeneous statelets.

Admittedly, France is actively engaged in funding opposition groups around Aleppo, while the United Kingdom is considering specialised military training to elements fighting the Al Assad regime. There is even a discussion of an international coalition to support Free Syrian Army (FSA) units with air and naval power. In addition to significant humanitarian assistance, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, along with Jordan and Turkey, continue to provide light military equipment, although the FSA personnel procure the bulk of the hardware from defecting SAA forces.

Estimated at less than 300,000 active duty personnel before the 2011 uprisings, the SAA experienced a steady emasculation and probably deploys less than 200,000 soldiers today. To thus reach the conclusion that the SAA is nothing more than a shadow of its advertised self would indeed be an understatement, given its mediocre performance during the past two years.

Amazingly, and rather than liberate the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, the SAA is tasked to destroy Syria one building at a time. Roaming tanks in city and village squares, launching artillery against historic monuments, destroying churches and mosques allegedly because “rebels” sought refuge in such dwellings — all of these acts and many more illustrate the SAA’s ideological bankruptcy. Even worse, by engaging civilians, the SAA commits an egregious error that is bound to affect it over the long term, namely that one seldom destroys the source of its legitimacy.

What will be the consequences of such breaches after the Baath Party cedes power to a post-revolutionary government is anyone’s guess. Nevertheless, what is certain is that the SAA cannot possibly survive in its current state, which literally ensures its demise.

No matter how unpalatable that option, the time to plan for a post-SAA set-up is overdue, something that the National Coalition for Syrian Revolutionary and Opposition Forces [NCSROF] must address if it wishes to avoid the 2003 and 2004 experiences with the Iraqi Army. Shaikh Mu’az Al Khatib, the NCSROF president, and his two vice-presidents Suhair Al Attassi and Riad Saif may have their plates full, but all three ought to avoid the interminable disputes that coloured Syrian National Council (SNC) meetings under the leaderships of Burhan Ghalyoun, Abdul Basit Sa’idah and George Sabra. Simply stated, they must not ignore the military roles played by active Islamist groups in Aleppo province, including the two most important ones — the Al Nusra Front and Liwa Al Tawhid.

To be sure, a huge humanitarian crisis will preoccupy opposition leaders once they attain power, though one of the critical priorities must also be the ability to ensure at least a semblance of security. Such an objective will require a steady hand that can amalgamate Islamist-linked paramilitaries, led by the 10,000-strong Jabhat Al Nusrah, and many others, into the nascent army. Moreover serious thought must be given to their systematic eradication. Syrians ought to draw clear lessons from Iraq, Libya, Tunisia and especially Egypt, precisely to avoid a perpetual cycle of violence courtesy fallen dictatorships.

Last but not the least, opposition leaders must also speak clearly to Syrians in general and armed fighters in particular and insist on discipline to prevent revenge killings against SAA units. There is no denying that revolutionary forces have been far more lethal in recent months and that many may refuse to be demobilised. That is the core challenge as Damascus rebuilds the Syrian Army.

One ought to consider channelling the energies of men under arms to various reconstruction projects, both to avoid a protracted civil war, as well as restart the crippled economy. Another step would be to appoint truly professional officers to reinvent the units that once stood against the mighty French Army of the Levant, to once again protect Syrians.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of Legal and Political Reforms in Saudi Arabia.