In early June 2009, President Barack Obama stopped in Riyadh to consult with King Abdullah Bin Abdul Aziz, before he flew to Cairo where he delivered a key — some called it a high-stakes — speech whose goal was to ease long-held Arab and Muslim grievances against the US. At the time, Obama informed the monarch that Washington wanted to tell the truth to Muslims everywhere and many applauded his Egyptian performance. Obama orated that whatever differences existed, over staunch support for Israel, counter-terrorism policies and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, these need not enlarge the gulf further.

The Saudi ruler welcomed his guest and declared that Obama was “a distinguished man,” as hundreds of millions applauded the president’s foresight, and generosity.

Optimism prevailed after decades, during which many promises — Franklin Roosevelt’s pledges over Palestine that were cavalierly dismissed by Harry Truman, or Richard Nixon’s guarantees to King Faisal during the 1973 Arab-Israeli War — were reneged. Both Abdul Aziz and Faisal forgave Washington, but never forgot how easy it was for American administrations to break lofty assurances that, in part, explained Riyadh’s caution even if very close security ties were forged between the two nations as best demonstrated in the 1991 War for Kuwait.

Still, despite palpable tensions over the creation of Israel and the 1973 Arab oil embargo, the US-Saudi bilateral relationship persevered. At no time were policy differences allowed to rock the security foundations that united the two countries. To be sure, 9/11 altered the equation, though all concerned understood that a rogue operation would not define relationships that developed over more than 75 years. Even the post-2011 Arab Uprisings, which muddled everyone’s crystal balls in dealing with such cases as Egypt and Syria, among others, were tangential matters. The major hurdle was Washington’s reluctance to accept Riyadh as a nascent regional power that gained preeminence in the Muslim world in general and the Arab world in particular.

This was the heart of the matter and while Saudi Arabia would never dispatch a naval armada close to US shores, it intended to lead without fear, precisely to protect and defend its national security interests. Of course, pundits claimed that the ageing king was too preoccupied with other concerns and that Saudi Arabia was excessively burdened with serious socio-economic shortcomings for any meaningful changes to occur. Such assertions were inaccurate and it behoved President Obama, as well as his successors, to come to terms with the Kingdom’s will-to-power. Therefore, and beyond “fence-mending,” the mid-March trip ought to be courageous, to prevent Saudi Arabia from going its “own way” since that would serve neither country’s interests.

No doubt, conversations will be sincere and frank and while they will inevitably be courteous — few Saudis have the habit of displaying anger either in public or in private — disagreements over two specific issues, Iran and Syria, need to be handled with utmost care.

Lest one conclude that Riyadh wished to perpetuate religious differences with Tehran over the Sunni-Shiite theological schism, it was worth noting that the core dispute was over political leadership, which predated Islam. Even before 1932, Riyadh perceived Tehran as a regional hegemon, which was a universally shared perspective. When one added to this equation a healthy nuclear weapons programme that may well have forced western powers to acquiesce to its inevitability, the Saudi perception of Iran as a major security threat becomes crystal clear. Even worse, Riyadh’s concerns reached new heights after the Obama administration opted to overlook Iran’s power projection into Iraq and Syria and preferred to re-engage Iran instead.

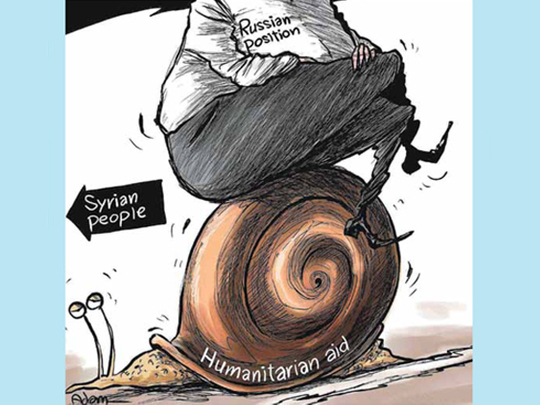

Given the ongoing spectacle in the Levant, Saudis wondered what would have happened in 1990 if Saddam Hussain invaded Syria, instead of occupying Kuwait? Would leading western powers have organised Syria’s liberation or, more likely, would the United Nations have embarked, as it is currently doing, on interminable Geneva negotiations? The questions were not academic for they highlighted fundamental differences between Riyadh and Washington over the Syrian killing fields. While it was customary to blame Russia, China, Iran and Hezbollah for the assistance they provided the Ba‘ath regime in Damascus to do as it pleased, Saudi Arabia did not accept that the uprising, initially peaceful and non-sectarian, was allowed to degenerate into an inferno while the world watched. One simply could either accept or reject the abominable occurrences and Saudi Arabia refused to just observe as civilians were subjected to brutal attacks on a daily basis, simply because past engagements in Iraq and Afghanistan were too costly.

It was with that goal in mind that it provided financial aid, along with limited military assistance, to the Free Syrian Army. Frequent accusations soiled the discussion — that Riyadh was a main conduit of advanced weapons — though that was not the case. Moreover, even Washington now recognises that extremist groups like the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria and Jabhat Al Nusra, among others, are brilliant creations by the Al Assad regime with full Iranian backing, to give the impression that Damascus is engaged in a sectarian war. None of these extremist groups received Saudi backing and, even more pertinent, King Abdullah issued decrees that essentially condemned Saudi citizens who fought in Syria, which was a further assumption of responsibilities.

At its current pace, the Syrian civil war is likely to take years to end, with unforeseen costs to all concerned — which was what Riyadh loathed. It sought peace and security to prevail everywhere throughout the Arab world and expected Obama to acknowledge these wishes. In so far as Saudis are a pragmatic people who harbour no ambition to transform the Kingdom into a superpower armed with nuclear warheads, it behoves Washington to assess Riyadh’s intrinsic values, which Obama fully understands — even if his past nonchalance created the current rift. In mid-March, one hopes that he will reset the clock, to best serve US interests.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of Legal and Political Reforms in Saudi Arabia (London: Routledge, 2013).