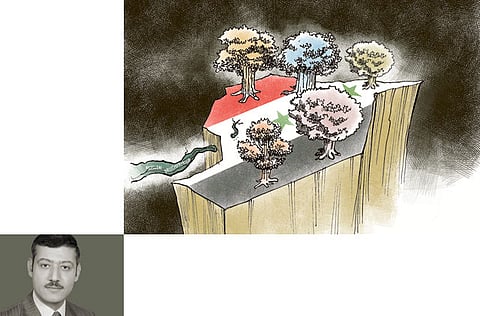

Brotherhood faces Damascus challenge

It will have to start from scratch to establish itself as a credible political force

Last week, the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood (Al Ikhwan) held its first national conference in 30 years in Istanbul. The meeting brought together leaders and members of the organisation for the first time since its exit from Syria in early 1980s. The meeting fed speculations that the group may be preparing to return home should the regime of President Bashar Al Assad collapse.

In fact, since the breakout of the uprising almost 17 months ago, the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood has been trying to re-establish itself as a major force in the country’s political life.

The Egyptian presidential elections in which the Muslim Brotherhood succeeded — after 80 years in opposition — in putting its candidate in the presidential palace has also revived hopes that in Syria too the Brotherhood could realise its long-awaited dream of ruling the country.

Yet the different historical experiences of the organisation in Syria and Egypt could make its task in Syria much more difficult, though not impossible.

One reason for this is that while the Egyptian Brotherhood was tolerated under the Anwar Sadat and Hosni Mubarak regimes, in Syria it has been outlawed for over three decades and affiliation with it was punishable by death.

Inactive and mute within Syrian society for more than 30 years, the Syrian Brotherhood lacks any form of organisation on the ground. If it wants now to establish itself as a credible political force, it would have to start from scratch.

However, another impediment to these efforts remains. In Syria, the bloody history of conflict between the Syrian Brotherhood and the ruling Baath party left deep scars on society.

Armed conflict was unavoidable between two completely different but equally extreme ideologies and worldviews: Secular fundamentalism represented by the Baath part and religious fundamentalism represented by the Brotherhood. Some Syrians — particularly those from older generations — thus remain wary of the possibility of the Brotherhood’s ruling the country should the embattled Syrian regime collapse.

Baath failure

Indeed, the Syrian Brotherhood has matured since its bloody showdown with the regime in the late 1970s and early 1980s. However, its image has not changed much, leaving some convinced that it would still resort to violent means to impose its vision on society.

The younger generations, in contrast — those not yet born when the Brotherhood confronted the regime — are more inclined to give the group another chance to prove that it has changed. More important perhaps for them is the fact that they want to see some group other than the Baath party ruling the country.

For five decades, Syrians have known no other party in power but the Baath. For them, Baathism has not only failed to answer their political, economic, and social worries, but has also spoiled the spirit and values of Syrian society. It is precisely because the Baath failed that people began searching elsewhere for answers — i.e., political Islam.

Not all Syrians, however, are fond of Islamist parties; indeed, some are not. The very composition of Syrian society would make it extremely difficult for the Brotherhood and other Islamic forces to win a majority in any free and fair elections.

In Syria, nearly 30 per cent of the population comprises of the religious minorities, who would never support an Islamic party. Likewise, Kurds, tribes, and Bedouins, along with other groups within the Sunni majority, would not be attracted by their ideology.

The Kurds would naturally vote for their nationalist parties. Tribes and Bedouins would vote for their local and tribal leaders. Given that these groups together make up a sizable part of voters in any parliamentary elections, the Muslim Brotherhood or sister groups would not be able to take half the seats in any incoming chamber.

This is a key reason why it would be much more difficult for the Syrian Brotherhood to take power than it has been for their fellows in Egypt.

Should the Baath regime collapse in Syria, therefore, the Brotherhood will not automatically replace it. The Islamic group will need to work really hard to reserve a leading place in Syria’s political future.