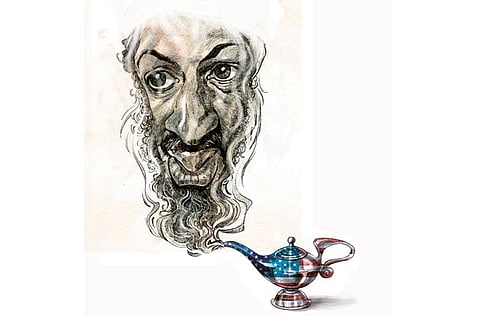

Bin Laden's crude worldview

Adel Safty writes: While Washington exaggerated his significance and reach for political purposes, he revelled in that fame

With the recent announcement by Washington that American special forces had killed Osama Bin Laden, manifestations of celebration broke out at various locations throughout the United States.

This is not surprising given how Bin Laden had been demonised to represent the face of terrorism and to haunt the American psyche with the horrors of September 11. It seems that there is a direct relationship between the perception of the seriousnes of a crime and the appetite for revenge.

President Barack Obama received praise for his handling of the operation and for the strong leadership he had shown in his announcement to the American people that Bin Laden had been located and killed, Obama was measured and showed none of the triumphalism that his predecessor had shown when he prematurely announced that the mission in Iraq had been accomplished.

Obama gave credit to the American people and to American values and recalled the pain of the relatives of the victims of September 11 attacks. He rightly affirmed that the ‘United States is not and never will be at war with Islam'.

But the news of the killing of Bin Laden also led to a debate most curiously characterised by the wrongheadedness of its focus of interest, given the enormity of the threat that Bin Laden had been made to represent to American security.

Some Republicans seized on the occasion to emphasise the importance of giving credit to former president George W. Bush. New York Congressman Peter King, the chair of the Homeland Security Committee, said Bin Laden would not have been found and killed without the use of torture to exact information from prisoners. Congressman Steve King, a Republican of Iowa, suggested that Obama ought now to reconsider his opposition to Bush's torture policy.

The debate is rendered more curiously intriguing with the addition of the obligatory conspiracy theories.

Former deputy assistant secretary of state under three administrations Steve R. Pieczenik says that Bin Laden had died in 2001. He further claimed that a top American general told him directly that the September 11 attack was a false flag attack. Pieczenik also said that he was prepared to testify before a federal grand jury.

Pieczenik said that Obama had prepared this hoax to save his presidency from plummeting approval ratings.

Back on earth, the poverty of the debate that followed the announcement of the killing of Bin Laden is surprising. The fight against Al Qaida and its leader was after all the driving force, after September 11, behind the unprecedented commitment of the US to the so-called global war on terror.

No examination of the war on terror, its costs and its implications for American foreign policy or for America's place in the world. No attempt at re-examining the role the CIA played in aiding and training Bin Laden and his followers when they were fighting the Russians in Afghanistan. Bin Laden was a freedom fighter then; he only became a terrorist when he directed his anger at America and American policies in the Middle East.

Iraq effect

Independent reports calculated that sometime in the Obama presidency the war on terror started by Bush will have cost US taxpayers $1 trillion (Dh3.67 trillion), that's four times more than the cost to the US of fighting the First World War.

To place this in another context, consider the World Bank estimate that it would cost $50 billion a year of additional foreign aid to achieve the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDG) by 2015. (The MDG includes the eradication of extreme poverty, achieving universal primary education, improving maternal health and ensuring environmental sustainability.)

A study of terrorist attacks after the Iraq invasion in 2003, said to be the first to attempt to measure the ‘Iraq effect' on global terrorism, was conducted by the Centre on Law and Security at the New York University Foundation for Mother Jones magazine.

It found that the number killed in jihadist attacks around the world has risen dramatically since the Iraq war began in March 2003. "Our study shows that the Iraq war has generated a stunning increase in the yearly rate of fatal jihadist attacks, amounting to literally hundreds of additional terrorist attacks and civilian lives lost," said the researchers.

There is no escaping the conclusion that the war on terror had become in fact the leading cause of terrorism. But just as Washington exaggerated Bin Laden's significance and his reach for political purposes, Bin Laden revelled in the fame and came to believe in mythology. In an interview with Time magazine in December 1998, he started to refer to himself in the third person and to present himself as if he were larger than life.

This locked him in a vicious circle. The crudity of his worldview and the manichean dicotomy of the battle he claimed to be fighting were the mirror image of Bush's declaration to the world: You are either with us or with the terrorists.

Bin Laden predicted that if he was killed by the Americans, the Muslim world would rise up in arms and carry on the struggle against America. Nothing of the sort happened or is likely to happen. Other than an ill-advised statement from Hamas calling Bin Laden a holy warrior, the Middle East, in the throes of a continuing struggle for democracy, and the Muslim world, is largely indifferent to his death.

In death as in life Bin Laden remains irrelevant. His death removes a famous face from the equation, and somewhat satisfies the instinct for revenge and the hunger for justice.

But it does not solve America's problem with the Muslim world or the Middle East. To do so Washington needs to address the underlying causes of its problematic relationship with the Muslim world, not its symptoms.

Adel Safty is Distinguished Professor Adjunct at the Siberian Academy of Public Administration, Russia. His new book, Might Over Right, is endorsed by Noam Chomsky, and published in England by Garnet, 2009.