Bangladesh’s quest to safeguard its identity

Campaign against Jamaat indicates that the country is returning to the right path

Dhaka was a distant dot on India’s map when I was living in my hometown, Sialkot. Partition pushed me to Delhi and, happily for me, the dot came closer. I took the first plane to Dhaka as soon as it became the capital of the newly-formed Bangladesh. For the first time, I heard Joi Bangla (victory to Bangladesh), a slogan or an invocation, from the weary Bengalis returning home. The airport was littered with luggage and looked disorderly with long queues at immigration desks. Yet every face was writ with determination to make a success of the new country.

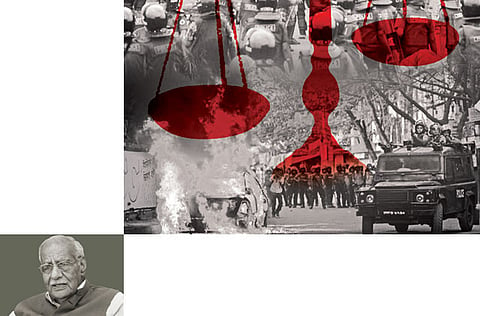

That was nearly 40 years ago. Whenever I go to Dhaka I look for that spirit. Now I find the sense of Joi Bangla returning. Most of the 180 million people proudly find that the idealism in them has not been extinguished. In the three-week-old stir, they have proved that their fight against fundamentalism, something they witnessed when they separated from Pakistan, is still raging. It seems that a country which had lost its ethos is returning to the right path.

That the Jamat-e-Islami should oppose a secular ideology is understandable because the party does not believe in pluralism. Yet its use of violence to deny the country its ideology of independence is to deny the very baptism of the nation. The independence struggle represents the revolt against the colonial rule. Religion doesn’t make nations; nations make religion. It is futile to keep Muslims and Hindus apart on the basis of their beliefs.

People who staked all they had for independence had three basic demands: Death sentence for the perpetrators of war crimes committed during the independence struggle; a ban on the Jamat-e-Islami and its student wing, the Islami Chattar Shivir, and, boycott of companies controlled by the Jamat.

It has taken Bangladesh some years to realise that it cannot sustain its secular as well as nationalist spirit without punishing those who usurped power in the name of independence. But they were not the real freedom fighters. The youth, which must get the credit for leading the independence movement, has forced people to recognise that the real freedom activists were pushed aside when they should have been the real beneficiaries of independence. In the process, the anti-independence activists have seen during the years they were in power that the original commitment to stay pluralistic would be mixed with religion, just as Khaleda Zia’s Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and the Jamaat did.

The youth have made the country realise that those who opposed freedom for Bangladesh and oppressed their own people must be separated from the freedom fighters. The latter see the Jamat as a part of the Razakar militia and are determined to punish those who sided with the aggressors. They consider it essential to remove the stranglehold of the Jamat from politics, economy and society. Make no mistake, these are not the only young people in Bangladesh against communalism, but they seem to be the only ones who count.

The situation is not easy when money is pouring into the coffers of the Jamat and when the only viable opposition BNP, has moved closer to fundamentalists. Against this background, it was natural that Khaleda Zia would cancel her appointment with Indian President Pranab Mukherjee, who was visiting Dhaka. Khaleda may have been sending a message to New Delhi that the campaign against the Jamat was influenced by India. For her, even this far-fetched argument means a lot because elections are only a few months away.

What the two, more so the Jamaat, do not seem to realise is that Bangladesh is fighting for its identity — an identity that inspired it to be free and has forced it now to refurbish the wherewithal of freedom. The more the issue is clouded, the louder will the voices get. The Bangladeshis have awakened.

There is a lesson for India too. Our basic commitment to pluralism and democracy has been mutilated by vote-bank politics, leading to the emergence of communalism, caste and regionalism. We have practically destroyed the pluralistic society that we had built since independence. Can we retrieve pluralism and democracy that our forefathers envisaged in the Constitution and placed before us like a pole star?

Bangladesh looks determined to reclaim the purpose for which it was constituted. In contrast, India thinks it has all the time to hark back to old values as well as ideals of the freedom struggle. Bangladesh means business. India has not yet begun to feel what we have lost.

Kuldip Nayar is a former Indian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom and a former Rajya Sabha member.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox