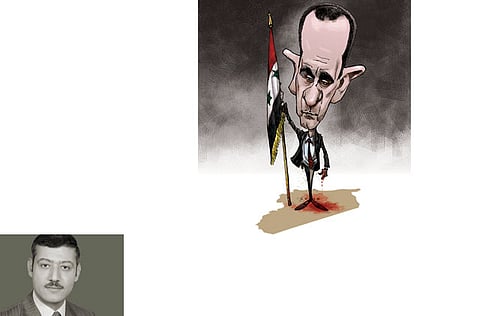

Baath rule widened inequalities in Syria

Al Assad is preoccupied with protecting social and economic interests of the elite

Amongst all the Arab countries that have witnessed social unrest over the past couple of years, Syria has emerged as a unique case. What started as a peaceful social effort to bring about an overdue political reform has turned into a bloody civil war that threatens to engulf the region.

Indeed, the very structure of the Syrian regime, the composition of Syrian society and the geopolitical location of Syria have all dictated the course of the ongoing conflict, yet the quality and nature of leadership is no less important.

Many believe that had President Bashar Al Assad decided, for instance, to embrace rather than confront the demands of the movement for political reform, the Syrian revolution could have certainly taken a different course. Indeed, one should not fail to mention that reform does not come at will, i.e. people do not usually reform because they like to. They are often forced to do so under domestic or external pressures. There was no lack of both in Syria.

When he succeeded his father in July 2000, Al Assad benefited from a long état de grâce. He had no record of corruption or repressive practices. And unlike most of the key figures in his father’s regime, who were in their seventies, Al Assad was relatively young, making him extremely popular amongst his countrymen. Since the young president was also portrayed as moderniser, he was expected to introduce far-reaching reform measures.

No matter what these measures might have been, few expected him to go for full-fledged democracy. Even when domestic and external conditions seemed ripe for change, Al Assad hesitated. His top priority was to preserve the regime he inherited from his father.

Classic dilemma

As soon as he assumed his responsibilities as president, Al Assad faced a classic dilemma with two major questions: How could he start a reform that would respond in a minimal way to the growing demands for political change without undermining the very foundations of his regime? And how could he manage the transition game while precluding the possibility of losing power to more organised social forces — i.e. Islamists.

Al Assad started by allowing a degree of participation sufficient to attract support from groups with an interest in political reform, such as intellectuals and professionals, without, at the same time, creating conditions that might empower these groups or give them the means to undermine the hegemony of the ruling elite. This included giving the media a wider margin of freedom, relaxing restrictions on free speech and allowing what one can call loyal opposition.

Political openness was accompanied by limited economic liberalisation. Its goal was to promote a degree of economic change sufficient to attract foreign investment, reduce debt payments, and create jobs for the young and increasingly educated generations. The challenge was to do all this without undermining the fundamental social and economic interests of the power elite.

Al Assad thought that these strategies would buy him some time to consolidate his power; he quickly discovered however that they had produced the opposite effects. On the political front, intellectual opposition groups — after decades of repression — exploited the limited political openness to challenge the regime. On the economic front, limited liberalisation increased the alienation of social groups traditionally outside the dominant or ruling elites.

Indeed, the economic liberalisation of the past few years and the transition from a state-controlled economy into free market economy has served Syria in many ways but has also created many complications. The ongoing conflict in Syria today can be absolutely defined as a conflict about the even distribution of power and wealth.

The roots of the current conflict can be traced to at least the early 1960s when the Baath party seized power, bringing about fundamental social change. The seizure of power by the Baath party in 1963 brought rural and poor social class into control. In many ways, the Syrian revolution represents the end of an era that has largely been marked by Baath domination of state and society in Syria. The ongoing conflict can be characterised as the revenge of geography and demography in Syria, i.e. rural versus urban, poor vs rich, periphery vs centre and young vs old generation.

Al Assad failed to understand the changing domestic environment and the shift in the social balance of power although he has contributed to this shift in a major way. Instead of helping to bring about smooth transition he chose to resist it by violent means and that has cost him dearly.

Dr Marwan Kabalan is the dean of the Faculty of International Relations and Diplomacy at the University of Kalamoon, Damascus.