On October 18, Saudi Arabia took the world by surprise when it abruptly rejected a UN Security Council seat to which it had just been elected. No member of the UN had ever done such a thing, and the Saudi government’s explanation was similarly stunning.

“The ... double standards existing in the Security Council prevent it from performing its duties and assuming its responsibilities,” the Saudi Foreign Ministry charged, and results have been “continued disruption of peace and security, the expansion of the injustices against peoples, the violation of rights, and the spread of conflicts and wars”.

The statement was even more critical of the recent Security Council resolution that effectively immunised Syrian President Bashar Al Assad from punishment for using chemical weapons against his own people in August: “Allowing the ruling regime in Syria to kill its people and burn them with chemical weapons in front of the entire world and without any deterrent or punishment is clear proof and evidence of the UN Security Council’s inability to perform its duties,” the Saudi statement added.

For many the Saudi move was never intended to fix the Security Council’s ages-old flaws. It was in fact “a message for the US”, as Prince Bandar Bin Sultan, Saudi Arabia’s national security adviser; put it in a conversation with European diplomats, according to Reuters.

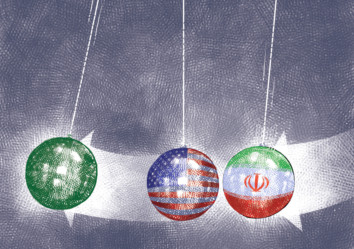

Prince Bandar threatened that relations between Riyadh and Washington, already badly strained over the Obama administration’s policies toward Syria, Egypt, and Iran, are poised to get worse. He reportedly said that his government will scale back its cooperation with US intelligence agencies in assisting the Syrian rebels fighting against Al Assad, and will seek other allies to work with instead. Clearly, Saudi Arabia’s refusal to take its seat on the Security Council had much less to do with the UN than with calling attention to Riyadh’s anger and frustration at how its most important western ally has been acting.

In fact, for a few years now, the US-Arab Gulf allies have been growing more wary about Washington’s policies and intentions in the region. On the one hand, they feel that the US has betrayed them when it failed not only to bring about more stability to the region after the invasion of Iraq, but has also benefited Iran.

Instead of containing and deterring Iran, US policy has in fact contributed to strengthening Tehran’s regional influence and failed to deal with its nuclear ambitions. On the other hand, Arab Gulf states feel that they can no longer rely on the US to ensure their security and well-being. All in all, “no faith in Washington” is the simple answer that one would get from Arab officials in the Gulf when asked about US policy these days.

Most Saudis still bitterly remember the empty US assurances during the disturbing events of the Iranian revolution. In 1979, the Carter administration dispatched several military units to the Gulf. However, the Saudis discovered, the F15 fighter planes, sent to bolster their security after the fall of the Shah, were in fact unarmed. More recently, the Saudis have watched with pain and anger how easy it was for the Obama administration to abandon a major ally, Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak, and side with his enemies, the Muslim Brotherhood.

Indeed, most foreign policy experts in Washington would emphatically admit that the US faces major problems in fixing its relations with its allies in the region in general. There is however a sense of urgency concerning the restoration of the strategic alliance with Saudi Arabia.

They are reasons to believe that for all the talk of US energy independence, as a result of the shale gas revolution, energy experts believe that the US will remain directly dependent on massive energy imports well beyond 2030, and equally dependent on a global economy fuelled by Arab Gulf oil.

The flow of oil, gas, and petroleum exports not only requires the security of key exporting states; it requires the security of regional pipelines and shipping routes. This makes Saudi Arabia national security vital issue for the US.

“The US has valuable relations with Egypt, Israel, and Jordan. Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and Oman all offer key bases and strategic facilities. Only one state, however, has the geographic position, military forces, strategic depth, and common interests to be a key strategic partner in the Gulf. The US needs Saudi Arabia as much as Saudi Arabia needs the US,” Anthony Cordesman, former US National Security Council member and director of the influential Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), argued in a recent study.

Having said that, the Obama administration needs to act fast to allay the fears of its Arab allies before it is too late for assurances to be sufficient tools to restore trust.

Dr Marwan Kabalan is the dean of the Faculty of International Relations and Diplomacy at the University of Kalamoon, Damascus.