The Unites States’ obsession with the threat from Al Qaida urgently needs debunking. It has led national security chiefs and politicians dangerously astray — including President Barack Obama himself.

Traumatised by the terrorist attacks on the American heartland of September 11, 2001, the US launched two catastrophic and unnecessary wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, at great cost to its armed services, its finances and its reputation. That was by no means the full extent of the damage.

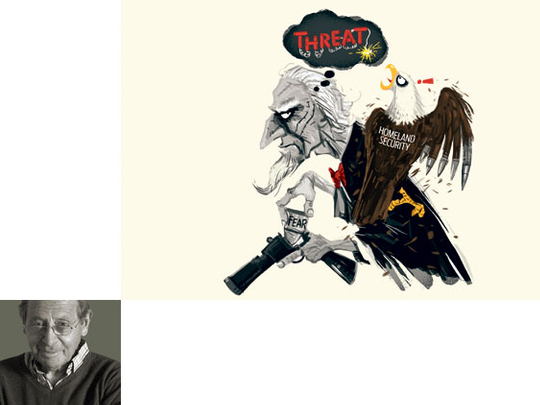

The war on terror also caused the US to create a monstrously-inflated national security-industrial complex, that today employs nearly a million people with high security clearances, seriously eroding America’s precious civil liberties; it caused the CIA to become a para-military organisation as concerned with extra-judicial assassinations as with its traditional intelligence-gathering; and it has driven Obama to rely on missile strikes from unmanned drones which, as well as killing the occasional Islamic fighter, slaughter large numbers of innocent civilians, arousing fierce hostility to the US.

The drone strikes are widely thought to create far more militants than they kill. Barbara Bodine, who served as US ambassador to Yemen from 1997 to 2011, says that drone attacks ‘most assuredly do far more harm than good.’

All these subjects and many more are explored in detail in The rise and Fall of Al Qaeda (Oxford University Press), an important new book by Fawaz Gerges, Professor of Middle East Studies and International Relations at the London School of Economics. It should be required reading in the White House. In an ideal world, his scathing critique of American security policies should get American officials and politicians to change course.

I must declare an interest. I strongly recommend Professor Gerges’s book because he expresses, better than I could have done, many of the ideas which I have put forward in my columns over the years.

His basic argument is that Al Qaida is by no means the strategic, existential threat it is made out to be by the pundits of terrorism. It is a small, weak organisation, with limited tactical aims — ‘more of a security irritant,’ Gerges maintains, ‘than a strategic threat.’ The figures are striking. At the height of its powers in the late 1990s, Al Qaida comprised some 3,000 to 4,000 armed fighters. Today, its ranks have dwindled to 300, if not fewer. In Afghanistan, there is now, for all practical purposes, no Al Qaida. The mistake the US continues to make in Afghanistan is to link the Taliban to Al Qaida, rejecting any separation between them. But they are very different. The Taliban are a local, essentially Pashtun force, dedicated to protecting the country’s tribal and Islamic traditions and ridding it of foreigners. Al Qaida — at least in its heyday — aspired to be a transnational movement.

Yemen is another country where Al Qaida is usually said to pose a major strategic threat. But, as Gerges argues, Al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) — formed by the 2009 merger of the Saudi and Yemeni branches — has no more than between 50 and 300 core operatives, mostly semi-literate rookies with little combat experience.

Yet, a decade after September 11, overreaction is still the hallmark of the US war on terror. Americans and Westerners are fed a constant diet of catastrophic scenarios and scare tactics. The result, Gerges says, is that Americans have internalised an exaggerated fear of terrorism. Obama himself has bought ‘the doomsday scenario offered by his national security team.’ This American overreaction provides the oxygen that sustains Al Qaida.

The fear of terrorism has not only taken hold of the imagination of Americans, it also drives government policy. But all the war on terror really does, Gerges maintains, is legitimise Al Qaida’s failed ideology and expand the worldwide circle of the West’s enemies.

In the Muslim world as a whole — in Iraq, Yemen, Palestine, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and the Maghreb, in Indonesia and elsewhere — Al Qaida now faces a hostile environment with fewer recruits and shelter. Ordinary Muslims join the authorities in chasing Al Qaida away from their neighbourhoods and streets.

AQAP has attempted to carry out a few terrorist acts abroad — such as the attack on the Saudi counter-terrorism chief Prince Mohammad Bin Nayef, the failed underwear bomber, the would-be New York subway bomber, and the foiled Times Square bomber — but its real focus is local. In Yemen, for example, it is attempting to use its tribal connections to gain a foothold in the southern secessionist movement, one of the several rebellions threatening the regime of President Ali Abdallah Saleh. It remains first and foremost a Yemeni problem, one that must be tackled from within.

Gerges cites two incidents among many, which have inflamed Yemeni opinion against Saleh and his American allies. The first he mentions occurred in December 2009 when a US Navy ship off the coast of Yemen fired a double cruise missile, loaded with cluster bombs, at what it thought was an Al Qaida training camp. Instead, the strike killed 41 members of the Haydara family in a Bedouin encampment. In May 2010, a US cruise missile killed Jaber Al Shabwani, deputy governor of Marib province, and four of his escorts. He had reportedly been seeking to persuade the militants to lay down their arms. The killing sent shock waves through the Saleh regime, undermining its legitimacy in the eyes of the tribes and the public at large. Saleh paid blood money to Shabwani’s family to avoid a bloodbath.

Gerges might have added that on Match 17 this year, a US drone killed 40 people in Pakistan, dealing a blow to US Pakistan relations. How many of the 40 victims were innocent civilians? Of all Arabs, Yemenis currently voice the strongest anti-American sentiments. But such incidents also trigger a backlash among scores of disillusioned and frustrated young Muslims, living in Western societies.

Instead of investing in economic development and good governance in Yemen, the US has squandered precious resources combating AQAP. In 2010, for example, the US gave Yemen $250 million (Dh918 million) to fight Al Qaida, but only $42million for development and humanitarian assistance. Clearly, the figures should be reversed.

What is to be done? Plots against western societies will persist, Gerges believes, so long as the US is embroiled in wars in Muslim lands. The root causes of many recent home-grown terror plots lie in the raging conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Somalia and elsewhere.

The longer the US wages war on terrorism in Afghanistan-Pakistan, the more durable the threat. Pakistan’s slide into anarchy will be a far greater catastrophe for American interests and regional stability than the current mess in Afghanistan. There is an urgent need, he writes, to speed up the withdrawal of western, and particularly American boots from Muslim territories.

What other lessons does he recommend? The first is that US policymakers must bring a closure to the war on terror. Second, there must be a concerted effort to debunk the terrorism narrative and break Al Qaida’s hold on the American imagination. And third, the US should stop viewing the Middle East through the terrorism prism, the Israeli prism and the prism of oil.

Patrick Seale is a commentator and author of several books on Middle East affairs — Asad of Syria: The Struggle for the Middle East and Abu Nidal: A Gun for Hire.