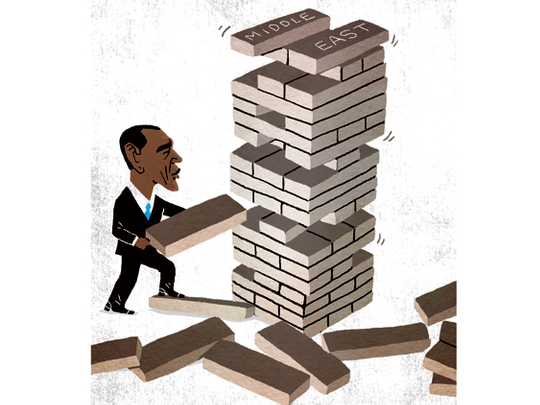

US President Barack Obama’s arrival in the White House raised expectations — often unrealistic — both in the US and abroad. His campaign themes of hope and change were aimed at American voters, but they also spoke to a global public tired of an America whose foreign policy often seemed to consist of little more than swagger and belligerent rhetoric. With hopes that high, the new administration was always bound to disappoint. By now, Obama has learned, as all American presidents do, that settling long-standing conflicts is easier said than done. Middle Easterners have learned that an American president with an unusually international upbringing and the middle name ‘Hussain’ is, still, an American politician.

As he enters his final two-plus years in office — a moment when US presidents traditionally turn to foreign affairs as they seek a lasting legacy — Obama looks out to a Middle East that is both radically different from and frustratingly similar to the one he first encountered as president in 2009. It is a region that offers both the opportunity for great accomplishments and the risk of political disaster.

The most immediate challenge is Iran. It is less than a year since President Hassan Rouhani replaced Mahmoud Ahmedinejad as that country’s leader, but in that time, the momentum of change in the long, difficult relationship between Washington and the Islamic Republic has been breathtaking. In Rouhani, Obama is fortunate to have a counterpart who genuinely seems to want to lower the tensions between the two countries. The bad news is that most of the easy steps have already been taken: Rhetoric has been dialed back, Obama and Rouhani spoke briefly over the telephone last autumn and meetings between the US Secretary of State, John Kerry, and his Iranian counterpart, Mohammad Javid Zarif, are no longer news just because they take place.

The interim agreement Kerry and Zarif negotiated last year concerning Iran’s nuclear programme was a tremendous accomplishment, but it is, as the name states, temporary. A final deal was always going to be much more difficult. It touches on issues of fear and pride on both sides, and faces — also on both sides — opposition from hardliners at home (many of whom still believe the US and Iran should not be talking to each other at all). Difficult as it may be, however, an agreement with Iran feels like a better opportunity for a major Obama administration foreign policy legacy than one between Israel and the Palestinians. One of the enduring puzzlements of Kerry’s tenure as Secretary of State is why he has invested so much of his time, effort and prestige in an attempt to negotiate an Israeli-Palestinian accord that neither side appears eager to reach (at least on terms the other side may ever accept).

Kerry’s decision to suspend his peace efforts earlier this year looks less like an admission of defeat than an acknowledgement of reality. It also recognises that he, like all secretaries of state, works for the president and that as Obama’s time in power grows ever-shorter, the administration’s ultimate legacy will be built on results, not noble-but-doomed efforts — probably the best way to describe American policy in Egypt. Obama began his presidency by trying to nudge Hosni Mubarak towards reform. During the Tahrir Square uprising, he first sought to slow Mubarak’s exit from power, then to speed it up. Later, Washington tried to work with Mohammad Mursi and the Muslim Brotherhood while making it clear that it did not particularly enjoy having to do so. Today, it approaches Mursi’s military-led successors in much the same way. Throughout this process, the common denominator has been an inability to please anyone either at home or in Egypt itself. None of this is the stuff of which legacies are made.

Looming over it all is the continuing conflict that is still George W. Bush’s ‘Global War on Terror’ in all but name. Obama and the people around him clearly believe they are approaching the battle against Al Qaida and its offshoots in a more careful and thoughtful manner than their predecessors, but still fail to understand that the distinction is lost on pretty much everyone outside the administration’s inner circle. Collectively, it is not a pretty picture. Still, two-and-a-half years is a long time and a dispassionate observer will be wrong to write off this administration as a foreign policy failure (as most Republicans and even a few Democrats already do).

Looking ahead, Obama needs to concentrate on what is both achievable and worth achieving. On the (somewhat depressing) list I have just outlined, Iran — though difficult — still seems to offer the best opportunity for success. One may even add that the collective nature of the P5+1 (US, Britain, France, Russia, China + Germany) talks lines up well with his oft-expressed desire to have America lead on security issues, but to do so from within a collective framework. A nuclear agreement with Iran and, perhaps, even an end to the 35-year conflict between the two countries. It will be a big thing and it may — just may — be doable. That, indeed, can be something on which to hang a legacy.

Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches political science at the University of Vermont.