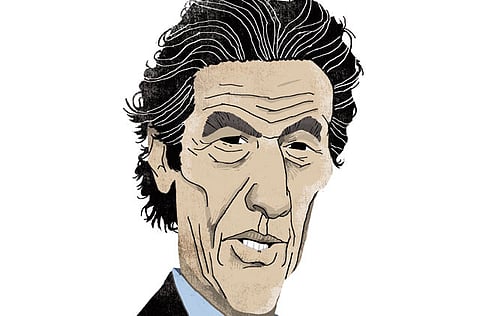

A third political force?

It remains to be seen if Imran can deliver on his commitments

The Chairman of Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) party, Imran Khan, is no stranger to international headlines or controversy. The cricketer par excellence-turned politician’s rise as a credible third force in Pakistan’s strongly divisive two-party dominated politics over the past decade may not have been meteoric, but it is impressive, considering the difficulty of establishing a niche in an arena dominated by Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) and the Pakistan Muslim League Nawaz (PML-N) which have repeatedly failed to meet people’s expectations when given successive chances at the helm.

Whether he is able to sweep the 2013 elections with his political tsunami remains to be seen. Political pundits have dismissed Imran winning no more than two dozen seats in the next election, but they dismiss the power of a strong bloc in parliament that could swing the fate of a coalition government or even build its political standing as a strong opposition force. The earlier euphoric wave of popular support and nation-wide enthusiasm, as witnessed this year when he held significantly large public rallies, may have quietened among criticism of his party expanding to accommodate other breakaway politicians who decided to join the bandwagon, but it has not died down. People are still willing to lay their bets on Imran whose zeal to eradicate corruption and fix the economy is his chief asset, not to forget his past record in philanthropic works. Viewed as a clean politician, Imran’s anti-corruption drive and his practical protestations against Pakistan’s counter-terrorism policy are his chief strengths. Inadvertently, this has also placed an increasing burden on his shoulders with the start of the countdown to elections, scheduled next year.

Ethnically a Pashtun, Imran hails from the Niazi Shermankhel tribe of Mianwali. Born on November 25, 1952, to Ikramullah Khan Niazi, Imran lived in Lahore’s posh Zaman Park, attending the elitist Aitchison College. Having finished his middle school at Aitchison, Imran left for England to study at the Royal Grammar School, Worcester, and then at Keble College, Oxford, where he read for a Bachelors in Politics, Philosophy and Economics and distinguished himself by gaining a place in the Oxford Hall of Fame, a first for a Pakistani or a sportsman. His passion for cricket saw him making his Test debut against England in 1971, marking the start of a brilliant cricketing career which culminated in 1992 when he resigned after leading Pakistan to its first World Cup win. Imran was also awarded Hilal-e-Pakistan, the country’s highest civilian award.

Imran’s charismatic persona, on and off the ground, also earned him the status of an international playboy. But fate had other plans for Khan. His mother’s tragic death from cancer may have been the turning point for Imran, whose attention turned to realising a dream — that of making the charity Shaukat Khanum Memorial Hospital and Research Centre, aimed specifically for free treatment of poor cancer patients.

Imran’s next agenda was to bring about a change in Pakistan’s judicial system, inspired by the need to implement accountability of the country’s elite and politicians. In 1996, he launched his political party, the PTI, which initially drew disdain, most notably pointing at his votebank which at the time only got him — he himself — just one seat in the National Assembly.

His marriage to Jemima Goldsmith, the daughter of Sir James Goldsmith, in 1995 drew criticism at home for marrying a woman of Jewish descent. It also drew unnecessary and unfair flak in the British media that portrayed Jemima living in pathetic conditions back in Pakistan. Unfortunately, the marriage ended in divorce in 2004, owing to Imran’s political activities as per his own admission. Jemima eventually relocated to London with the couple’s two children who regularly visit their father in Islamabad.

Imran’s evolution from international cricketer and “Sexiest Man Alive” to “Taliban Khan” — a label bequeathed by a section of the Pakistani elite for his views in the advent of his political career — to a politician who dared to take the anti-drone campaign to the Waziristan frontier and got consequently labelled as the “slave of the West” by the Taliban on the eve of his recent Peace March against drone strikes — is both colourful and remarkable. He has also authored several books.

More importantly, his achievements are plenty and he has inspired hope among millions across Pakistan that shaping the country’s policies and destiny, in lines with the founding principles, are in their hands. It remains to be seen if he can deliver on the commitments he has made if given a chance.