Putting up a statue used to be a simple affair. Britain fought a battle, and won it, and everyone agreed that it would be a jolly good idea either to celebrate the victors or to remember the fallen. Often, this was done not by a government committee, but by public subscription: What you may call the Big Society at work. To the eyes of posterity, this system has its odd aspects, not least that it delivered statues of rather a lot of generals and admirals whom we do not really remember all that well.

Everyone knows that Nelson stands tall in London’s Trafalgar Square, but who are the fellows around him? I doubt one in 100 people could tell you, but they look very pleasant nonetheless. The statues in Parliament Square, however, are different. These are the elemental icons of British identity — the images that tell you who Britons are as a nation, and what they value.

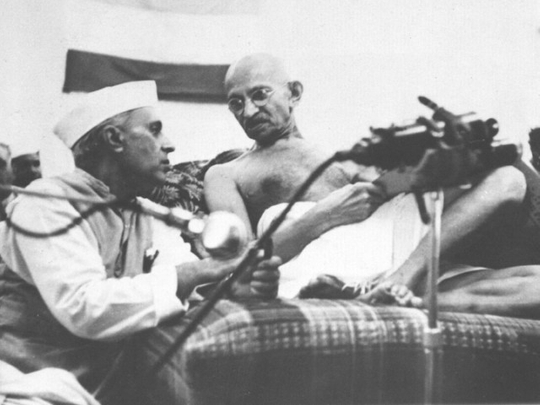

Which is why it is excellent news that Mahatma Gandhi is joining them. The idea is, of course, not without a certain irony. There, the great leader will be — presumably togged out in his loincloth — in the same space as Winston Churchill, who in the 1930s described him as “a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well-known in the East”.

Desperate to keep India in the Empire, Churchill hoped Gandhi would die from a hunger strike in the early 1940s. It was not until after the Indian nationalist leader had been assassinated that Churchill came grudgingly to accept that the fellow had a few positive attributes. In their pushy way, it was the Americans who opened the door to foreign representation. They proposed that Abraham Lincoln join the party, presenting a copy of his famous Chicago statue.

Intended for 1912, to mark a century of peace between the British and the Americans, it did not arrive until 1920, by which time, the two countries had become blood brothers. What with having preserved the Union, abolished slavery and been assassinated, Lincoln still has resonance these days, which is more than can be said for most of the other statues, which are of British prime ministers.

Yes, Benjamin Disraeli is still revered in some quarters as the father of One Nation Conservatism and his epic struggle with Gladstone still has dramatic appeal; First World War buffs and some Welsh and Irish will know of David Lloyd George; Sir Robert Peel is a hero to free-traders and should be venerated by the Metropolitan Police.

However, which children today are taught about Lord Palmerston? Who but historians knows of Lord Derby, whose government passed the 1867 Reform Act and who was the longest-serving Tory leader ever? As for poor George Canning, who was prime minister for a shorter period even than Gordon Brown, all that is remembered of him is that he once fought a duel with Lord Castlereagh.

Perhaps it is emblematic of Britain’s relative decline that the biggest box-office attractions in the square, Churchill excepted, are not from these parts. Of the other three foreigners present, Nelson Mandela would have had the most in common with Gandhi, also having been regarded by a great prime minister as dodgy (even if Margaret Thatcher did become a fan soon afterwards) — and being a symbol of peace and love on a million T-shirts. Mandela’s statue went up in 2007, which, despite his great achievements, was indecently early.

However, New Labour was in power and a Mandela statue was an inexpensive way of climbing on the moral-superiority bandwagon. It was at Churchill’s instigation that, since 1954, Parliament Square has hosted another great South African politician, who means nothing to the crowds of tourists who take selfies with Mandela. Jan Smuts had been a persona non grata with the British establishment when fighting on the enemy’s side in the Boer War and later when negotiating self-government.

But he became a much-admired statesman and member of Churchill’s War Cabinet and in later years, he did ameliorate his enthusiasm for racial segregation. Gandhi’s addition to their ranks is not only welcome in its own right, but a triumph of statecraft. George Osborne, UK’s Chancellor of the Exchequer, explained gravely that the statue would be erected because “as the father of the largest democracy in the world, it’s time for Gandhi to take his place in front of the Mother of Parliaments”.

True. But won’t the Indian government then seem like ingrates if they do not put out the welcome mat to British exporters?

At least, after contentious figures such as Smuts, this is a welcome throwback to the days of enshrining heroes to whom no one could possibly object. As for any vacant spots, as the Chinese market beckons ever more urgently, Osborne may be wise to brush up on his Confucius.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2014