After a decade during which America’s political divide has never been so stark, a resurgence in libertarian demands for smaller government and greater personal freedom is reshaping the US. On the surface, American politics often seems so tribally divided between Democrat and Republican, Liberal and Conservative, that there is little point even bothering with the shades of grey in between.

However, while it is true third-party candidates do not succeed in US general elections, the failures of first the Bush and now the Obama administrations have seen the emergence not of a third party in US politics but a libertarian “third force” that could yet influence the outcome in 2016. Listen carefully and libertarian ideas — with a small ‘l’ — can be heard shaping many of the big issues of the day, from marijuana legalisation to penal reform, from digital privacy issues in the wake of the Edward Snowden revelations to whether the US bombs Syria. What fascinates is how the traditional American yearning for smaller government and greater personal freedom can resonate simultaneously with both conservatives and liberals when those two forces have never appeared more implacably opposed. The Snowden files outraged both liberals on the left and libertarians on the right; the push to legalise marijuana and end the drug war also finds supporters at both ends of the political horseshoe, as do campaigns to change attitudes to gay marriage.

The libertarian sentiment reflects the pitchfork politics that gave rise to the Tea Party on the right and the Occupy movements on the left, both fuelled by public disillusion with the power of conventional politics to deliver anything other than the stagnant status quo. Measuring the potential electoral impact of libertarianism is difficult precisely because it cuts across traditional party lines, which is both its protean strength and political weakness in an era of big-money politics. Put a capital “L” on libertarianism and it largely evaporates — Gary Johnson, the Libertarian Party candidate in 2012, won only one per cent of the popular vote (1.2 million people), but research by the Cato Institute, the libertarian think-thank, points to a much deeper pool of Americans with libertarian leanings. When the institute asked voters if they considered themselves “fiscally conservative and socially liberal — also known as libertarian”, some 44 per cent of Americans were happy to be placed in that category.

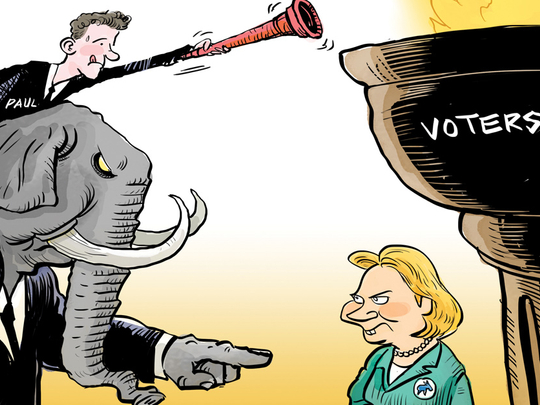

The politician most obviously trying to capitalise on the idea that Americans are not quite so easily pigeonholed into red and blue boxes is Rand Paul, a Republican senator from Kentucky who the bookies rate as a leading contender for 2016. As the son of veteran libertarian Ron Paul, his formula will be to bring libertarian ideas off the fringe — where his cranky dad always languished — and into the mainstream, tapping that well of disaffection that resonates across party lines.

The younger Paul has demonstrated a knack for cutting through when it comes to popular issues — when riot police overstepped the mark in Ferguson, Missouri following the shooting of a black teenager this summer, it was Rand who spoke out about the obscene militarisation of American police forces, hitting a sweet spot with both young liberals and conservatives who are anti-big government types. In the same vein and in a rare moment of bipartisanship, Paul is working with a Democrat colleague to end the mandatory sentencing laws that are clogging up America’s bloated and broken jail system with non-violent offenders, at vast cost and to little good effect.

It is a bold gambit that could find favour both with minorities — particularly African-Americans who are disproportionately sentenced — and the young drug decriminalisation lobby which has gathered strength since Colorado and Washington State legalised marijuana in 2012. To make if off the fringes, of course, Rand must win the Republican nomination, convincing the traditional conservative base of his party to broaden its horizons. “We need to look more like the rest of America,” he told a rally in North Carolina last week — a message greeted, perhaps tellingly, by near silence from the audience. He will also have to show that his isolationist instincts, still popular in a war-weary America but tested by recent events in Iraq and Syria, can sustain a foreign policy that is fit for purpose in the age of Daesh (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant). But were it to happen, a match against Hillary Clinton throws up the intriguing prospect that on some issues — drugs, prisons and foreign policy — a Rand Paul Republican candidacy will be more liberal than that of an establishment Democrat then nearing her 70th year. If his candidacy catches fire, it will be because Paul awakens America’s disaffected centre to the idea that between the battle lines of American politics, beyond the party banners and flags, there is more common ground than is popularly understood.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2014