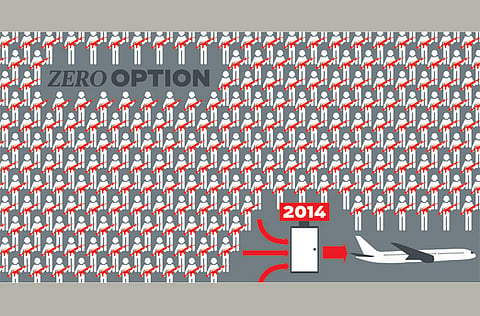

‘Zero option’ the only viable one

Any more than a token presence of US will perpetuate culture of dependency

Last Tuesday, the Obama administration’s spokesperson, Ben Rhodes, announced for the first time that the US may consider a “zero option” that is, pulling all troops out of Afghanistan by the end of 2014. While the administration has insisted that it will not debate troop numbers with Afghan President Hamid Karzai during their meeting yesterday, only the division of “missions and authorities” between the US and Afghanistan, everyone knows that this is a lie. What is really at stake in these meetings is the number of troops and the corresponding political investment that the US will have in Afghanistan’s stability at the end of the formal combat mission.

There is little doubt today that the US is heading for the exits in Afghanistan. In 2009, President Obama committed the US to moving from a combat to a support mission for the Afghan military units by 2014, while drawing down the total number of US troops from the 68,000 currently present. The “US-Afghanistan strategic partnership” commits the US to stay in some capacity until 2024, but it does not specify how many troops will remain or what they will do.

Until recently, the Obama administration was considering a range of options, from drawing down the number of troops by 30,000 by June 2013, to a more gradual drawdown, proposed by General John Allen, which would leave between 6,000-15,000 troops in the country at the end of formal combat operations. Facing enormous budget pressures and rapidly declining public support for the war, the Obama administration has begun to consider even lower numbers, such as 3,000-4,000 troops, or even a pullout of all but its special forces. It has already significantly reduced the number of civilians who will remain in Afghanistan and scaled back its ambitions for reconstruction and aid in the country.

The reaction to the airing of the “zero option” in Afghanistan has been predictable. While it is highly likely that this option is little more than a negotiating ploy, it has drawn out all of those who have a vested interest in preserving an indefinite American role in the country. Thursday, Afghan MPs warned that the US risks a return to civil war if it pulls all of its troops out of the country, and emphasised that training and equipment of the Afghan National Army now underway for 12 years, to little effect must continue apace.

Fred and Kimberly Kagan, both of whom served as advisors to General David Petraeus in Afghanistan and wrote op-eds in favour of the war effort, recently attacked the “zero option” and accused the administration of throwing away everything the US had fought for.

Neoconservative John Bolton has also accused the administration of seeking an excuse for a withdrawal and called plans for a zero option a “guarantee of a Taliban takeover”.

A number of high-ranking former Pentagon officials have also come out against the “zero option”. On January 2, former General Jack Keane blasted the administration for not making withdrawal plans based on “conditions on the ground”.

Last Monday, retired General Stanley McChrystal publicly called for an enduring “security presence” in the country.

All of this suggests that there are strong institutional forces within the Pentagon and among some quarters of the Republican party, that will seek to keep bases and significant military forces in Afghanistan as a way of preventing a civil war and retaining some influence over the Karzai government. The Obama administration should ignore these arguments and keep the “zero option” on the table for three reasons.

First, keeping a sizable number of troops for example, 15,000 troops will do relatively little but provide the Taliban with a rich set of targets. The current US force four times that size is unable to stop the growing violence in the country or halt the Taliban infiltration of military and police units. A much smaller force of 15,000 troops, finding itself under heavy demand by the Afghan military in its struggle against the Taliban, would be no more capable to stop these trends than the current, reasonably well-equipped, US forces.

Unless the US limits the size of its force and the scope of its “support missions”, it will wind up backstopping a corrupt, incompetent and desertion-prone Afghan military in the midst of a civil war, while having fewer logistical and supply resources than it does now. Moreover, unless the issue of legal immunity for US troops in Afghanistan is resolved, there is also the chance that most US forces will be largely confined to bases, especially if they lose some of their logistics assets.

This was the case at the end of the Iraq mission. The key difference with Iraq is that these US bases will be an attractive target amid a civil war. The likely result is that American troops will be hunkered down in bases, awaiting risky support operations in the midst of a civil war, while more and more attacks occur on their doorstep.

Second, it is unclear that retaining a residual force in Afghanistan will convey any of the “influence” that opponents of the “zero option” presume. The presence of a small combat force is unlikely to affect the calculations of Hamid Karzai, who has proven himself to be more-than-willing to engage in conspiracy theories and attack the US, if it conveys a domestic political advantage.

It is a regular trope among Republican circles to argue that military bases convey influence and to point to Iraq — where the US sought military bases, but eventually gave up due to concerns over American soldiers falling under Iraqi jurisdiction — as an example where its departure led to growing authoritarianism and a foreign policy sympathetic to America’s enemies. Yet, these critics never spell out why the mere presence of a token number of US troops is going to significantly influence the decisions of a government with vastly different interests than Washington.

The US-Afghanistan relationship will be shaped by much bigger political and economic forces, especially as the Karzai government decides how to respond to a resurgent Taliban. The presence or absence of a small contingent of US forces is unlikely to have any impact on that relationship.

Third, the presence of US troops, even in a support capacity, will further the culture of dependency that has permitted the worst abuses of the Karzai government to continue. The military has received billions in aid and years of direct combat support and training. The result has not been the creation of a reliable US partner, but rather a military prone to desertions and poor performance. Today, the Afghan government remains unable to field more than one combat brigade out of a total of 23 created since 2001 that can fight on its own.

Moreover, this culture of dependency has sustained a government that stole an election, engaged in blatant corruption and shown signs of increasing brutality. In late 2012, the Karzai government blocked investigations into how friends of the Karzai family turned the Afghan central bank into a Ponzi scheme, and resumed public hangings of Taliban fighters and criminals.

At the same time, Karzai has blamed the US for generating insecurity in Afghanistan and has had the gall to suggest that continuing immunity for US troops after 2014 will be conditional on their ability to provide “peace and stability” for his country. The lesson of the last 12 years is that Karzai can only get away with this because the US so desperately needs him in place in order to justify its counterinsurgency strategy.

All of this suggests that the “zero option” is a serious one: It should stay on the table, if only to provide a wake-up call to the Karzai government. Only by threatening to cut the government of Afghanistan completely loose from US combat and military support and by having it look deep into the abyss, to realise what defeat by the Taliban would really mean will Karzai and his allies have any incentive to get serious about fighting the Taliban and governing the country properly.

Any more than a token presence of US troops will perpetuate this culture of dependency and stop this reckoning from occurring. It would also allow the Karzai government to limp on with its half-hearted war against the Taliban indefinitely, as the Afghan people continue to suffer. If the Afghan government is to survive, it needs to take up its own fight, rather than continually looking over its shoulder for American support, and blaming the American forces when things go wrong.

It is now time for the US to look seriously at the “zero option” and to develop plans for removing all combat troops, except for a small special operations force to target exclusively the 100 or so surviving Al Qaida operatives remaining. However many Americans remain there, the war against the Taliban needs to be President Karzai’s from 2014 onwards and the consequences of failure should be owned by him.

After more than 2,156 US troops killed and 18,109 wounded since 2001 and more than $590 billion (Dh2.17 trillion) given in aid, it is time to call an end to America’s war in Afghanistan. With such losses, it is hard to accept that the US war in Afghanistan will end without a decisive victory, but keeping substantial American troops present in the country indefinitely will confer no real political or strategic advantages while risking death and injury to even more young Americans.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Michael Boyle is assistant professor of political science at La Salle University, Philadelphia.