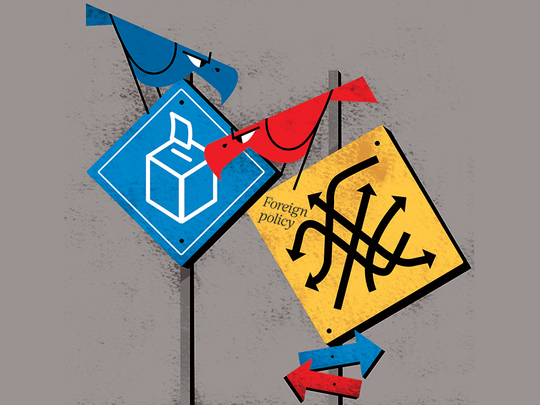

American election campaigns are rarely built around foreign policy. That might or might not be a good thing. On one hand it seems far from crazy to hope for a reasonable discussion of policy differences among people seeking the world’s most powerful elected office. On the other hand, when foreign affairs do get discussed the quality and tone of the debate are rarely edifying.

When Republican presidential hopefuls discuss the Middle East they complain of American weakness, try to out-do each other with promises of military action against Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) and denounce the Iran Nuclear Deal. Democrats promise a more activist American role in Syria, but stop short of the large ground deployments some in the GOP favour.

With the exception of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, all the candidates from both parties pledge loyal support for whatever Israel’s current right-wing government does or will do either at home or beyond its borders.

Those are the headlines, and many people reading this column may now be saying ‘so what else is new?’

Look more closely, however, and — putting the question of Palestine aside — there are hints that a lot may change under the next US president no matter who he or she is.

At a basic level, the obvious contrast is between Hillary Clinton and the others. Hillary represents continuity in foreign policy not only because she was US President Barack Obama’s secretary of state for four years but, perhaps more importantly, because she is the embodiment of mainstream Washington’s foreign-policy thinking — a centrist consensus that does not exist in most other aspects of American political life (on the Republican side Ohio Governor John Kasich also represents this bi-partisan world of foreign policy think tanks and once-and-future government officials. Kasich, however, has virtually no chance of becoming the Republican Party nominee). A Hillary administration may rethink America’s involvement in the Middle East, but it will do so only slowly and in a step-by-step manner. It will be more inclined than Obama to use military force, but it will be a difference of degree rather than a dramatic break with the last eight years.

Sanders as United States president would represent a real change in how things are done in Washington, particularly where Israeli-Palestinian relations are concerned. But barring some sort of spectacular implosion on Hillary’s past, Sanders is not going to be the Democratic Party’s nominee. After last week’s New York State primary, the delegate math is clear: He has virtually no ability to stop Hillary (and despite what you may hear over the coming weeks, Sanders is not going to be Hillary’s pick for vice-president — a cautious politician like Hillary will never put a political outlier like Sanders on her ticket).

That leaves the Republicans. Real estate magnate and reality TV star Donald Trump caused a stir a few weeks ago when he mused about a number of countries, including Saudi Arabia, possibly coming to possess nuclear weapons under a Trump presidency. He has talked alternately about keeping America as far away from the Middle East as possible and of re-invading Iraq to seize the country’s oil fields. He says he plans to demand that America’s Gulf allies pay for the US military presence in the region. His policies, such as they are, appear to be predicated on the belief that America’s military and economic might allow it to demand — and get — whatever it wants from friends and foes alike on whatever terms it chooses (how this squares with Trump’s equally oft-asserted claim that America is fatally weak and respected by no one, he does not explain).

Trump’s only remaining serious opponent, Senator Ted Cruz of Texas, offers a Middle East policy that can neatly be summed up as: “Carpet-bomb” Daesh, tear up the Iran agreement and always support Israel.

Put another way: Neither man appears to have given very much thought to either foreign policy or the Middle East. Cruz says whatever the tactics of the moment seem to require. Trump pretty much makes it up as he goes along.

What none of this takes into account, however, is the mood of America. That Sanders, Cruz and, especially, Trump have built their campaigns around Americans’ anger and frustration is hardly news. What is important to understand is that this goes far beyond the role of money in American politics or a feeling that everything in Washington is rigged on behalf of America’s donor class. It extends to foreign policy in general and to the Middle East in particular. It was embodied in the CNN reporter who, asking Obama about Daesh at a recent news conference, said “Why can’t we just get the [expletive]?”

The question is, when all of this is going to reach critical mass? Neither Trump nor Cruz is invested in the received ways of Washington. Both, as president, will likely be happy to treat long-held, and often successful, policies aimed at regional stability as money to be saved and another field to be ‘shaken up’.

But even under a Hillary administration, some shake-up may occur if the mood in America makes it hard for the next president to do anything else. An election that has produced so many surprises seems likely to produce still more.

Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches Political Science at the University of Vermont.