Will Tehran cease and desist?

Iran is now a colonial power that aims to rule Arab world and that objective is facilitated by global powers

Though intensely unpopular throughout the Arab world, Iranian leaders pretend that meddling in Arab affairs and, worse, attempting to change the course of history, is their divine right. As a major regional power that embarked on yet another revolution in 1979 — which followed an earlier effort in 1905-1911, a coup in 1953 and a bona fide dictatorial regime that was replaced by an equally tyrannical one — Iran has espoused totalitarianism with gusto. Its supremacist ideology, which Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini and his successors sought to export, required hegemony though there were few takers in the immediate neighbourhood. Against the tide of lukewarm reception that seldom penetrated Sunni constituencies, Tehran adopted violent methods whose aim was to support its extremist ideology, especially since the regime banked on a hardline political interpretation of Islam. Will Tehran succeed in imposing its hegemony?

Persia, once a great nation that fought the Greeks, Romans, Turks, Mongols and others, was conquered by Islam in the seventh century (637–651) as the Zoroastrian Sasanids were tamed by emancipated but determined Abbasids. Remarkably, conversion from Sunnism to Shiism occurred much later, stretching between the 16th through the 18th centuries when the Safavids who, it is worth remembering ruled the country, rekindled Persian cultural supremacy as a defining feature of society.

Khomeini, who was a visionary ruler, certainly believed that Iran could, once again, be a world power, which is why his successors are determined to acquire a nuclear arsenal and impose their hegemony over the Arab and Muslim worlds. Regrettably, amateur geo-strategists in Washington and Moscow who attempt to differentiate between extremists and others, fail to notice that the vast majority of Iranians insist the country’s “sovereign right to use its technological know-how to acquire the same weapons” as others, including the United States, Russia, China, France, Britain, Israel, India and Pakistan. That is also why most support the regime even if opposition on tangential concerns preoccupies some. In other words, Iranians may differ amongst each other on many issues, though they are all united on the supremacist objective.

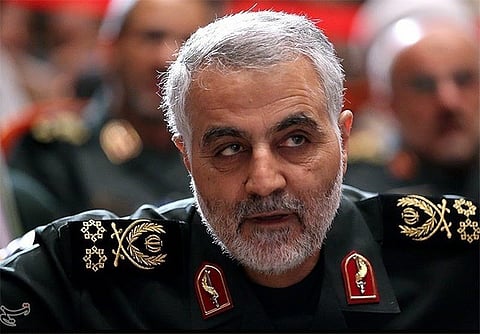

This is the context in which one must assess Iranian interventions from Mauritania to Indonesia and from Morocco to Bahrain, even if Qasim Sulaimani, the Commander of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, Quds Force — who is a frequent-flyer by any stretch of the imagination and who amasses air miles from Moscow to Aleppo — concentrates his efforts on Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen.

Sulaimani deployed his infamous militia alongside the Nouri Al Maliki and Bashar Al Assad regimes in Iraq and Syria, respectively, and Ali Riza Zakani, a member of the Iranian Majlis, declared in late 2014 that “three Arab capitals [Baghdad, Beirut and Damascus], have already fallen into Iran’s hands and belong to the Iranian Islamic Revolution”. Zakani, not renowned for his modest views, recorded that Sana’a became the fourth Arab capital to join the Iranian Revolution after Al Houthi rebels overthrew its legitimate president.

More recently, Tehran boasted that the Yemeni Ansar Allah [Supporters of God] movement, its designation for Al Houthis, rejected the United Nations peace plan that was negotiated in Kuwait because it allegedly could not unite the war-torn country. Few took notice though the unceremonious dismissal of the peace proposal, which took months of intense discussions under Esmail Ould Shaikh Ahmad, was a slap in the face of the UN special envoy for Yemen. It also telegraphed how Iran intended to control the process since it invented a fresh requirement to proceed — consensual executive authority, including a new president and government, both of which necessitated the accord of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh — which was unlikely to occur. It did not matter one bit that about 10,000 Yemenis have been killed since the conflict began in late 2014.

In Iraq, Prime Minister Haidar Al Abadi remained under strong Iranian pressure, which translated into weakness and indecision at a time when Baghdad confronted serious challenges. Coerced by Sulaimani, Al Abadi moved into the Battle for Fallujah, in what was the near-total destruction of a predominantly Sunni city in Anbar Province. This was no mere liberation of an Iraqi city, where disenfranchised Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) units were entrenched. It was, to put it bluntly, a deliberate refocus away from Mosul, the presumed Daesh capital.

In fact, Iran’s political calculations managed Iraqi civilian leaders in Baghdad so well that Shiite protesters loyal to Moqtada Al Sadr took matters in their own hands. The latter’s militia ransacked the parliament building allegedly because Al Abadi was too slow to introduce reforms but, in reality, because Iran wished to control how the fight against extremists was fought.

In the event, the long-stalled Mosul operation remained in the distant future though Tehran exacerbated sectarian tensions because Sulaimani instructed Al Abadi to never contemplate a government with a Sunni presence in it. Fallujah confirmed that what Iran wanted in Iraq was to further divide Arabs along Sunni and Shiite lines, precisely to create a polarised environment that advanced its hegemonic agenda. Al Abadi probably saw it coming, but his unwillingness or inability to deal with the Shiite “Popular Mobilisation Forces” militia, reinforced Iran’s extremism, though mercifully he did not pose for photographs alongside Sulaimani when the latter congratulated Shiite militias who “liberated” Fallujah.

Iran’s premier militia, Hezbollah, has followed specific orders to promote the Iranian agenda in Lebanon too, even if its involvement in the bloody Syrian Civil War derailed some of political objectives that both sides pursued. Still, and no matter how unpalatable Hezbollah’s internal shenanigans appeared to be, the party succeeded on imposing a leadership stalemate simply because Iran was not ready to abandon its Shiite Crescent vision that stretched from the Gulf to the Mediterranean. Tehran prefers a political void in Lebanon, which allows it to manipulate various local actors, instead of dealing with a legitimate head-of-state who, presumably, would place Lebanese interests above Iranian ones.

Iran is now a colonial power that aims to rule over the Arab World. That objective is facilitated by global powers, including the US and Russia — both of which perceive Sunni Islam as a source of threat and wish to apply divide-and-rule planks to weaken the Muslim World. Whether Tehran will manage to impose itself is, of course, a different matter, though few ought to be surprised when hegemony crashes.

Dr Joseph A. Kechichian is the author of the just published From Alliance to Union: Challenges Facing Gulf Cooperation Council States in the Twenty-First Century (Sussex: 2016).