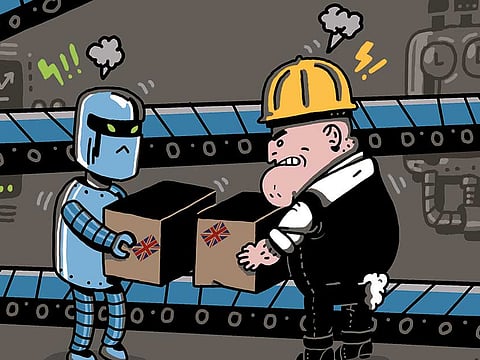

Will robots replace workers in the near future?

Those in wholesale and retail sectors in the UK are at highest risk from breakthroughs in robotics

Millions of workers are at high risk of being replaced by robots within 15 years as the automation of routine tasks gathers pace in a new machine age. A report by the consultancy firm PwC found that 30 per cent of jobs in Britain were potentially under threat from breakthroughs in artificial intelligence (AI). In some sectors, half the jobs could go. The report predicted that automation would boost productivity and create fresh job opportunities, but it said action was needed to prevent the widening of inequality that would result from robots increasingly being used for low-skill tasks.

PwC said 2.25 million jobs were at high risk in wholesale and retailing — the sector that employs most people in the United Kingdom — and 1.2 million were under threat in manufacturing, 1.1 million in administrative and support services and 950,000 in transport and storage. The report said the biggest impact would be on workers who had left school with General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) or lower, and that there was an argument for government intervention in education, life-long learning and job matching to ensure the potential gains from automation were not concentrated in too few hands.

Some form of universal basic income might also be considered. Jon Andrews, the head of technology and investments at PwC, said: “There’s no doubt that AI and robotics will rebalance what jobs look like in the future, and that some are more susceptible than others. “What’s important is making sure that the potential gains from automation are shared more widely across society and no one gets left behind. Responsible employers need to ensure they encourage flexibility and adaptability in their people so we are all ready for the change. “In the future, knowledge will be a commodity so we need to shift our thinking on how we skill and upskill future generations. Creative and critical thinking will be highly valued, as will emotional intelligence.”

Education and health and social care were the two sectors seen as least threatened by robots because of the high proportion of tasks seen as hard to automate. Because women tend to work in sectors that require a higher level of education and social skills, PwC said they would be less in jeopardy of losing their jobs than men, who were more likely to work in sectors such as manufacturing and transportation. Thirty-five per cent of male jobs were identified as being at high risk against 26 per cent of female jobs. The PwC study is the latest to assess the potential for job losses and heightened inequality from AI. Robert Schiller, a Nobel-prize winning US economist, has said the scale of the workplace transformation set to take place in the coming decades should lead to consideration of a “robot tax” to support those machines make redundant.

John Hawksworth, PwC’s chief economist, said: “A key driver of our industry-level estimates is the fact that manual and routine tasks are more susceptible to automation, while social skills are relatively less automatable. That said, no industry is entirely immune from future advances in robotics and AI.

“Automating more manual and repetitive tasks will eliminate some existing jobs but could also enable some workers to focus on higher value, more rewarding and creative work, removing the monotony from our day jobs. By boosting productivity — a key UK weakness over the past decade — and so generating wealth, advances in robotics and AI should also create additional jobs in less automatable parts of the economy as this extra wealth is spent or invested.”

He added that the UK employment rate of just under 75 per cent was at its highest level since modern records began in 1971, suggesting that advances in digital and other labour-saving technologies had been accompanied by job creation. He said it was not clear that the future would be different from the past in terms of how automation would affect overall employment rates. The fact that it was technically possible to replace a worker with a robot did not mean it was economically attractive to do so and would depend on the relative cost and productivity of machines compared with humans, Hawksworth said.

PwC expects this balance to shift in favour of robots as they become cheaper to produce over the coming decades.

“In addition, legal and regulatory hurdles, organisational inertia and legacy systems will slow down the shift towards AI and robotics even where this becomes technically and economically feasible. And this may not be a bad thing if it gives existing workers and businesses more time to adapt to this brave new world,” he said.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Larry Elliott is the Guardian’s economics editor and has been with the paper since 1988.