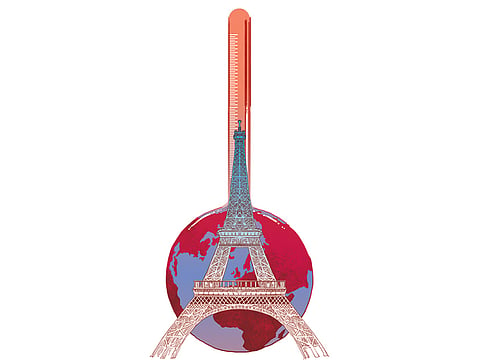

Why Paris was better than expected

Rather than viewing the agreement as the end of the process, it must be seen as a very important stepping stone in a longer process that governments and legislators must now make

Welcome back to the Gulf News Debate. This month the topic of discussion is the significance of the Paris climate change deal and whether it is enough to stave off a global catastrophe. Here we argue why it is indeed enough. However, click on the link for the contrasting view: Falling short on climate in Paris

After years of painstaking negotiations, the climate change deal agreed by ministers from more than 190 countries on Saturday was a diplomatic success. It represents a welcome shot in the arm for attempts to tackle global warming and, crucially, a new post-Kyoto framework has been put in place.

After years of negotiations that proceeded at what the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has called a “snail’s pace”, the more-ambitious-than-expected deal will see greenhouse gas emissions peak “as soon as possible” and achieve a balance between sources and sinks of greenhouse gases in the second half of this century, with progress reviewed every five years.

To help enable this transition, some $100 billion (Dh367.8 billion) a year in climate finance will be provided for developing countries by 2020, with a commitment to further money in the future. Critics of the deal, from different parts of the political spectrum, have already sought to diminish its significance. However, the agreement deserves to be defended robustly, for as United States President Barack Obama has asserted, it may prove to be “the best chance we have to save the planet we have”.

For those who argue that it is not ambitious enough, it needs to be remembered that the long-running talks nearly collapsed several times over the years and that this has been one of the most complex set of international negotiations ever. Whereas the 1997 Kyoto Protocol involved a deal for the European Union states and 37 developed countries, Paris involved developing countries too and thus a much wider range of difficult issues to contend with. Indeed, part of the deal’s importance is that it represents the first genuinely global treaty to tackle climate change.

While the agreement is by no means perfect, it has kept the process ‘alive’, the importance of which cannot potentially be underestimated. Moreover, the once-every-five-years review framework means that countries can toughen their response to climate change in the future, especially if the political and public will to tackle the problem increases with time. So, rather than viewing the Paris agreement as the end of the process, it must be seen as a very important stepping stone in a longer process that governments and legislators must now make. This journey is only possible now because the talks did not collapse and we now have a post-Kyoto framework in place.

Other critics of the deal, including sceptics of climate change, have also lambasted the agreement. Despite the now-overwhelming scientific evidence about the risks of global warming, a number of people, including several candidates for the Republican US presidential nomination, persist with the belief that climate change is at worst a grand hoax, or at best an unwelcome distraction from other key issues.

While there is always uncertainty with science, these critics are misguided. Even if, remarkably, it turns out that most of the scientists in the world are wrong about global warming, what the Paris deal will help achieve is moving more swiftly to remove our dependence on fossil fuels, making the world a cleaner, less polluted and more sustainable place. Moreover, many countries will also develop a broader range of energies, especially renewables, which can help enhance energy sovereignty too at a time of potentially growing geopolitical turbulence.

Alternatively, the consequences of a failure to act now, as climate sceptics seem to advocate, would be the growing likelihood of devastating environmental damage to the planet. As many scientists argue, this is folly on a global scale.

So, despite what critics assert, the Paris deal is a good one that tops off a series of summits in 2015 in what has been called a once-in-a-generation opportunity to build a new international framework to address the challenges of global warming and sustainable development more broadly. For Paris follows not only the UN summit in New York in September, which agreed the new 2030 development goals; but also the finance for development conference in Addis Ababa in July, and the new framework for disaster risk reduction agreed in Sendai in March. Collectively, these agreements could provide a foundation stone for global sustainable development for billions across the world in the coming decades.

Regarding Paris, what is now important is that the political ‘window of opportunity’ provided by the conference is now followed up by governments. From 2016 onwards, implementation will be most effective through national laws as the country ‘commitments’ put forward in Paris will be more credible — and durable beyond the next set of national elections — if they are backed up by national legislation.

These domestic legal frameworks are crucial building blocks to measure, report, verify and manage greenhouse gas emissions. And the ambition must be that they are ratcheted up in coming years so that the intent in Paris is realised to pursue efforts to limit global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius and “well below” 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels — the level scientists say we must not breach if we are to avoid the worst risks of global warming.

This is a very ambitious agenda that will require comprehensive and swift actions from governments if it is to be achieved. While this is uncertain, the fact remains that the Paris deal has created a window for it potentially to happen and what is now needed are well informed lawmakers from across the political spectrum to help ensure effective implementation and hold governments to account so that Paris truly delivers.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS (the Centre for International Affairs, Diplomacy and Strategy) at the London School of Economics.