Why our education system can’t keep up with artificial intelligence

By 2035, humans will be faced with a stark choice: Designer babies or brain implants to modify our knowledge

It’s not a wave, it’s a tsunami. In less than five years, artificial intelligence — AI, as it’s commonly known — has gone from the stuff of science fiction to the forefront of the news, from scientific journals to the strategic plans of the world’s biggest companies.

For Laurent Alexandre, surgeon, graduate of France’s National School of Administration (ENA), entrepreneur, futurologist and author of the recent book La Guerre des intelligences (The War of Intelligences), this isn’t just a trend. It’s a coming sea change, one that will disrupt entire parts of our lives by competing with what, until now, was seen as a fundamentally human characteristic: Our intelligence.

At the same time, he acknowledges that AI — at least for now — is “still utterly unintelligent”. Recognising a cat in a picture, a sentence dictated to a smartphone or even a tumour in MRI images is an impressive feat. But this prowess is still limited to very specific uses, Alexandre argues.

The real novelty that deep learning had promised to bring about, the futurologist explains, is that machines have now started to learn. “From now on, computers are teaching themselves more than they are programming themselves. And this would make the determined and committed students look like apathetic dunces in comparison,” Alexandre writes in his book.

It will be years, probably even decades, before artificial intelligence approaches the level of versatility of our brain. AI researchers are themselves divided over when this will become possible. Alexandre doesn’t see this happening before 2030. Until then, he expects that AI “will quickly compete with radiologists, but, paradoxically, it won’t be able to compete with a general practitioner”. This might be reassuring, but it won’t last.

The core of Alexandre’s book focuses on the next stage, the one where the intelligence of machines will be able to compete with ours. The impacts will be huge on medicine, work, the economy, but also on the sovereignty of our old European countries, which are being incredibly naive in the face of the technological steamrollers from China and the US “They have the GAFA,” he writes in reference to the tech giants Google, Apple, Facebook and Amazon. “We have the CNIL (France’s National Commission on Informatics and Liberty).”

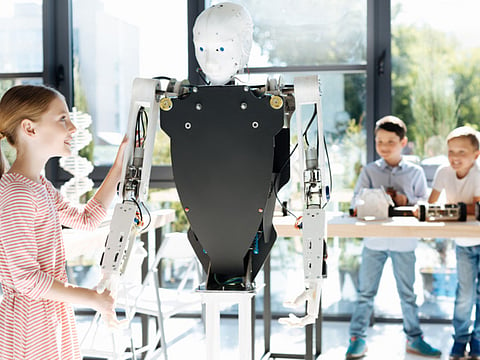

The author examines and denounces, more than he shares, the transhumanist plans of California-based billionaires. And he reckons that we urgently need to adapt our vision for education to the world these people are preparing for us. School, he says, is a “human machine” for manufacturing intelligence. But over the past century it hasn’t evolved, or at least not very much. Tablets and coding have timidly entered the classroom, but the model hasn’t changed. “Education looks like 1950s medicine: Based on the intuition of pedagogues without any sort of scientific validation.”

The charge is brutal, especially against the French system, which has proved incapable of reducing intellectual inequalities. But it’s a problem that will ultimately affect all countries. “Computing giants will produce industrial brains that will be cheaper than those manufactured ‘traditionally’ by the ministries of education. What’s more, these biological brains evolve little, while the power of AI grows endlessly.”

Our response must be to adapt education methods based on the progress made by neuroscience. This isn’t about teaching everybody how to code, an idea that’s become trendy but that Alexandre considers “absurd,” the equivalent, he writes, of imagining in 1895 that all students would become electricians. Instead, we ought to use genetics and AI to personalise teaching, in the same way they already help find tailored treatments for cancer patients, the futurologist argues.

Such a vision might shock, but it’s nothing compared to what comes next. Because the following stage seems to come straight out of a sci-fi movie. Alexandre predicts that by 2035, “Human beings, if they want to keep up, will be faced with two, non-exclusive choices: biological eugenics or electronic neuroaugmentation.” In other words, a “Gattaca”-like scenario in which embryos are selected and improved to produce babies with super IQs. Either that, or something along the lines of Total Recall, where brain implants modify our knowledge.

Are we fated to choose between these two options? Should we believe the author when he predicts that “the schools of tomorrow will be transhumanist or won’t exist at all”? Alexandre knows very well how to use as his basis the most disruptive statements from transhumanist gurus to explain that the future being prepared for us is as frightening as it is inevitable. But doubt should also be allowed, and Alexandre sometimes seems to do that himself.

The book closes with a very instructive afterword in the form of a “Letter to My Children”. In it, the author enjoins his children not to become surgeons or ENA graduates, and leaves it to them to write the end of the story. “Your generation will be the one to shape the contours of this powerful and almost immortal human 2.0 that Silicon Valley, and especially the directors of Google, are longing for,” he writes. “Be strong enough not to let yourselves be deceived by deadly utopias, no matter how nice they look.

— Worldcrunch, in partnership with Les Echos/New York Times News Service

Benoit Georges is Head of Ideas and Debate Department at Les Echos, the French financial newspaper.