The slow rollback of South America’s “pink tide” is laying bare the endemic corruption that was hidden beneath the economic success once enjoyed by the region’s progressive governments. Voted out in democratic elections in Argentina, expelled by what almost conclusively looks like a palace coup in Brazil or tottering on the brink of social meltdown in Venezuela , a league of like-minded progressive presidents has been broken apart in the space of six months.

The ingrained habit of palm-greasing across the continent has suddenly erupted from below the surface, leading to wide-ranging court investigations, especially in Brazil and Argentina, that seem to be shaking the foundations of the social conquests made by the left-leaning politicians now in retreat around the continent. Forged by decades of opposition against an entrenched economic elite they imagined to have finally toppled, the region’s progressive leaders are now seeing that old rival — a right-leaning and mostly white patriarchy — march triumphantly back into office.

At stake is the survival of the badly needed welfare benefits put in place during their administrations, either because they contradict the free-market policies of the new incumbents or because the painful end of the commodities boom that once propped them up has rendered them unsustainable. Although it is a continent-wide swing, there is an especially strong sense of deja vu in the recent and almost synchronous move to the right in Brazil and Argentina, welded at the waist as the two South American giants are by their interlocking economies. Both countries endured lengthy military dictatorships in the 1960s and 70s.

They then made an almost parallel transition to democracy in the 1980s. In the 1990s, they both veered right to launch free-market economic programmes that reduced their dizzying inflation rates for a period, a success that ultimately proved hollow. By the turn of the century, a new bout of spiralling prices and maxi-devaluations crippled both economies once again. Then in 2003, disenchanted with their failed dalliance with liberal economics, both turned left, voting in charismatic leaders with a populist bent who quickly delivered on their promise of a new economic deal that empowered the working class instead of continuing to fatten the traditional upper crust. Brazil’s Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva and Argentina’s Nestor Kirchner saw their region’s exports to China skyrocket during their terms, creating a favourable economic wind that allowed them to reduce their dependence on foreign credit, lifting millions out of poverty while they turned a cold shoulder to Washington, attributing to the US imperial intentions rather than neighbourly feelings.

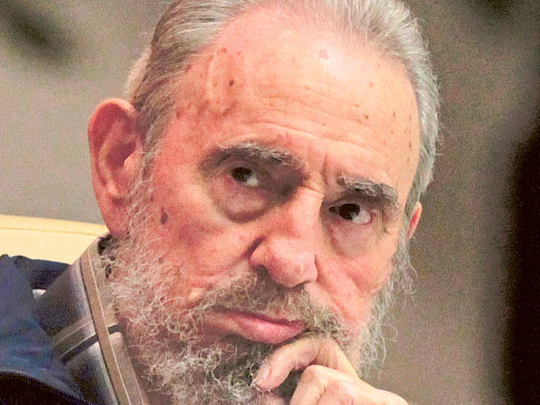

They were soon standing side by side instead with Venezuela’s anti-US Hugo Chavez , awash in petrodollars that he generously spread around to bankroll his dream of a “Bolivarian revolution”, and with Cuba’s Fidel Castro , honorary figurehead of the left-leaning alliance. For a moment, Lula and Nestor, universally known at home by their first names, backed by Chavez, seemed to put South America on the brink of a bright socialist dawn. For the many South Americans who voted them into office, it was a heady experience that was in tune with the 1970s dream of “liberation”, cruelly drowned in blood by the continent’s murderous generals. But, unlike those failed utopias, the new “pink tide” really did reduce the region’s hated foreign economic dependence and seemed to mercifully end the long dominance of local elites.

When three women cast from the same ideological mould, Cristina Fernandez in Argentina, Dilma Rousseff in Brazil and Michelle Bachelet in Chile, followed as South America’s first elected female presidents, the dream seemed complete. Complete, yet unrealistic, an ironic observer might add. But is that true? The wave of populist governments failed to manage wisely the commodities windfall they enjoyed. They did not diversify their economies or stack up reserves to weather the inevitable crash. But the condition of their economies upon leaving office, with the cataclysmic exception of Venezuela, is nowhere near the state of economic chaos left behind by the region’s disastrous free-market experiments of the 1990s. In Bolivia, Evo Morales, the country’s first indigenous president, has proved that socio-economic reforms that reduce inequality don’t always crush the economy.

The populist governments also ushered in a series of forward-looking reforms: gay marriage rights in four countries, including Brazil and Argentina; abortion and the legalisation of marijuana in Uruguay, where Tabare Vazquez of the progressive Frente Amplio (Broad Front) party was reelected only last year. Nestor Kirchner and his wife, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner, who succeeded him in office, may very well be remembered as much by the scale of their corruption as for their social programmes. But the witch-hunt against their wrongdoing currently under way in Argentina’s courts entirely misses the elephant in the room — the uncomfortable fact that Argentina’s entire political establishment is rotten to the core, from left to right and back again.

Almost as if to prove the point, Argentina’s new centre-right president, Mauricio Macri, had barely assumed office when his name popped up in the files of the international Panama Papers financial scandal. The same applies to Brazil. The revelations brought to light by the Lava Jato (Car Wash) investigation suggest a scale of corruption so epic it makes even the Kirchners pale by comparison. But the recent right-leaning “soft coup” that unseated Rousseff was perpetrated by legislators who for the largest part were at the receiving end of that corruption. About 60 per cent of the 594 members of Brazil’s Congress face charges ranging from bribery to homicide.

And wiretaps revealed by the press this week strongly suggest that Rousseff was ousted not as part of any anti-graft crusade, but precisely to squash the investigation into Brazil’s mind-boggling corruption, an investigation that Rousseff did not attempt to block. In the end, South America’s progressive alliance crumbled not because it was ideologically unsound, but because it was built on the same feet of clay as its conservative nemesis. Corruption is a trait sadly common across the region’s entire political spectrum.

—Guardian News & Media Ltd

Uki Goñi is the author of The Real Odessa, published by Granta Books, on the post-war escape of Nazi criminals from Europe.