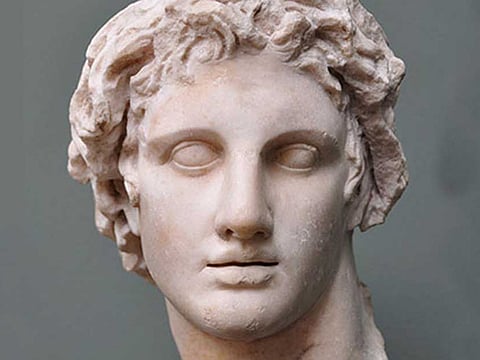

Who was Alexander the Great?

Macedonia is a successor state of the former Yugoslavia and, according to the Greeks, has nothing to do with the ancient kingdom

Alexander the Great was the first global celebrity: A hero, a superman and, so he believed, a god. Not only did he rule most of the known world at the time of his death in 323 BC, he also became a model of paranoid absolutism for all the Caesars and Kaisers and czars to come.

Millenniums later, two nations — Greece and the neighbouring Republic of Macedonia — are locked in a heated dispute over his inheritance. The temperature fell a few degrees late last month when Greek Foreign Minister Nikos Kotzias and his Macedonian counterpart Nikola Poposki forged an entente in the interests of “trust building”. But it has merely dropped from a boil to a simmer.

Alexander was born in Pella, capital of Macedon. Given his birthplace, Macedonians claim Alexander as a founding father. Greece, which has its own northern province of Macedonia, argues that the “M-word” in its Balkan neighbour’s name amounts to a form of identity theft or cultural kleptomania. The modern republic is a successor state of the former Yugoslavia and, according to the Greeks, has nothing to do with the ancient kingdom.

The Greek case, as explained to me by a Greek government official, is this: “Aristotle taught Alexander the Great, and they were both Greek. They would shiver in their graves today at the idea that (Slavs) who migrated to the vicinity of their region seven centuries after them, belonging to a completely different civilisation, would try to change history in order to give allure to their own culture.”

It is indeed unlikely that Alexander the Great set foot in the territory of today’s Republic of Macedonia. And yet he has become, by sheer force of assertion, the country’s mascot. In early spring this year, I visited Skopje, the capital, landing at the conspicuously named Alexander the Great International Airport. In the arrivals hall, I encountered the first of many equestrian statues of Alexander, before driving into town on the (no prizes for guessing) Alexander the Great Highway.

At the pedestrian centre, Alexander, rendered once again on his favourite steed Bucephalus, rears up on an imitation Roman victory column surrounded by Macedonian infantry with their distinctive long pikes, or sarissas. Farther along the thoroughfare, Alexander’s father, Philip II, stands on his own soaring column with fist raised in a power salute. There is even a bizarre nativity scene in which a young Alexander is suckled at the breast of his mother, Olympias, as well as a sculptural tableau of mother, father and world-conquering son.

The Greeks, not surprisingly, are nettled by this thrusting historical symbolism. But their position is not nearly as sound as it may seem; it is in fact a little odd to claim Alexander was exclusively Greek.

Certainly, both Alexander’s birthplaces, Pella and Vergina, the site of Philip’s tomb, lie within the borders of modern Greece. Ancient Macedon, however, extended in Alexander’s time far beyond those borders to encompass part of today’s Republic of Macedonia, an even larger area of the Balkans and, ultimately, most of western Asia.

Alexander was thoroughly schooled, thanks in part to Aristotle, in the Greek mytho-poetic tradition, and it is said that he slept with a copy of Homer’s Iliad beneath his pillow. Yet, he seems to have spoken an indigenous oral Macedonian language, which produced no literature, as well as Greek.

International quarrel

Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BC, was convinced “that these Macedonians ... are Hellenes as they themselves say”. But his phrasing suggests a lively debate, perhaps even a controversy, into which he was pitching. Indeed, ancient sources distinguish time and time again between Greek and Macedonian soldiers.

And as the Oxford classicist Robin Lane Fox explains in his book on Alexander: “The Macedonian kings had long claimed to be of Greek descent, but the Greeks had seldom been convinced by these northerners’ insistence and only to flatterers was Philip anything better than a foreign outsider.”

The classical Greeks could not bring themselves to agree that Macedonians were Hellenes. Why, then, do present-day Greeks assert with the obduracy of unmovable conviction that Alexander was Greek?

The one thing that seems to go unquestioned in this international quarrel is the real worth of Alexander’s legacy.

Alexander the Great certainly had ambition, style and a superb military mind, but in essence he was a butcher who, toward the end of his life, lost his grip on reality. He murdered his comrade, the general Cleitus, at a dinner party, then knelt down and cried.

More egregious still, Alexander introduced a pernicious idea into the western bloodstream: That of the “god king”. Convinced that he was the son of Zeus, Alexander asked to be worshipped as a deity. In so doing, he broke with a centuries-long Greek insistence on the separation between mortals and immortals. The question of whether he was Greek or quasi-Greek can be endlessly debated. What is certain is that he trashed a good Greek idea.

— Los Angeles Times

Luke Slattery is a writer and journalist and honorary associate of the University of Sydney’s department of classics and ancient history.