When linguistic niceties fall clear by the wayside

‘Who’ is being exiled from its rightful habitat as an increasing number of American politicians opt for the more inanimate ‘that’

I first noticed it during the 2016 Republican presidential debates, which were crazy-making for so many reasons that I’m not sure how I zeroed in on this one. “Who” was being exiled from its rightful habitat. It was a linguistic bonobo: endangered, possibly en route to extinction.

Instead of saying “people who,” Donald Trump said “people that.” Marco Rubio followed suit. Even Jeb Bush, putatively the brainy one, was “that”-ing when he should have been “who”-ing, so I was cringing when I should have been oohing.

It’s always a dangerous thing when politicians get near the English language: Run for the exits and cover the children’s ears. But this bit of wreckage particularly bothered me. This was — who, a pronoun that acknowledges our humanity, our personhood, separating us from the flotsam and jetsam out there. We’re supposed to refer to “the trash that” we took out or “the table that” we discovered at a flea market. We’re not supposed to refer to “people that call my office” (Rubio) or “people that come with a legal visa and overstay” (Bush).

Or so I always assumed, but this nicety is clearly falling by the wayside, and I can’t shake the feeling that its plunge is part of a larger story, a reflection of so much else that is going wrong in this warped world of ours.

Few of our politicians aspire to old-fashioned eloquence anymore. Fewer still attain it. Most can’t manage basic grammatical coherence, and they’re less likely to be punished for that than to be rewarded for it by voters who see it as a badge of their authenticity.

I see it less charitably and would have no problem with a spelling test as a presidential prerequisite, though maybe that’s just my way of inventing a criterion that would have weeded out a certain real estate tycoon. You know, the one whose “unpresidented” ascent gave us a leader who says he is “honered” by his office, is not “bought and payed for,” was once victim of a “tapp” on his phones, and is obviously unfamiliar with the face-saving virtues of autocorrect.

But then we’re all plenty sloppy these days, pulled toward staccato bluntness by the teeny-tiny keypads on our smartphones and the 140-character limit on our tweets. We communicate in uppercase abbreviations (LOL, ICYMI, TTYL) and splenetic bursts, with such an epidemic of exclamation points that each has no more drama than a comma.

The deployment of “that” in lieu of “who” doesn’t actually rate very high on the messiness meter. It’s defensible, because while some usage and style guides — including The New York Times’ — call for “who” and “whom” when people are involved, others say it’s elective.

The Merriam-Webster dictionary blesses “that” in relation to people. So does the American Heritage dictionary, noting, “’That’ has been used in this way for centuries.” It cites examples from the King James Bible and from no less a master of the English language than Shakespeare.

Dissatisfaction and disagreement persist

But dissatisfaction with “that” and disagreement about it persist. I traded emails with Mary Norris, the so-called comma queen at the New Yorker magazine, who once ruled the grammatical roost there. She told me, without equivocation: “When it’s a person the correct relative pronoun is ‘who’. My suspicion is that people are afraid of saying ‘who’ when it should be ‘whom’ (or vice versa, which is way worse), so they sidestep the issue by using ‘that.’”

Connie Eble, the resident grammar guru at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told me that she’ll shepherd students toward “who” and “whom” even though she acknowledges the historical and technical validity of “that.” And there was unmistakable sadness in her voice when she concurred with me that “that” is getting an ever heavier workout these days, saying, “The space that ‘that’ is occupying is growing and growing and growing.” It’s not a pronoun. It’s the Blob.

I just crave less “that,” which I’m hearing from Democrats and Republicans alike and from people with extensive education and great vanity about their erudition as well as people who hold fast to a more plain-spoken identity.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, with all her accolades and best sellers, wondered on Morning Joe recently if Trump would wind up disappointing “the people that he promised” new jobs. Ah, Trump. He’s our “that”-er in chief. He’s all “that” all the time. At a rally in Des Moines, Iowa, in December, he told the audience that he wanted, in his Cabinet, “people that have made a fortune.”

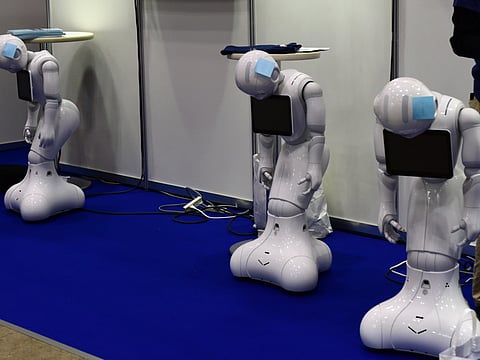

How did we get here? Why is “who” on the ropes? One of my theories is that in this hypercasual culture of ours, we’re so petrified of sounding overly fussy that we’ve swerved all the way to overly crass. And my fear is that there’s a metaphor here: something about the age of automation, about the disappearing line between humans and machines. The robots are coming. Maybe we’re killing off “who” to avoid the pain of having them demand — and get — it.

— New York Times News Service

Frank Bruni is a writer and author of Born Round and Ambling into History.