‘Can someone in Spain explain to me exactly what’s going on with PSOE ?” wrote Guardian columnist Owen Jones last Wednesday on his Twitter feed .

His bafflement is understandable. It is as if hell has broken loose in the 137-year-old Spanish socialist party, which is bitterly divided in ways that recall the current schism in British Labour.

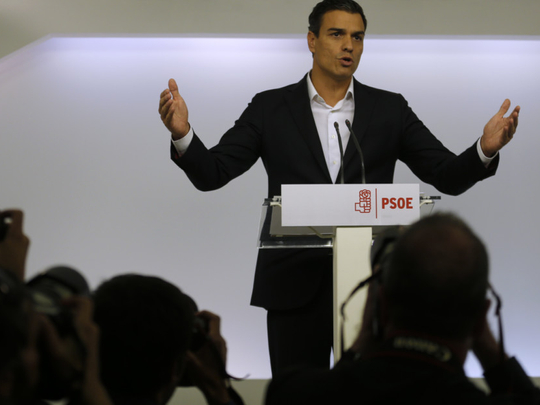

Half the organisation no longer recognises secretary general Pedro Sánchez as its leader and considers him ousted by the executive committee. But fuzzy party rules leave this open to interpretation. So Sánchez, with the support of the other half of the PSOE, has been barricading himself – quite literally, until this week − inside the party’s headquarters in Madrid. Outside the building a plaque recalls that it was in this very house where the founder of the Spanish socialist workers’ party , Pablo Iglesias Posse, passed away.

Considering the stakes, the immediate cause of this bitter argument seems a trifle: a mere difference of opinion on a matter of strategy. But it’s one that touches the core of the party’s identity. Spain has been in a deadlock for nine months now. After two indecisive elections it has been impossible to form a government, and a new vote looms in December.

The socialists have been doing badly in all previous polls, and Sánchez’s critics think it would be better to avoid a new defeat – even if that means abstaining in parliament to allow the formation of a minority conservative government, and preventing the election from going ahead.

On the other hand, Sánchez and his followers believe the socialists have a duty to oppose the right, regardless of the cost. They are even ready to form a difficult leftist coalition with the party Podemos and, more controversially, with the support of the Catalan pro-independence parties who are opposed by some socialists as strongly as they are by conservatives.

Deep down, here are two ways of understanding the role of the socialist party in Spain. One view is of the PSOE as a player in a two-party system with the conservative People’s party (PP). The socialists haven’t won this time, so they think it’s fair to let their rivals govern until their own turn comes. These are the rules to which all supporters of two-party systems, including most of the British Labour and Conservative parties, subscribe. Sánchez, though, believes we have entered a new political landscape, one in which new forces in the centre ( Ciudadanos party ) and the left (Podemos) have broken the old consensus – much as some are arguing that the two-party system is broken in the UK.

In the case of Spain, both arguments have their flaws. Sánchez is right in his diagnosis of a new political landscape, but it is one that affects mostly the socialists. The PP remains relatively strong in spite of an endless series of corruption scandals, and is regaining support.

He can count on most of the membership in forging an alliance with Podemos, but voters are more moderate than members

Sánchez is also, perhaps, too optimistic about the flexibility of his electorate. While he can count on most of the membership to support him in forging an alliance with Podemos, socialist voters are typically more moderate than members, and many of them would abstain or switch sides if Sánchez accepted the support of the Catalan nationalists.

There’s also a more superficial aspect to this quarrel. Those who oppose Sánchez are mostly nostalgic party grandees plus regional office-holders more interested in ending Spain’s political stalemate than in how it is ended.

As for Sánchez, his newly acquired leftist persona is unconvincing. When he won his leadership contest two years ago he was the establishment candidate, handpicked by the same party heavyweights who now want him out. Personal ambition is not unknown in politics, but Sánchez’s is so conspicuous that it weakens his case.

Two things could happen now, and neither looks good for the socialists. Sánchez may survive the coup, but the leftist coalition that could have made him PM is definitely off the table. Now it’s obvious that he can’t count on the support of his own parliamentary party. But if he’s ousted the critics may not get what they want either. They would be free at last to help the conservatives into government and thus avoid a new election, but after all that’s already happened this could destroy their party. And as things stand, the conservatives have every incentive to call new elections. It could yield them an absolute majority, or close to it.

Many expect the conflict to benefit Podemos, which has been in a downward spiral. This is possible. The PSOE has already lost many votes to them and could give up a few more if Sánchez is fired. But this is unlikely to offset the gains of the conservatives, and a coalition with the PSOE would then be out of the question. A lot was expected from the “new political landscape” in Spain. As it turns out, new factors don’t necessarily mean different outcomes.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Miguel-Anxo Murado is a Spanish writer and journalist.