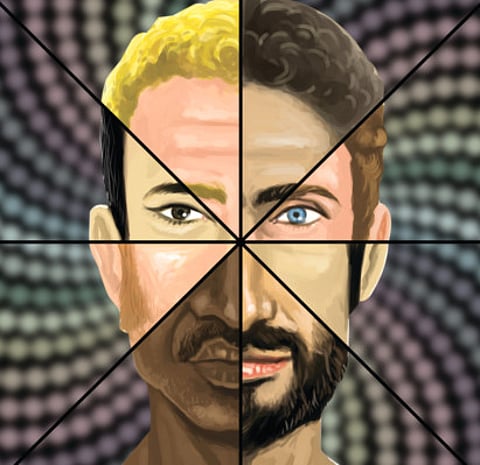

What is it about skin colour?

Educating children and youths about evolution of skin colour may be effective

Skin colour is one of our most important biological traits. Its many shades evolved as humans moved far and wide into regions with different intensities of sunlight. Skin colour is also a trait that has come to have deep cultural meanings — developed over many centuries — that influence our social interactions and societies in profound and complex ways.

We notice one another’s skin because we are visually oriented animals, but there is no genetically programmed bias to favour one colour over another. Over time, however, we have developed beliefs and biases about skin colour that have been transmitted over decades and centuries and across vast oceans and continents. The first scientific classification of humans, published by Carl Linnaeus in 1735, was simple and separated people into four varieties by skin colour and continent. Later, Linnaeus not only added more physical traits to his descriptions, but also changed them to include information that he had surmised about temperament.

Europeans were white and “sanguine,” Asians were brown and “melancholic,” Native Americans were red and “choleric” and Africans were black and “phlegmatic”. This analysis was the first authoritative classification that combined physical traits with folk beliefs about dispositions and character. The folk beliefs had little to do with fact or observation, but were mostly just fables — racist pronouncements that were personal and emotional expressions of, at best, discomfort and, mostly, prejudice.

From this point on, debasing associations of physical appearance with temperament and culture became commonplace and were considered scientific. Racism had found its intellectual foundation.

The first person to formally define “races” was the noted philosopher Immanuel Kant, who, in 1785, classified people into four fixed races, which were arrayed in a hierarchy according to colour and talent. Kant had scant personal knowledge of human diversity, but opined freely about the tastes and finer feelings of groups about which he knew nothing. For Kant and his many followers, the rank-ordering of races by skin colour and character created a self-evident order of nature that implied that light-coloured races were superior and destined to be served by the innately inferior, darker-coloured ones.

Despite the strong objections of many of his contemporaries, Kant’s ideas about a fixed natural hierarchy of human races, graded in value from light to dark, gained tremendous support because they reinforced popular misconceptions about dark skin being more than a physical trait. The preference for light over dark — strictly speaking, white over black — was derived from pre-medieval associations of white with purity and virtue, and of black with impurity and evil. The light-dark polarity was extended to the human sphere with the establishment of slave trade and hereditary slavery in the Americas. Negative associations of dark skin and human worth became profitable.

As the transatlantic slave trade became more lucrative, the moral polarity of skin colours was accentuated to the extent that light and dark were respectively associated with human and animal, creating one of the most sinister and long-lived patterns of unfairness that the world has ever known. The notion that the superiority of the white race was part of the natural order was deviously reinforced by the rise of modern “scientific” racism in the late 19th century. Certain “stocks” of humanity were considered to be more highly evolved and civilised because of their colour, superior “fitness” and “adaptations”.

“Racial souls” were seen as mapping onto unique suites of physical traits, creating crazy ideas of ranked human types and civilisations. The association of colour with character and the consequent ranking of people according to colour stands as humanity’s most momentous logical fallacy. Today, one of the biggest concerns is the reinvention of clinical concepts of race, based on inaccurate generalisations about the susceptibility of people to certain disease risks. If clinical constituencies redefine and repackage the races as real biological entities, then we face a new era of scientific racism no less frightening than the first.

Clinical authorities hold a sanctified place in American society and are capable of creating a new reality of labelled races that will be widely believed and promulgated because it is “for the good”. The idea that race is a social construct is becoming more widespread, but that does not diminish scientific racism as a real concept in the minds of many people who want to believe in it. Nor does it lessen the lived experience of racism today.

Racist beliefs, anchored in the scientific racism of a bygone era, persist today, but are mostly hidden because it is socially and politically unacceptable to air them. Indeed, the bankrupt concept of fixed and immutable human “races” — packages of physical and behavioural traits — ranked by colour has led to the creation of potent and persistent racial stereotypes.

When these stereotypes are propagated widely by revered authorities and transmitted faithfully from person to person and generation to generation, they can last and last. “Races” are not just labels, because they can determine fate.

Race labels that are associated with negative or positive depictions and narratives can have powerful effects by planting in people’s minds the idea that their own group is superior, inferior, smarter, stronger or weaker than another. Stereotypes are not realities and the behaviours they engender are not inevitabilities.

Human attitudes are constantly subject to revision through experience and, more importantly, through conscious choice. Biases can be modified and eradicated on the basis of experience and motivation and stereotypes can be changed when people are motivated to think about someone, in any way, as a member of their own group. Educating our children and youths about the evolution of skin colour, the history of race and the dangers of stereotyping may have remarkable and positive results for humanity.

— Washington Post

Nina G. Jablonski is distinguished professor of anthropology at Pennsylvania State University. This essay is based on her new book Living Colour: The Biological and Social Meaning of Skin Colour.