Coming from someone who has been so deeply involved in shaping the Donald Trump administration’s approach to world affairs, the comments made by Steve Bannon, the United States president’s former chief strategist, on the dramatic changes taking place in the Middle East merit serious consideration.

Reflecting on the US-led coalition’s success in destroying Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Syria) in Raqqa and Mosul, Bannon said he believed the most important confrontation facing the world now was not that with Daesh. It is instead the stand-off between Saudi Arabia, with other moderate Arab states, and the tiny Gulf country of Qatar over its support for Islamist terror groups and close ties with Iran.

The diplomatic rift between Qatar and the anti-terror quartet of Egypt, Bahrain, the UAE and Saudi Arabia has certainly generated a great many headlines, not least over the issue of whether Qatar will be able to host the 2022 football World Cup if its neighbours persist with their boycott.

Yet, few foreign policy experts have viewed the renewal of tensions between the Gulf states in the same terms as other major threats, such as North Korea’s missile programme, China’s plans to become the world’s leading power and the military adventurism of Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The most common view of the Qatar issue is that it is a family squabble that has got out of hand, and that at some point — certainly long before the World Cup takes place — the warring parties will settle their differences.

That Bannon, who has been a staunch supporter of Trump’s no-nonsense approach to tackling Daesh, should view the rift so differently provides an interesting insight into American policy, as well as having some important lessons for America’s own foreign policy establishment.

As Trump nears the end of his first year in the White House, we have learnt he has a Manichean view of the world, one where the globe is simply divided between countries that support America and its interests, and those that do not.

When applied to the Middle East, where extremism poses the greatest threat to the US and its allies, this approach means that the Trump administration is likely to take a dim view of countries such as Qatar and Iran that have a long and undistinguished history of supporting extremists.

Penchant for speaking the truth

It is no surprise that the anti-terror quartet’s move against Qatar came immediately after Trump’s visit to Saudi Arabia this summer, during which he was given a detailed briefing on how Doha was sponsoring terror groups around the Middle East, thereby undermining Washington’s attempts to imbue the region with a degree of stability. The US president’s recent public rebuke of Iran for its constant meddling in the affairs of Arab states, as well as its support for terror groups such as Hezbollah, is another example of the Trump administration’s penchant for speaking the truth unto terror-supporting regimes.

Moreover, now that the military campaign against Daesh is winding down, it is more important than ever that countries like the US and Britain act forcefully to prevent the terrorists’ evil creed from spreading to other parts of the region.

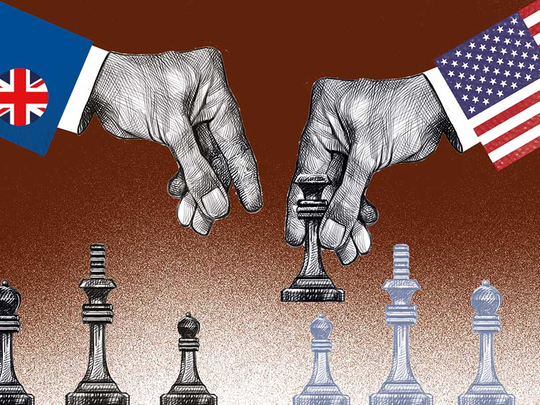

However, while the American president deserves credit for his robust stand against state-sponsored terrorism, Britain is sending mixed messages to friends and foes alike. British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson’s desire to sit on the diplomatic fence was evident in his Chatham House speech this week, when he extolled the virtues of Trump taking a firm line on North Korea’s pursuit of nuclear weapons and, in virtually the same breath, rejected the president’s stand on Iran.

As Brexit nears, and the government in London seeks new trade opportunities, it is important that Britain works out which countries are well-disposed to its interests and which are hostile.

Rather than offering to sell the Qataris Eurofighter warplanes, Britain’s interests would be far better served by developing the strong and long-standing ties it already has with countries such as Saudi Arabia.

These are exciting times for the Saudis, the majority of whose population is under the age of 30. An economic and social revolution, known as Vision 2030, is being driven through by the country’s dynamic Crown Prince, Mohammad Bin Salman.

However, Britain’s ability to take advantage of the wealth of opportunities that the Vision 2030 programme will throw up, is likely to depend to a large extent on the government’s ability to choose, as Trump is doing, between countries, like Saudi Arabia, that are Britain’s friends, and those that are not.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2017

Con Coughlin is the Daily Telegraph’s defence editor and chief foreign affairs columnist.