Venezuelan presidential candidate, Henrique Capriles Radonski, is hoping to complete a trifecta of victories against the country’s vice-presidents in next month’s election to choose a successor to deceased leader Hugo Chavez. Back in 2008, Capriles had upset Chavez’s right-hand man and former vice-president, Diosdado Cabello — now the head of the national assembly — and was elected governor of the populous state of Miranda.

Last December, he bested another former vice-president, Elas Jaua — now Foreign Minister — to win re-election. Both of these were impressive victories. The government had spent heavily in the hope of ousting him, but the third victory will undoubtedly be the toughest.

Capriles, who is regarded as the opposition’s best and perhaps only, hope to retake the country’s presidency, is facing acting President Nicols Maduro, whom Chavez chose as his vice-president in October. In addition to access to the substantial resources of the state, Maduro is riding high on a wave of public sympathy for Chavez, who died on March 5 after a two-year bout with cancer. It is also Capriles’s second presidential race in less than a year: Chavez beat him last October, though it was the closest-fought campaign of the late president’s 14-year tenure.

“The election is going to be a referendum on what kind of man, what kind of president Hugo Chavez was,” said Ray Walzer, a fellow at the Washington-based Heritage Foundation. “The problem for Capriles is that Venezuela is in a post-Chavez hangover now.” Polls matching Capriles and Maduro and taken before Chavez’s death showed the latter with a strong double-digit lead, ranging from 10 to 15 percentage points.

However, Capriles has come out swinging this time, in marked contrast to his race last year when some advisers felt he was too deferential to the ailing president and did not attack Chavez’s policies enough. They also faulted him for not responding to Chavez’s personal insults.

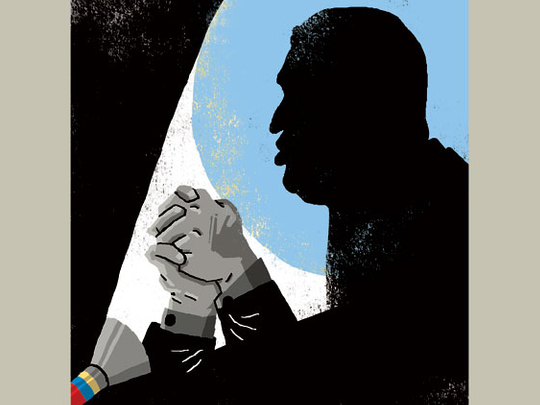

“Candidate Capriles is going to be much more forceful this time, more direct and questioning,” said an adviser to the challenger, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Last time he was too polite, which was viewed as a weakness. This time, the gloves are off.”

Capriles has wasted no time in going on the attack since accepting the nomination from the opposition coalition front to contest the April 14 election. He has repeatedly charged that Maduro, 50, lied to the Venezuelans about the date and circumstances of Chavez’s death, to give himself more time to fortify his position. His stump speech hammers the acting president, claiming that Maduro’s first 100 days in office have been a disaster, highlighted by the decision to devalue the country’s currency by 32 per cent. “Nicols has been campaigning ever since President Hugo Chavez went for his treatment,” Capriles said in a meeting on March 12 with journalists. “We’re already 100 days into Nicolas’ government and look where our country is going. He is a bad imitation of the president.”

There is little love lost between the two men. During last year’s campaign, Maduro backers whispered that Capriles is Jewish — which he is not. Maduro stepped up the accusations earlier this month, internationalising the dispute, when he said that Capriles had gone to the US to conspire to overthrow the government with the collusion of US intelligence agents. Capriles said the trip (he visited Miami and New York the week prior to Chavez’s death) was to visit family members and tweeted photos of himself with his nephews. Now, and somewhat bizarrely, Maduro has accused Washington of plotting the assassination of Capriles.

The government has already expelled US officials and just suspended talks to improve relations between Washington and Caracas, following US Undersecretary of State for Latin America, Roberta Jacobson’s call for Venezuela to stage free and transparent elections. Capriles makes no secret of his disdain for Maduro, constantly calling him by his first name and refusing to refer to him as president, noting that he was never elected to the position. He accuses Maduro of hiding behind Chavez’s image to avoid taking any blame for bad decisions.

Maduro counters by accusing Capriles of dishonouring Chavez’s memory and of being disrespectful to the president’s family. (He was neither invited nor allowed to attend the funeral.) Maduro has also been careful to identify himself as “a son of Chavez” and constantly sprinkles his speeches with references to the fallen leader. He often speaks in public with a picture of Chavez in the background, looking over his shoulder, much like his old boss did with Simon Bolivar. “Maduro isn’t Chavez, but then he doesn’t need to be,” said David Smilde, a senior fellow at the Washington Office for Latin America. “He is still basking in the glow of Chavez.”

Smilde noted that Capriles needs to stop mentioning Chavez as the root of all ills and start sharing his plans for the future. Venezuela’s economy and soaring crime are the issues that resonate most with voters. Since the devaluation, prices have soared. Although the official exchange rate is 6.3 bolivars to the dollar (Dh3.67), it was trading at 26 on the black market in the days after Chavez’s death before falling back to 23.50. Basic foodstuff such as coffee, sugar, cooking oil, corn meal and meat — the prices of which are set by the government — remain scarce.

“I may be a Chavista,” said Nora Alvarez, a 28-year-old housewife waiting in a queue outside a supermarket in Caracas. “But this is ridiculous. I am wasting four hours just to buy four kilograms of corn meal. We never went through this before.”

Crime is also surging. Maduro said last week that he would seek to talk to the leaders of Venezuela’s crime gangs to convince them to put down their arms. Failing that, he said he would send in the police, national guard and army to hunt them down. Capriles and members of the opposition ridiculed Maduro’s entreaty, saying it was unrealistic to hope the gangs would voluntarily give up their life of crime.

“This election is an important one for Capriles and the opposition to get their ideas out there, to get a message to the country that they have alternative policies, and ideas for the country,” said Smilde. “Then he will be in a position in the future, when things get tough for Maduro, to offer Venezuelans a different path, a different message.”

So far, however, Maduro is sticking with a simple message: ‘I am the heir to Chavez; stick with me’. Maduro’s campaign literature prominently features a picture of Chavez above the words ‘Maduro from the heart’. Occasionally, the imitation verges on self-parody. Maduro has started singing at public appearances, just as Chavez did and has started tweeting. However, Maduro may have lost perhaps the key prop in his election bid. It may be too late to embalm Chavez’s body to have it placed on permanent display, Maduro said last weekend.

The government had planned to place the former president’s remains in a glass case so he could inspire future generations and influence elections. “There are difficulties and those difficulties may make it impossible to do what they did to Lenin, Ho Chi Minh or Mao,” Maduro said. But Maduro’s backers may not need the former president’s corpse to win. They are spending freely to get their message out, plastering Chavez’s image in their campaign signs and advertisements.

El Comandante may not be there in person, but his shadow and memory still looms large.

— Washington Post

Wilson is a journalist who has lived in Venezuela since 1992. The Caracas bureau chief for Bloomberg News for nearly 11 years, Wilson is writing a book on Hugo Chavez and his revolution.