Recently, in an effort to embarrass Republicans pandering to their scientifically challenged base, Senate Democrats proposed a series of votes on climate change. While most Americans and the overwhelming majority of scientists believe climate change is real and people are the primary cause of it, Republican voters are evenly divided on whether it exists at all and reject the idea that we are responsible.

One amendment, by the Democratic senator Brian Schatz, stated simply that climate change is real and human activity significantly contributes to it. Republican senator John Hoeven offered a compromise : take the word “significantly” out. When asked why, he said: “It was about finding that balance that would bring bipartisan support to the bill.” Reaching across the aisle in search of compromise and consensus is the professed goal of almost every candidate for public office in the US, particularly in recent times, when presidents have come to personify not unity but division. Over the past six decades, the 10 most polarising years in terms of presidential approval have been under either George W. Bush or Barack Obama.

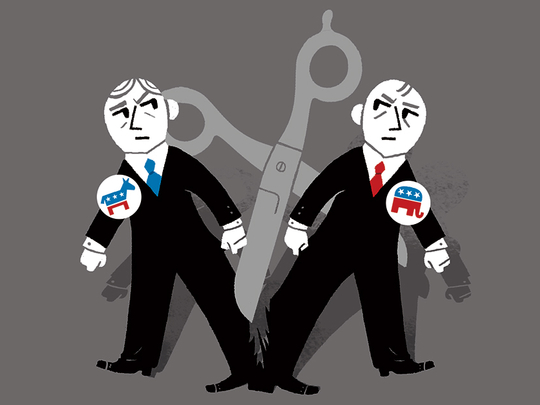

As a means, bipartisanship is, of course, an admirable goal: The more politicians are able to work together, put the interests of their constituents first and get things done, the better. The grandstanding, bickering and procedural one-upmanship that characterises so much of what passes for politics is one of the things that makes electorates cynical and drives down voter turnout. But as an end in itself, bipartisanship is at best shallow and at worst corrosive. For it entirely depends what parties are joining together to do. This is particularly true in America, where constituencies are openly gerrymandered, both parties are funded by big money and legislation is often written by corporate lobbyists.

Bipartisan efforts over the past couple of decades have produced the Iraq war, the deregulation of the financial industry, the bank bailout made necessary by that deregulation, the slashing of welfare to the poor, and an exponential increase in incarceration. As the hapless Steve Martin says to his hopeless travel companion, John Candy, in Planes, Trains and Automobiles: “You know, I was thinking, when we put our heads together ... we’ve really gotten nowhere.”

Comity in the polity is overrated and should certainly not be mistaken for what is right or even popular. And even if it wasn’t overrated, bipartisanship is not always possible. Half of Republicans still believe the US did find weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, over half believe climate change is a hoax , and almost half do not believe in evolution. There is a limit to how much agreement you can reach with people with whom you disagree on fundamental matters of fact, let alone principle. But if the parties cannot work together, they are at least supposed to work separately. What has become evident since Republican victories in November’s midterm elections, which delivered them both houses of Congress, is that they do not just have a problem compromising with Democrats — they cannot even compromise with each other.

For the past four years, they have revelled in their dysfunctionality, using Obama as a foil. Apparently unaware that brinkmanship is supposed to take you to the edge, not over it, they have shut down the government and almost forced the nation to default on its debts through a series a spectacular temper tantrums. As the Republican congressman Marlin Stutzman pointed out in a particularly candid moment 18 months ago, when Republican obduracy caused a government shutdown, “We have to get something out of this. And I don’t know what that even is”.

These hissy fits have invariably been aimed at forcing Obama to undo the very things he pledged to do if elected, and to which Republicans have no plausible, coherent response: During his first term that was Obamacare; now it is immigration reform.

Opposition, in short, had become not a temporary electoral state, but a permanent ideological mindset in which their role was not to produce workable ideas but to resist them. When they won the Senate as well as the House, they were supposed to work together to produce Republican legislation that Obama would be forced to veto, definitively exposing the real source of the gridlock. In fact, they are simply imploding under the weight of their own obstinacy. They have run out of people to blame for not compromising with them. So now they are blaming each other.

“The Republicans are like Fido when he finally catches the car,” the Democratic senator Charles Schumer told the New York Times. “Now they don’t have any clue about what to do. They are realising that being in the majority is both less fun and more difficult than they thought.” Their current internal feud was prompted by Obama’s executive order for modest immigration reform, which was enacted last November. It aims to prevent the deportation of up to five million undocumented immigrants living in the US, provide many with work permits, and shift the focus of immigration control to deportations of convicted criminals and recent arrivals. The Republican-controlled House, where funding bills must originate and legislation can be passed by a simple majority, has voted for a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) bill that would eviscerate Obama’s reforms. But to get the bill through the 100-seat Senate they need 60 votes. Senate Republicans have only 54 seats and Democrats, who are unanimously opposed to the bill, keep filibustering it.

In a functional party, the Republican Speaker, John Boehner, would work out what changes he could make to the bill to give the Republican Senate majority leader, Mitch McConnell, a fighting chance of getting the requisite majority to pass legislation they could both take credit for. Instead, Boehner has offered McConnell not compromise but commiserations. “He’s got a tough job over there; I’ve got a tough job over here. God bless him, and good luck.”

The House has sent the same bill to the Senate twice. The Senate has failed to pass it several times. In effect, they have treated the Republican-controlled Senate no differently to how they treated its Democratic predecessor, with similar results. Reflexively, House Republicans have their bottom lip extended and at the ready. “We sent them a bill,” representative Michael Burgess told Politico, “and they need to pass it. They need to pass our bill”. A tantrum is not far off. “Politically, [McConnell] needs to make a lot of noise,” says representative John Carter.

Senate Republicans, meanwhile, roll their eyes, count to 10 and wait patiently for the noise to give way to reason. “We can go through the motions, sure, but I don’t think we’re fooling anybody,” said Republican senator Jeff Flake about the prospect of another doomed vote. “Because we need [Democratic] support to get on the bill.” If they don’t find a solution by February 27, then the DHS will be shut down and Obama will not have had a thing to do with it.

The true source of the gridlock over the past six years will be clearer than ever. The emperor will be out there, twerking, in the buff. “It’s not an issue of commitment, it’s a matter of math,” said Republican senator John McCain — perhaps failing to realise that math, like science, is no competition for blind faith and bad politics.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd