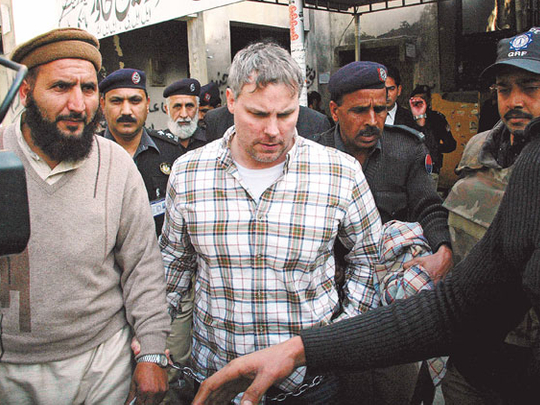

Although Pakistan-US relations have experienced an unprecedented low over the Raymond Davis crisis, both governments recognise that they can ill-afford the bilateral relationship going sour. Yet the knee-jerk reaction after Davis' arrest was one of anger.

In an imperial mode of diplomacy, Washington issued threats of cutting off aid and postponed several high-level bilateral meetings. Washington insisted Davis — arrested by Pakistani authorities for fatally shooting two Pakistani men in Lahore — was innocent, killed in self-defence and has full diplomatic immunity

However, almost three weeks into the Davis saga, Washington has recognised that on an issue that has strong legal, political and popular traction in the country, Pakistan's point of view on immunity cannot simply be brushed aside with threats.

Washington's rhetoric has subsided and high-level contact, which initially began with arguments and counter-arguments have now moved towards genuine dialogue.

Even Pakistan's former foreign minister Shah Mahmoud Quraishi, whose removal from the post was largely seen as a result of US displeasure over his position that Davis did not qualify for diplomatic immunity, said in a press conference yesterday after meeting US Senator John Kerry that "I understand the importance of messaging, I understand US concerns, but shouldn't they look at my concerns? Let's calm down and look at the larger picture."

With Senator Kerry's arrival in Pakistan, Washington's demands and threats have translated into genuine dialogue and a search for a mutually acceptable solution. Washington's earlier demand that Davis must be released is now being tempered by a commitment that he will be tried by a US court.

More importantly, Washington has agreed to present its case of diplomatic immunity before the Lahore High Court today. On the same day, the Pakistan's government's position will also be presented before the court.

Grey areas

Significantly, despite the Pakistan government's clear position that Davis cannot be released under diplomatic immunity and the US insisting that such immunity exists, some grey areas of interpretation may appear in the different vantage points.

Pakistan's Foreign Office obviously invokes the Pakistan's Diplomatic and Consular Privileges Act, 1972 while ruling on diplomatic immunity.

The US, meanwhile, is invoking the Vienna Convention of 1961.

Pakistan Foreign Office says that Pakistan's Diplomatic and Consular Privileges Act, 1972, allowed no space to the government to covertly send off Davis. The Consular Privileges Act 1972, which guides how the government of Pakistan provides diplomatic immunity to foreign government employees, is the Pakistani law in which Pakistan has incorporated the Vienna Convention of 1961 and 1963.

The Pakistan and US conflicting positions flow from their different interpretations of who holds the final word on diplomatic immunity — the sending country or the receiving country — and the conditions under which diplomatic immunity can be provided.

The other question centres on Davis' activities as an alleged undercover agent. His job included making contact with militant groups in Waziristan. Guns, bullets and other items were found in his car, photographs of Pakistan's defence posts were found in his camera and his car bears a fake number plate.

Allegations

Washington will have to provide clarity on these issues. The US media too has made public some new information about Davis' past, including his stint as a special operations man.

In Pakistan, the public reaction to the Davis saga has been harsh. It flows from the anger that the public feels towards US double standards on human rights, on international law, the fallout of the war on terror on Pakistan, particularly in terms of drone attacks, the death of innocents in Afghanistan, Guantanamo Bay and Abu Gharib.

The question why the car and the driver that entered the US consulate, after crushing to death an innocent bystander on January 27, is not being handed over to Pakistani legal authorities is being raised.

The constant refrain remains whether the Pakistan government will give in to US pressure or withstand it. Is Pakistani life that cheap? First it was drone attacks and now it is the daylight killing of Pakistanis.

All of these are may be valid questions, but they are not the ones that should influence how the Pakistan government deals with the Davis case. The key question remains that of diplomatic immunity.

Meanwhile, the problems with this crisis-prone relationship are mirrored in popular narratives and polls. For example, according to the latest Gallup's annual World Affairs poll, Pakistan is categorised as one of the four least liked countries in the US. Similarly in Pakistan, the US is the least liked country, even less than India.

Clearly the chronic issue of mutual distrust needs to be addressed through more transparent and candid policy dialogue. And perhaps resolving the Davis crisis in a mutually acceptable way, could be an important step in that direction.

Nasim Zehra is a writer on security issues.