Sergey Kislyak, Russia’s long-serving ambassador to the United States, has a habit noticed by many US officials who have known the envoy. Kislyak shows up everywhere and tries to talk to everyone.

“He doesn’t get as much credit as he should, in my view, for being savvy about developing relationships with people all over the city,” said Michael McFaul, who knew the diplomat well while serving in the Obama administration as senior adviser on Russia and then as US ambassador to Russia.

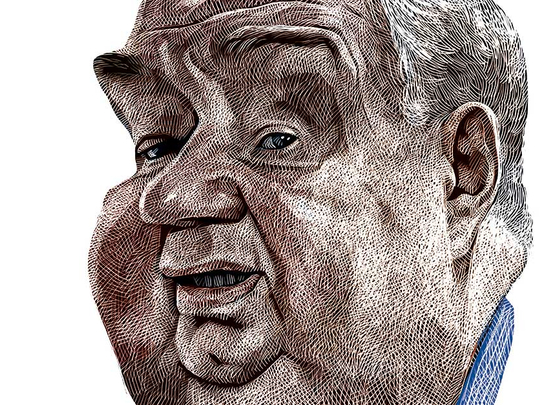

Moscow’s man in Washington, DC, is an unlikely man of the political moment, however. He is quiet, careful, rumpled and portly. He is a fierce defender of Russia’s international prestige who rarely gives interviews and even more rarely makes news on his own. He is not considered especially close to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

For Kislyak to have sought contacts with former national security adviser Michael Flynn and Attorney General Jeff Sessions in 2016 when the latter was a US senator should come as no surprise, current and former US officials said.

Flynn, a retired Army lieutenant general and former head of the Defence Intelligence Agency, was a top national security adviser and frequent warm-up act for Trump during the campaign. He was forced out as national security adviser at the White House over concerns he had misled Vice- President Mike Pence and others about his contacts with Kislyak before Trump took office.

Sessions, then a US senator from Alabama, was among Trump’s early supporters in Congress and went on television to promote the candidate. He has come under scrutiny for two meetings with Kislyak last year.

The Russian diplomat, who speaks excellent English, seems to know American officials, past and present, across the political and ideological spectrum. Several Americans who know him say he prides himself on proximity — he always seems to have just had dinner with someone influential or just happens to be seated up front at newsworthy foreign policy events.

John McLaughlin, a former deputy CIA director and acting CIA director under former president Barack Obama, said that “it does strain credibility” that Sessions would have simply forgotten about his meetings with Kislyak when he asserted during his confirmation hearing to become attorney general that he had not met with Russian officials.

“I know Ambassador Kislyak. He’s a veteran of Russian diplomacy, and he’s a hard guy to forget if you’ve met with him,” McLaughlin said during an interview on Thursday with MSNBC host Andrea Mitchell.

Sessions said at a news conference on Thursday that he was “taken aback” by a question — which referred to a breaking news story about contacts between Trump campaign surrogates and Russians. “In retrospect, I should have slowed down and said I did meet one Russian official a couple times. That would be the ambassador,” he said.

Kislyak arrived as ambassador in 2008, a few months before the start of the Obama administration, and is expected to leave this spring. His replacement has not been announced. The Russian Embassy did not respond to a request for an interview with Kislyak.

Most of the ambassador’s outreach efforts focus on the executive branch, as is the custom for Russian diplomats whose political system back home is top-down. Lawmakers are often reluctant to meet with senior Russian officials independently because diplomacy and intelligence gathering tend to blur for Moscow’s representatives in the United States.

Still, the Sessions contacts on their own are of a piece with what foreign ambassadors, and especially Kislyak, see as a part of their job, current and former US officials and Russia experts said.

“It seems entirely routine for the ambassador of a foreign government to want to meet with senators, for example, and especially one who is a member of the Armed Services Committee,” said Paul Saunders, a Russia specialist at the Centre for the National Interest and a former official in the George W. Bush administration. Most members of the Armed Services Committee, however, told The Post that they had not met with Kislyak last year.

Saunders’ group hosted then-candidate Donald Trump for a foreign policy speech in April last year. Kislyak was in the audience as one of four invited foreign ambassadors as Trump proclaimed, “America-first will be the major and overriding theme of my administration.”

Kislyak is known to collect scores of business cards as he moves around Washington, and to follow up, sometimes relentlessly, with requests for one-on-one meetings. Sessions said Thursday that Kislyak had also invited him to lunch, an invitation he never took up.

“He was constantly doing that when I was in the government,” McFaul said of Kislyak’s ability to speak to US officials at the Pentagon and elsewhere, sometimes without the White House knowing about it first. “At times it would be frustrating to us.”

Kislyak, a physicist and arms-control expert by training, has succeeded as a diplomat by voicing the official Russian line on all issues in genial terms, and within the hierarchy of Russian diplomacy by always having fresh news, gossip and political analysis to feed back home.

It is not clear how much Kislyak knew about what US intelligence officials have said was a concerted Russian government effort to influence the US presidential election, although it is likely that he was at least aware of it, said Steven Hall, former head of Russia operations at the CIA.

In the case of Sessions, who was considered a top prospect for a Cabinet job when Kislyak visited him in his Senate office in September, Kislyak would have wanted to know: How reasonable is he from a Russia perspective? Hall said.

Kislyak denied that Russia was meddling in the election during an address to the Detroit Economic Club less than two weeks before the November 8 election.

“We have become kind of collateral damage in the fight between the two parties,” he said, adding that Russia is “ready to work with any president that is going to be elected.”

Opinions differ on whether Kislyak is a spy in the American sense of the word.

“For them it’s much greyer,” Hall said of the Russian view of the difference between a diplomat and spy. “I would say [Kislyak] is most definitely both. In the Russian system, it’s simply assumed that they’re all collecting and doing whatever they can either covertly or overtly.”

— Washington Post