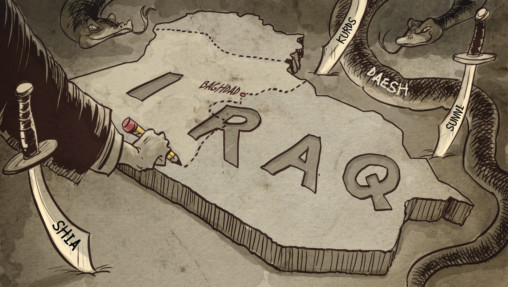

The borders of Iraq that emerged as European powers betrayed promises to Arabs and Kurds might soon be erased, but the process of creating something different is likely to generate new grievances that could fuel conflict for many years.

In 1916, the French and British determined in the Sykes-Picot agreement that, after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Britain would have control or influence over the area that later became Iraq. This treaty, and the subsequent treaties and policies that followed, would, in the end, betray Britain’s Arab nationalist allies and the Kurds. Britain eventually stitched Iraq together out of three Ottoman vilayets — Mosul, Baghdad and Basra, laying the foundation for a century of instability and violence.

Drawing borders that would support the creation of a viable, sovereign state was not in the forefront of the minds of the colonial mapmakers, despite vague promises of eventual self-rule. British geostrategic interests, on-the-ground military realities and colonial negotiators’ give-and-take were far more important. The European colonial powers sought to create territories they could directly or indirectly control.

In 1920, practically as soon as the new mandates’ borders were determined, the British faced an uprising. Anti-government instability and occasional revolts continued through the British colonial rule to 1932, the Hashemite monarchy (under British influence) to 1958, a string of military rulers and then Saddam Hussain from 1979 to 2003. All faced regular instability, including Shiite and Kurdish revolts.

Arguably, aside from a ruling elite, it is unclear whether most Iraqis embraced a national identity. As is often the case in which a demographic minority rules a country, the Sunni rulers used brutal repression against many Shiite Arabs, Kurds and others. Once Hussain was removed following the United States-led 2003 invasion, all of this boiled to the surface, with horrific violence perpetrated by various communities against each other.

Washington aimed to rebuild Iraq as a unified, democratic country that included all the major groups in a cooperative government. In theory, this was and is a good solution for the problem of the artificial creation of Iraq — one that offered the best chance at meeting the various groups’ interests while avoiding the risks associated with dividing the country. Unfortunately, it has not worked for many reasons, including deep distrust between communities.

Today, the country seems in limbo between continued efforts to make a federal, democratic Iraq work and the reality of growing decentralisation. The Sunnis — split between areas controlled by Iraq and those by Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levnat) — want far greater decentralisation. Daesh’s control of large parts of western Iraq and its erasure of much of the border with Syria makes a mockery of the idea of Iraq as a sovereign state. Given their largely negative experience with a Shiite-dominated government in Iraq, Sunnis are unlikely to accept anything less than significant autonomy. The Shiites have less interest in dividing up Iraq, but, even in the south, some Shiite leaders advocate greater local powers.

The Kurds are often cited as one of the world’s biggest nations without a state. The 1920 Treaty of Sevres promised autonomy for the Kurds and the possibility of future statehood. The colonial powers abandoned this promise later, dividing the Kurds between Turkey, Iraq, Syria and Iran. Since the US provided a no-fly zone in northern Iraq in 1991 to protect the Kurds from Hussain, they have essentially self-governed themselves in the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) area. Today, the KRG is independent in many ways, including Kurdish security forces that have fought against Daesh, though it remains entangled with Baghdad in terms of fiscal arrangements.

The British-created conception of Iraq has failed. The US attempt to create a federal, democratic state is on life-support, if not already dead. So now what?

One option for Iraqis and relevant outside powers is to keep trying to develop a unified, federal Iraq that can incentivise all major groups to participate. If this can work, it remains the best option to prevent further violence and create a functioning state. This remains official US policy. However, even the Iraqis, foreign officials and experts who want this to work often admit that it probably will not. The divisions between Shiite, Sunni and Kurd are too deep, and even within those groups, leadership is fragmented, complicating attempts to negotiate a national solution.

Another option is to accept the reality that Iraq is being pulled apart. Is it better to accept a divided Iraq and reformulate policy to mitigate the damage? This approach typically envisions the eventual creation of three new states out of the old Iraq: A Kurdish one in the north, a Shiite one in the south and a Sunni one in the middle.

The idea of Iraq’s break-up is mostly based on a negative argument that it is inevitable. There is very little positive in this. While some in Washington believe that three separate ethno-sectarian states could be formed fairly easily, this is far too optimistic. Redrawing the borders of Iraq will take years and be very bloody. Nonetheless, reluctantly recognising that this may happen, the US government ought to take this scenario into account in crafting future policies.

Another idea is to create a confederation: Three entities with significant autonomy or even sovereignty that are loosely connected through a weaker government in Baghdad. Each area will have its own budget and security forces. This idea may be the best hope for Iraq — offering the major groups the security and autonomy they require while still providing some of the benefits of belonging to a larger state. However, this would still require negotiation and agreement on many issues that have already been critical to the failure of a federal system.

Iraq is emblematic of the problems with attempting to right the wrongs of history. The country was a useful fiction created to serve the interests of foreign colonial powers. But trying to undo those sins — to redraw maps and forcibly uproot people from their homes and communities — would create new injustices and grievances that would likely drive conflict in the future.

Kerry Boyd Anderson is a writer and political risk consultant with more than 13 years’ experience as a professional analyst of international security issues and Middle East political and business risks.