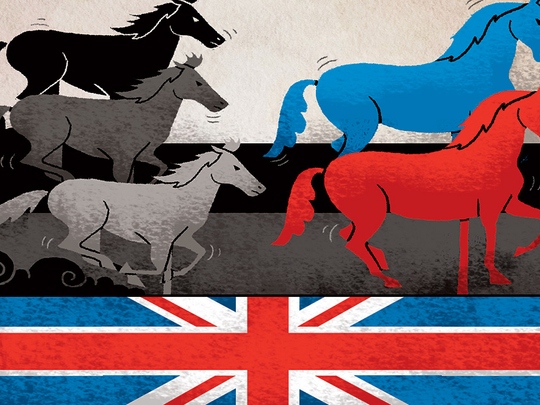

Polls indicate that the UK election result remains too close to call, effectively on a ‘knife-edge’, with the Conservatives and Labour fighting it out to be the largest party and potentially win power. However, the dominant theme of the election is not these two ‘major’ parties, but the rise of third alternatives such as the Scottish National Party (SNP) in Scotland and United Kingdom Independence Party (Ukip) in England.

The remarkable rise of these two parties, and also the Greens too, reflects the current flux in UK politics in which the dominant two party system is giving way, in the short to medium term at least, to a more unpredictable, and uncertain political landscape.

Reflecting this, five parties are currently polling more than 5 per cent of the vote in England (six in Scotland) for the first time ever in UK modern political history.

For much of the post-war period, UK politics has been dominated by the Conservatives and Labour. In the period from 1945 to 1970, for instance, these two parties collectively averaged in excess of 90 per cent of the vote, and also the seats won, in the eight British general elections held in this period.

Yet, from 1974 to 2005, the average share of the vote won by the Conservatives and Labour fell significantly in the nine UK general elections in this period. This has brought about a significant political change that is still unfolding to this day.

It is the Liberal Democrats, to date, which have done most to break the hold of the two major parties on power. From 1974 to 2005, the average Liberal Democrat share of the vote in British general elections was just below 20 per cent.

However, in this current election, it is the SNP which already governs in the Edinburgh Parliament in Scotland; Ukip (a party built around a policy of British withdrawal from the European Union); and the Greens that have had significant impact. Indeed, given the remarkable rise of the SNP in opinion polls, it is clear that the election outcome could be decided, or at least strongly influenced, in Scotland.

Seismic shift

This is because that country, previously an electoral stronghold at Westminster of Labour, appears to be undergoing a seismic shift in loyalty toward the SNP following last year’s landmark independence referendum. This development, which has been described as nothing short of a potential “revolution”, represents a sea change in Scottish politics. And it could have profound implications for the longer-term future of the United Kingdom.

At the last UK general election in 2010, Labour won some 40 of Scotland’s 59 Parliamentary seats (with 40 per cent of the Scottish vote), with the Liberal Democrats securing 11 seats (with 19 per cent of the vote). However, following a surge in support for the SNP since last September’s referendum (with some polls indicating the party has more than 50 per cent of support in Scotland), it could boost the number of seats it has from the current six to what some estimate could be 50 or more.

The importance of this should not be underestimated and has at least two fundamental implications. Firstly, it could threaten, once again, the territorial integrity of one of the world’s longest standing political unions — between England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Thus, although last year’s Scottish referendum was supposed to cement the country in the United Kingdom for at least a generation, there is a significant and growing prospect of a second independence ballot in the next few years.

The prime reason for the transformation in the electoral outlook for the SNP lies in last year’s referendum. That ballot, and the huge debate and interest it awakened in Scotland, means that the issue of how the country is governed (which is the party’s strong suit topic) has become the defining issue in the eyes of much of the Scottish electorate.

Significant gains

A second key impact of the SNP’s rising fortunes in May’s Westminster election is a reduction (but not elimination) of Labour’s prospects of winning a majority in the UK House of Commons. Thus, Labour will probably make significant gains in England on May 7 against the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats, however the impact of these successes could be wiped out by losses to the SNP in Scotland.

It is not just Labour that has been impacted by the rise of third parties. The decline of the traditional two party system makes it much harder for the Conservatives also to secure a majority government in UK general elections. This is despite ‘first-past-the-post’ voting which tends to provide the largest party a significantly larger number of seats in the House of Commons than would be given by a more proportionate electoral system.

To be sure, coalitions and the sharing of power have long been a feature of UK local government and devolved parliaments and assemblies outside of Westminster. However, this same dynamic appears now also to be permeating the heart of the British Government itself.

Until 2010, when the current Coalition Government was formed between Liberal Democrats and the Conservatives, Labour and the Conservatives had won overall majority governments at every election since 1945, except for the brief interregnum between February and October 1974. Yet, as in 2010, it appears most likely that there will a second straight hung parliament in which no one party has close to a majority.

This is, yet again, unprecedented in modern UK political history. And, it underlines the possibility that a second election may be required in coming months, as last happened in 1974.

All of this adds up to the fact that the May 7 election is likely to underline, and potentially reinforce, yet again that the UK’s two party system is giving way, in the short to medium term at least, to a more unpredictable British political landscape. Barring a major late surge by either the Conservatives or Labour, this could be a recipe for significant domestic political and economic uncertainty after May 7 and a possible second election in coming months.

Credit: Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics, and a former Special Adviser in the UK Government