One could be forgiven for thinking the symbolism at the Olympics signalled a hard line from the administration of United States President Donald Trump on North Korea.

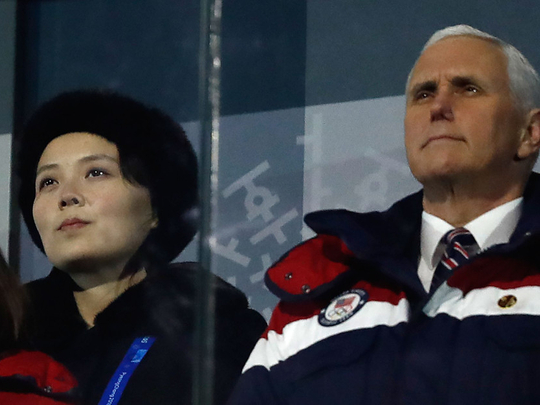

Before the opening ceremony, US Vice-President Mike Pence met North Korean dissidents. At the opening ceremonies, he sat with the parents of Otto Warmbier, the American student who was imprisoned and injured so gravely during his detention that he died shortly after being flown back to the US. In Tokyo, Pence announced that new sanctions would be unveiled soon against North Korea.

But the symbols masked an important concession. Pence recently told the Washington Post’s Josh Rogin that the US was willing to talk with Pyongyang even before the Hermit Kingdom takes any steps ratcheting down the crisis it has created.

That concession averted a break with the South Korean government of Moon Jae-in, who wants to turn the Winter Olympics thaw into more substantive negotiations with the Kim Jong-un regime. It was not a total collapse of the US position either. Pence now says that while the US is willing to talk about talks, the sanctions and other pressure will not abate until North Korea begins making nuclear concessions of its own.

All of that said, most Korea experts concede there is no real chance that talks or financial penalties will persuade Kim to give up his nuclear arsenal. The sanctions might be effective in starving the regime of resources to complete its work on a nuclear weapon (a nuclear warhead for its missiles that would survive re-entry into the atmosphere from space). But as a cudgel to get interim concessions, they are almost certainly futile.

And this brings us back to Pence’s symbolic diplomacy last week. He thanked the dissidents last Friday for their bravery. He said he wanted to make sure the world heard the stories of men and women who suffered torture, amputation and deprivation to escape hell on Earth. “The American people stand with you for freedom, and you represent the people of North Korea, millions of which long to be free as well,” Pence said.

It was an inspiring moment. But raising awareness is the work of journalists and activists. Statesmen have the power to do more. What does America’s broader approach to North Korea offer the people who must endure the Kim family’s rule?

Of course it’s possible to engage in diplomacy and work towards transforming dictatorships without war. Former US president Ronald Reagan was able to negotiate arms agreements with the Soviet Union and still undermine that regime by increasing defence spending, supporting the Polish Solidarity movement and instructing his diplomats to emphasise the conditions of political prisoners.

For the Trump administration, though, all we see is the arms control strategy, what officials now call “denuclearisation”. US pressure is designed to extract a nuclear pause and ultimately disarmament. Where is the strategy for a free North Korea?

While it’s fashionable to say everything has been tried during the last 30 years of nuclear brinkmanship with the Kim family, the element that has been consistently lacking in US policy has been any real effort to aid North Koreans who want to live with dignity. It has been more or less the same kind of formula: Pressure and inducements in exchange for nuclear promises, your regime for your nukes.

Pence’s focus on North Korean political prisoners is a good start, but that’s all it is. Until we see evidence of an American plan to end North Korean tyranny, the US vice-president’s good intentions are hollow, and the dissidents with whom he meets are props.

— Bloomberg

Eli Lake is a Bloomberg View columnist. He was the senior national security correspondent for the Daily Beast and covered national security and intelligence for the Washington Times, the New York Sun and UPI.