Communists the world over, and particularly those in Russia, have time and again propagated the view that there are no stereotypes in Communism or in the gamut of leftist ideology, in general. This is largely based on the belief that each standard-bearer in the leftist movement is unique and cannot be typecast or made to fit into a mould. Taking a dig at such ideological predisposition, a popular joke about Communism and its principal proponents in Russia runs somewhat like this:

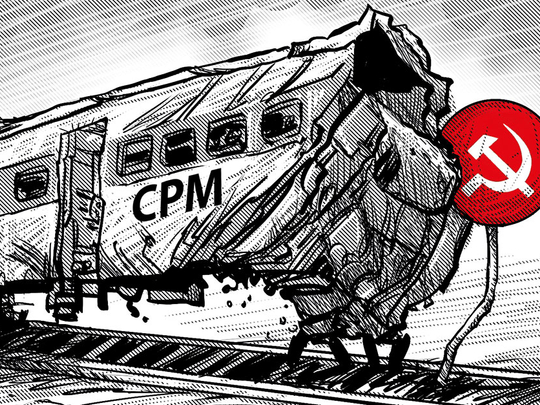

Four Russian stalwarts — Vladimir Lenin, Joseph Stalin, Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev — were once travelling by train. Suddenly, they realised the train hadn’t moved an inch for quite a while. Lenin wondered aloud whether a revolution should be declared immediately, involving the workers and peasants, to make sure the train started rolling. An impatient Stalin peered out of one of the carriage windows and ordered that the driver of the locomotive be shot for noncompliance. To that, Khrushchev suggested that let the tracks from behind the train be uprooted and laid in front instead. Finally, disgusted with these atrocious prescriptions, Brezhnev commented: “Comrades, let’s draw the curtains, turn on the gramophone and pretend that the train is moving!” With the crucial 2019 general elections in India still more than a year away, the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or the CPM — India’s largest left outfit — has shot itself in the foot, yet again, by ruling out support for the Congress party — quite like Brezhnev’s alluded desire to suspend disbelief and indulge in a delusional interpretation of reality.

And this is the third such instance when CPM has allowed dogma and a regimented commitment to political orthodoxy get the better of pragmatism and common sense.

In 1997, when the then chief minister of West Bengal, Jyoti Basu, had emerged as a consensus prime ministerial candidate among a united non-Congress Opposition, it was the CPM Politburo’s stubborn disregard for reality that ruined Basu’s chances — a move that Basu himself later castigated as a “historic blunder”. It was the CPM’s finest hour, when a leftist doyen like Basu in the Prime Minister’s Office could have changed the course of left movement in India, that has largely been confined to the fringes of national politics.

Barring just two instances — offering outside help to Vishwanath Pratap Singh’s minority government in 1989, and supporting a Congress-led United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government in 2004 — the history of left politics in India has largely been a tale of missed opportunities and a frightful abhorrence of practicality. If barring Basu from emerging as the mascot of opposition politics in 1997 was a “historic blunder”, then withdrawal of support from the UPA government over the civil nuclear deal in 2008 was no less a hara-kiri: A gargantuan error of judgement at the behest of Prakash Karat, CPM’s then general secretary. And as if to maintain its consistency with misreading political winds, CPM has done it yet again! Last month, at the party’s Central Committee meeting in Kolkata, two crucial decisions were rubber-stamped that are no less baffling than the “historic blunder” of 1997 or the fallacy of the summer of 2008. Both these decisions were influenced by the politically dominant Karat lobby within the party.

Premature decision

First, it was reaffirmed that party general secretary Sitaram Yechury would not be allowed a third term in Rajya Sabha (Upper House of the parliament). Yechury, whose Rajya Sabha term ended last year, is known to be soft on the Congress. Secondly, it was decided that CPM would not have any electoral tie-up with Congress in 2019.

At a time when a rejuvenated Congress is showing signs of rustling up a powerful antidote to counter the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) challenge, CPM’s decision to treat the Congress as politically untouchable is premature at best and suicidal at worst.

Not allowing Yechury a third term in the Upper House is the corollary to that same pathological inability to let practicality and improvisation tide over a staid copybook that has kept the CPM tied to a dogmatic template for more than half a century.

In four crucial states — Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal and Kerala, that together account for 182 Lok Sabha seats — a coming together of secular-democratic forces is not just a matter of ideological moorings, but an imperative in terms of sheer poll arithmetic. Any split in the opposition vote in these states will allow the BJP to counterbalance a looming anti-incumbency swing in parts of northern, western and central India.

What should be rather embarrassing for the CPM is the way the party has seen a virtual split between the so-called Bengal and Kerala ‘Lines’ — spearheaded by the Yechury and Karat factions, respectively — over the issue of support for or against Congress. The alleged involvement of the son of the secretary of the Kerala unit of CPM in an offshore financial misdemeanour case should do the party’s image no good either. So, was that train in which Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev were seated really moving? India’s CPM would probably want to know something more fundamental: Which ‘Line’ was it on — Bengal or Kerala?!

You can follow Sanjib Kumar Das on Twitter: @moumiayush.