The White House is mixing it up. Usually after commando raids against terrorist targets, the leaks flow like a fine triumphalist wine. We hear just enough detail of high-level secret meetings to emphasise that everything that worked was actually the president’s idea. We may get a photo or two indicating that while considering the raids everyone was looking extremely serious.

But that’s not what happened in the wake of the raids last week. Rather, the response to the US commando operations in Libya and Somalia reminded me a bit of the movie The Right Stuff, when after a post-splashdown screw-up that resulted in the sinking of his Mercury spacecraft, Gus Grissom is denied the pomp and parades that his colleagues had enjoyed.

The raids did not go according to plan. According to reports, the raid in Somalia on Al Shabab encountered heavier resistance than anticipated and presented a much higher risk of civilian casualties than expected.

Post-raid reports indicate that faulty intelligence may have been to blame. The raid in Libya that led the US to grab accused embassy-bombing operative Nazih Abdul Hamed Al Ruqai, better known as Abu Anas Al Libi, produced political blowback ranging from a post-raid statement from the Libyan government that the mission was carried out without its knowledge to the loud criticism of influential Islamic groups in the country that the US had violated Libyan sovereignty to subsequent assertions by Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zeidan that “Libyan citizens should be judged in Libya, and Libya does not surrender its sons”.

The blowback triggered the only orchestrated leaks associated with the raid — comments from the most influential people in Washington, the famed unnamed “senior American officials”, who claimed the US had “tacit approval” for the raid from the Libyans. This wonderful euphemism raises many possibilities. Just what is a diplomatic wink and a nod? Did they raise non-objection objections to ensure the deniability that happened later? Did they simply agree to look the other way? Or did the US government take a page out of Ross’s book from Friends and simply suggest we were “on a break”?

Of course, as the president himself has asserted as recently as his UN General Assembly speech, the US believes that it alone among nations has the right to go “on a break” from international law whenever it suits America. This is the fundamental dimension of American exceptionalism, born of a comment by de Tocqueville about the ‘exceptional’ nature of the American people and more recently made popular by Russian President Vladimir Putin in his controversial New York Times op-ed attacking the American notion that they can play by their own set of rules.

Despite the storm of indignation that Putin’s piece generated from exceptional Americans everywhere, as my friend Tom Friedman of the New York Times might say, just because Putin said it doesn’t mean it wasn’t true.

Exceptionalism is contrary to the spirit of the US Constitution and the ideas that led to the founding of the country. If there is one lesson of human civilisation, it is that equality under the law needs to apply to nations as well as people or else chaos and injustice ensue.

The raids were more damaging not because the outcome of one was unsuccessful, but because the outcome of the other was. If countries feel they can swoop in and snatch up bad guys anywhere, whenever, and however it suited them, the world would quickly fall into a state of permanent war.

It is ironic that President Barack Obama has become the avatar of exceptionalism. As a campaigner and even as a president, he has sometimes seemed resistant to the idea — even when he seemed to embrace it during his first trip abroad after becoming president when he said, “I believe in American exceptionalism, just as I suspect that the Brits believe in British exceptionalism and the Greeks believe in Greek exceptionalism.” It was a dodge designed to drain the idea of its odiousness. That is typically done (by academics as well by politicians like the president) by focusing on the noble values that set us apart.

The defences of this idea founder on the hard truths of what the US justifies with our argument that we are freer or that we promote more equality or whatever other qualities we might list (in a self-congratulatory way) on our national Facebook profile. But then we develop drone programmes that we launch against friends and enemies alike with or without their permission. Or we launch commando raids to grab bad guys. Or we assemble a global surveillance apparatus that knows no limits, violating the sovereignty and privacy of even close allies as if they had no rights at all.

It is one thing to be proud of those qualities that have enabled America to create opportunity and ensure freedom for so many. It is quite another to argue that our success in framing a great legal system on a constitution that legitimately should be a model to the world allows us to ignore the laws and rights of others.

Every nation, the defenders argue, has a right to self-defence. But every nation also faces threats of many sorts. There are bad actors and organisations small and large and even other nations that pose physical, cyber, economic, and other threats to virtually every nation on Earth. Were any threat of any scale allowed to be the justification for the violation of another nation’s sovereignty, the concept of sovereignty would evaporate in a puff of smoke before our very eyes and surely chaos would ensue.

That is why, for all but the most egregious threats, nations must rely on international law and cooperation with other authorities as the mechanisms by which they defuse or manage such threats — grabbing wrongdoers and keeping them from committing further destructive acts. In the wake of the national trauma of 9/11, however, the US fell into a dangerous rabbit hole of dubious logic. Since it had seen one major terrorist attack by one non-state actor that had catastrophic consequences that shook the nation (much as an attack from a sovereign nation might have done), then, the thinking went, all terrorists must potentially pose a similar threat and, therefore, the right to self-defence gives the US a free pass to get ‘all exceptional’ on bad guys or data networks everywhere.

Grave threats justify self-defence under international law. Responding to them is not, therefore, exceptionalism. It is actually the opposite, working within a common set of rules. The trick is defining such threats very narrowly. This error of judgement and logical slippery slope are then compounded by the exceptionalist idea that all other nations and systems are somehow less worthy of respect than ours.

Having been wanted for the Uganda and Kenya bombings in 1998, Al Libi was clearly a very bad actor. But it did not serve US interests to go into a country in which it had ostensibly militarily intervened in order to help restore the rule of law to only then violate those laws and the rights of that country and to send the kind of message that will create more Al Libis than the raid could possibly have taken into custody.

In a seemingly unrelated coda that was also rife with irony, the White House let slip that it is going to withhold certain aid from the Egyptian government because of its origins in a coup and, presumably, its post-coup efforts to restore stability to that country. Set aside for a moment the bizarre timing of this announcement. Set aside for a moment the fact that literally every major ally the US has in the region from the Israelis to the Saudis to the Jordanians to the Kuwaitis to the Emiratis to the Bahrainis surely object to it. Set aside the fact that other aid will keep flowing, thus sending yet another confusingly mixed message to the Egyptians. The decision also underscores that the US is selectively punishing a country that has historically been an ally for trying to reduce the threat posed (and demonstrated) by Islamic fundamentalists while failing to similarly go after those who have supported fundamentalist troublemakers in places like Libya — which is precisely the reason Al Libi was found there. Who are those people we choose not to squeeze? The Qataris come to mind.

During the UN meetings in New York, one smart regional leader said the Qataris were supporting the fundamentalist push in Libya because they saw it, with its hydrocarbon resources, as a potential “milking cow” for the Muslim Brotherhood and similar movements throughout the Middle East. These are the same Qataris that have supported fundamentalists (as have the Turks) in Syria ... and where once again, the US has refused to truly read them the riot act even as it beat up on those going after the fundamentalists.

Exceptionalism is one of the great flaws of US foreign policy exacerbated in the post-9/11 era. But it has been compounded by the mistake of confusing tactics for strategies — of allowing the pursuit of a few terrorists, which generates headlines when successful (and is swept under the rug when not), to distract the US from forming the kind of coherent strategy that advancing American interests in the Middle East and across the Islamic world warrants. The US grabs a terrorist, but inflames the street that is giving birth to the next generation of terrorists. The US punishes an ally for acting extralegally even as it does so as a matter of policy — and fails to realise the terribly mixed and counterproductive message it is sending to those who could help it achieve its greater goals.

As a consequence, while touting a sequence of high-profile wins against individuals or the hierarchy of groups like Al Qaida, the US has watched as new threats have proliferated to the point that they are greater than ever before and its standing has deteriorated to reach new lows. (Ongoing idiocy in Washington on domestic issues doesn’t help.)

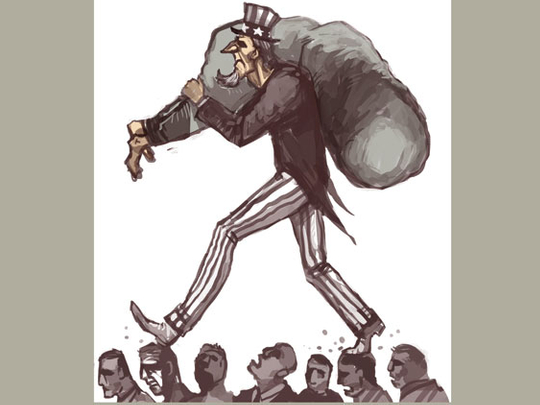

In short, the US has become the incoherent exceptionalist. Not just a giant stomping on the rights of others and seeking to be hailed for it, but one doing so in a way that systematically undercuts the characteristics that have made it great and weakens it at the same time.

— Washington Post

David Rothkopf is CEO and editor-at-large of Foreign Policy. He is the author of Running the World: The Inside Story of the National Security Council and the Architects of American Power.