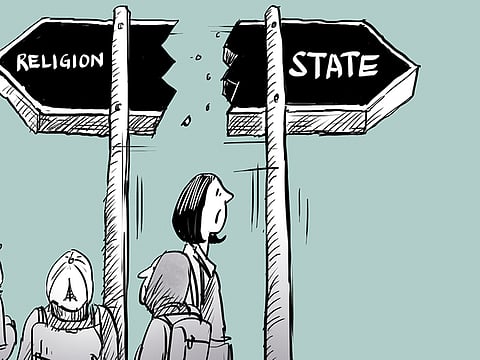

Time to stand up for France’s secularism

Sadly, National Front leader Le Pen’s rhetoric feeds straight into the vision of those who think of the republic as being intrinsically hostile to Muslims

This has been the year the world took notice of France’s identity crisis. After the terrorist attacks at the start and the end of the year gained much international attention, it is now the seemingly unstoppable rise of Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Front that is garnering headlines across the globe. One notable thread in international commentary about France has been the critical scrutiny of its unique brand of secularism: The philosophy of laicite.

But what has been most striking in this coverage is the frequency with which laicite has been both misrepresented and manipulated. French secularism is both misunderstood (by many inside and outside the country) and hijacked (by Le Pen). This is a problem when perceptions often matter more than facts.

Of course, France’s problems cannot be reduced to a question of image. Homegrown terrorism is a reality. The challenges that come with integrating a Muslim population five million-strong are substantial. France’s social fabric has long been weakened by mass unemployment. These issues can be conflated, not least by Le Pen. But because France’s evolution will echo across Europe as a whole, and because the way the country is perceived beyond its borders also feeds back into its domestic situation, it is important to build up a more accurate picture.

Many, especially on the left, believe that the concept of laicite contains a degree of outright hostility towards Muslims. They point to legislation banning headscarves and the burqa. In October, a New York Times editorial gave the impression that French schoolchildren were forced to “choose between eating pork and going hungry”, because the mayor of one town had decided that pork-free options would no longer be offered in local cafeterias.

The reality is more complex. Earlier this year, a young British Muslim woman told me how surprised she had been to discover that she could spend a weekend in Paris without her veil attracting any negative comments. Given common stereotypes in the international press, it must come as a shock to find that 76 per cent of French people hold a favourable view of Muslims (with 24 per cent viewing them unfavourably), as a Pew Research poll revealed last spring — a higher percentage than in Germany (69 per cent) and Britain (72 per cent). Other studies show that mixed marriages have been steadily on the rise in recent years. There is more tolerance than meets the eye in France.

France’s democratic model differs from America’s and Britain’s in that it rejects the notion of multiculturalism, in the sense of a template allowing the state to differentiate between citizens according to their religious or cultural backgrounds. The reasons for this go back to the legacy of the 1789 revolution, and to the 19th-century philosopher Ernest Renan’s definition of French citizenship as “a daily plebiscite”, meaning the decision to live together and be equal. It is a deeply engrained concept. There are no official statistics collected by French authorities on the numbers of Muslims, Catholics, Jews or Protestants in the country.

Earlier this month, France marked the 110th anniversary of its law on laicite, which was voted in after a century of power struggles between republicans and the Catholic church. Laicite is based on three key principles: Freedom of conscience, a strict separation between religion and the state and the freedom to exercise any faith. France, unlike Britain, Germany, Spain or Italy — but like the US — has no established state religion. One big difference from the US is that in France, the state sees itself as the protector of the citizen against potential pressure from religious groups, whereas in the US, religious groups have historically been seen as defenders of the individual against any intrusion from the state.

The French sociologist Patrick Weil, one of the researchers whose work fed into the 2004 law that bans headscarves in state schools, says he started by asking how Muslim girls could be best protected from pressure to wear the veil at a young age. This in itself may be a nod to the rise of a more assertive type of Islam among second and third-generation immigrants, but the way the law was formulated makes sure Islam is not singled out: It bans all “conspicuous religious symbols”, including crosses and kippas (scull caps).

The thinking behind the law is that the state must protect schoolchildren from pressures that might hinder their freedom of conscience once they become adults. It is for the same reason that headscarves are still allowed at French universities, where students are generally over 18 years old.

Another aspect that is often overlooked is that the 2004 law applies only to state schools, not private schools, which are numerous in the country. In 2010, new legislation outlawed the burqa in public spaces. This may have been labelled an illiberal step, but support for the move remains widespread. Interestingly, many moderate Muslim leaders have backed it as a bulwark against pressures from radical Salafism.

Sadly, Le Pen’s rhetoric feeds straight into the vision of those who think of France’s republic as being intrinsically hostile to Muslims. She has cast her party as a key defender of laicite in order to mask the xenophobia and Islamophobia its ideology contains and to reach out to voters who might otherwise have been repelled.

This, of course, is in itself a complete fraud. Her notion of separating religion from anything to do with the state or public affairs does not apply to any other religion but Islam. She wants to ban public Muslim prayers, but said nothing when ultra-traditionalist Catholic groups organised public prayers against abortion, gay marriage or theatre shows they deemed impious.

Part of the problem is that voices that conflate Islam with fanaticism and terrorism are insufficiently confronted by France’s governing elites. Francois Hollande has found few words to reach out to the Muslim population after the November 13 attacks — in the way, say, that United States President Barack Obama did after the San Bernardino shootings.

Finding a way out of the mental web Le Pen has woven around France’s confused debate over national identity is now a huge challenge. But caricaturing France’s model as structurally intolerant does nothing to disable her trap.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox