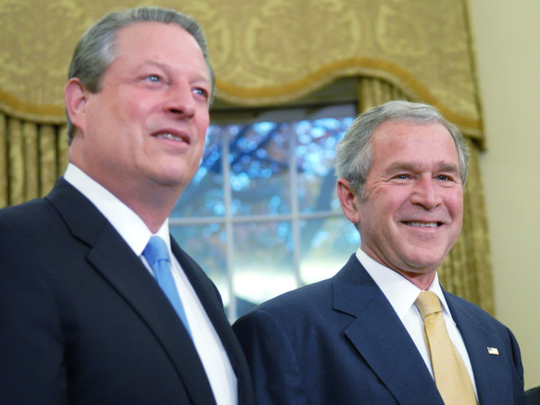

Last Saturday marked the 15th anniversary of the United States Supreme Court’s controversial decision in Bush vs Gore, which put a stop to the recount in Florida and thereby handed George W. Bush the 2000 presidential election. The case excited considerable scholarly argument, along with a partisan rancour that continues to this day. Looking back, however, it’s hard to imagine an outcome that would have left the losing side satisfied — whichever side it happened to be.

Let’s remember the background. First, the “election night” count awarded the state to Republican George W. Bush by 1,784 votes over Democrat Al Gore. An automatic recount, required by state law because of the small margin, determined that Bush had won the state by 537 votes. On November 26, the state’s election authority certified that Bush had won. The Gore campaign protested that thousands of ballots — the so-called undervotes — had been rejected by the counting machines and should have been tabulated by hand. The Gore campaign sued and the Florida Supreme Court, by a vote of 4-3, ordered a manual recount of all undervotes statewide. The Bush campaign then appealed to the US Supreme Court, which heard oral arguments on December 11 and on December 12, ordered the recount stopped, on equal protection grounds, because the state had no clear standard for determining voter intent in tabulating the undervotes.

The vote was 5-4. The dissents were vehement.

The reasoning in Bush vs Gore was terribly weak. As my friend and mentor Guido Calabresi put it, the majority opinion “was unusual though not unique in its total lack of what can be called ‘principle’”. (The reasoning in the Florida Supreme Court was also no masterpiece.) Of course, poor reasoning does not distinguish Bush vs Gore from lots of other controversial Supreme Court decisions. It’s been some while since the justices thought that their work involved persuasion.

Public discussion of the case was mostly risible. I wrote at the time (and still believe) that there was little attention to principle on either side. Democrats and Republicans alike adopted public interpretations of Florida election law that would help their candidate win, and viciously derided those who read that complex statute differently. Dispute that proposition if you wish, but then be prepared to explain the coincidental left-right breakdown on whether Florida law of the time allowed courts to waive the seemingly unambiguous statutory requirement on the date by which recounts had to be completed.

But here’s the really interesting question about Bush vs Gore: Did it actually change the outcome of the election? Because that last recount was never completed, we’ll never know. In fact, we learned a lot about recounts — none of it encouraging.

We tend to pretend that recounts offer magical solutions to election disputes. They don’t. The trouble is that once we go down the recount road, there’s no obvious stopping point. Consider again the Florida contretemps. The first two counts favoured Bush. Let’s suppose that the US Supreme Court had not intervened, and a third recount had favoured Gore. Would that have made him the winner? Why? Why not have a fourth count, or a fifth, or a 50th? There is no optimum number of recounts and it’s hard to explain in advance how we know we’ve reached the precise moment at which justice has prevailed. Most of us, I suspect, believe the counting should continue until our candidate wins.

The one thing of which I am absolutely sure is that had Gore, rather than Bush, won the second count, only to face a Florida Supreme Court order for a third, it would have been the Gore campaign that appealed to the US Supreme Court to intervene and the Bush campaign arguing feverishly in favour of letting the state’s process go forward. No principle was involved on either side, except the principle that says ‘my guy ought to win’.

Not knowing who would have won the third recount has added to the anger and confusion. Although many scholars have studied the problem, the most authoritative tabulation is probably the one undertaken by the accounting firm BDO Seidman (now BDO USA) at the behest of several news organisations. BDO found that under most of the proposed methods of counting disputed or damaged ballots, Bush would have prevailed by several hundred votes. Under one unlikely methodology, Gore would have prevailed by three votes. But no amount of post hoc review is likely to reduce the anger of those who were infuriated by the whole process.

The lesson, I think, is that when the vote is so close that it falls within the margin of error of the count (a figure most of us recognise instinctively), the losing side will never concede defeat. I imagine it must be difficult in the heat of the battle, while resisting the bitter gall of disappointment, to say to ardent supporters: “We lost by a fraction of a percentage point. It’s over.” In the partisan mind, a close election never ends. Even if one grants the accuracy of the official count, Bush won Florida by less than one-hundredth of a percentage point. The margin is too minuscule to be comprehended. Small wonder, then, that to this day, many Democrats insist that Gore “really” won Florida.

Similarly, many Republicans insist that incumbent Norm Coleman “really” won the Minnesota Senate election in 2008, even though a court-mandated third recount certified a victory for Democrat Al Franken by 312 votes — again, just about one- hundredth of a percentage point. (Coleman had won the first two counts.) Notice how the same problem arises. What’s the theory for ending at three? Had a fourth recount favoured Coleman, what logic would have held that Franken could not demand a fifth? Some authority has to establish a stopping point. But from the point of view of the loser, the stopping point will always seem arbitrary. That’s because it always is. And that’s bad for democracy.

The only way to avoid these crises is to win solidly. Thus one can view efforts to increase turnout for your own side in part as efforts to improve the margin of victory so that it “feels” legitimate.

As for Bush vs Gore, the result will never quite “feel” legitimate for many voters. Perhaps that is the price all Americans pay for living in so rigidly divided a nation.

— Bloomberg

Stephen L. Carter is a professor of law at Yale University. He is the author of 12 books, including The Emperor of Ocean Park and Back Channel.