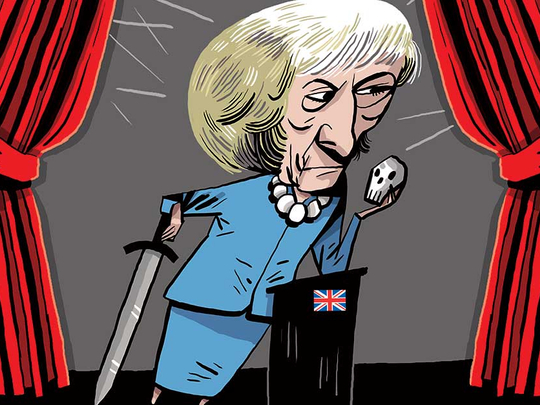

The Roman poet Horace said a play should not be shorter or longer than five acts. German scholar Gustav Freytag defined those acts for the modern age. In her first year as Prime Minister of Britain, Theresa May applied that model to British politics and produced a true drama.

Act I: The Exposition

The protagonist is introduced. It is now hard to remember, yet vital to recall, that May took the Tory crown not by triumph but by default. Every other claimant removed themselves: Former prime minister David Cameron quit after failing over Europe. Boris Johnson quit after failing to convince Michael Gove he was serious about Brexit. Andrea Leadsom quit after failing to realise that common decency demands you don’t try to score points over the fact that someone doesn’t have children. So May found herself playing the role of Fortinbras in Hamlet, arriving after the main players are dead and claiming the throne. The last woman standing found herself before No 10, Downing Street, giving, essentially, a new draft of her leadership campaign speech, where she spoke with well-concealed passion about the “burning injustices” of modern British life and her burning desire to right them. If that agenda’s appeal to the Conservative Party had not been fully tested, it didn’t matter to the wider electorate.

The new prime minister wasn’t flamboyant like Johnson or glossy like Cameron, but she appeared reassuringly solid: A traditional leader for a nation unsettled by the surprise of Brexit. If John Lewis made prime ministers, they would look like May in her first moments in No 10.

Act II: The Rising Action

All new leaders expect a honeymoon period, but May’s sudden dominance of the political landscape was nevertheless remarkable. So too was her use of her new power. This next act could have come from Homer’s Iliad, where all-conquering Achilles is not content with just slaying Hector, but proudly parades his corpse around the walls of Troy. Even as she promised a government and an economy for all, she was seemingly keen to make enemies — and revel in their destruction. She gloried in her seemingly effortless mastery of Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn in the Commons. Their first exchanges at PMQs (questions to the prime minister) left some Tories almost giddy with excitement as her chariot rolled over the Labour leader without slowing.

Internal enemies were dealt with harshly. George Osborne was dispatched with relish, letting it be known she had rejected his request to stay in the Cabinet, and scolded him for not spending enough time with grassroots Tories. The socially liberal Toryism Osborne championed was also rejected. A key scene in this second act was her conference speech denouncing cosmopolitan “citizens of the world” such as Osborne as “citizens of nowhere”.

Powering May’s political juggernaut was her position on Brexit. While colleagues pondered a softer exit where Britain remained in the Single Market and/or the Customs Union, she offered stark clarity: Leaving outright was the only way to meet the public demand for Britain to control its own borders. That view prevailed. Legal challenges, dissent from officials including Britain’s man in Brussels and talk of parliamentary opposition proved to be only minor bumps. She reached her destination in March, invoking Article 50, confirming our departure. She did so having signalled to the European Union (EU) she believed Britain would come to talks in a position of strength, not weakness. “No deal for Britain is better than a bad deal for Britain,” she said in January, a moment that posterity may yet record as the zenith of her career. Patriotic confidence, or misguided hubris?

Either way, May’s offer was enough to unite the Tories behind her and highlight Labour’s lack of clarity on Brexit.

Act III The Climax

It’s fashionable to judge May’s decision to engineer an early election as a mistake, an act of hubristic misjudgement. In truth, there was nothing inevitable about the result. May’s lead in public opinion would have given her a commanding Commons majority, were it not for her own mistakes. The simplest error was indecision. She couldn’t decide who she should listen to. So she signed off a brave and, in parts, radical manifesto that might have made her fine words on the steps of No 10 into governmental action: Its policies were challenging, and might have seen the Tories start to rebalance the scales of power and wealth in favour of the young and poor, and away from the old and affluent. But having approved that manifesto, she couldn’t bear to stand by it and make that bold case. Macbeth made a similar mistake. Having killed Duncan, he is paralysed by doubt: “I will go no more — I am afraid to think what I have done.”

She listened to the campaign advisers who told her to play it safe by ducking debates, keep to the script of Brexit and “strong and stable”; to remind voters their only other option was Corbyn. The more complex mistake is where we approach personal tragedy. A better political saleswoman, a woman comfortable in her own skin, could have made that manifesto the basis for a bold and even inspiring campaign. Yet, having shown daring by calling the election, she reverted to caution and hesitation when it came to the tactical matter of campaigning. Even her now-famous U-turn on the “dementia tax” didn’t have to be so damaging; voters can actually reward politicians who listen. But the painful, stiff way she carried out the manoeuvre (the words “Nothing has changed” will always haunt her) shattered the image of honest solidity. The John Lewis PM made herself look cheap and faulty. If she didn’t know herself, how could voters embrace her?

Act IV: Falling Action

If May’s year has broadly followed the classic dramatic form, the days and weeks after the election verged on the over-dramatic, a coincidence of events that, if this was fiction, may have been rejected as implausible. Less than 48 hours after the result, May was forced to go without her most loyal aides, Fiona Hill and Nick Timothy. The loss of backroom staff might not matter much to the public, but May had previously delegated so much authority to them that their departure rendered Downing Street — and, thus, much of Whitehall — without effective management from the centre. And then the fire began.

The Grenfell Tower fire was, of course, about things more important than politics, but it was also a moment when politicians who aspire to lead must catch the public mood — or fall. May came close to the brink. Whatever the truth of her management of the government response and whatever her true feelings about the fire and its victims, the perception of the PM that week almost undid her: she did not meet victims in public; she did not weep for the cameras. The absence of visible emotion jarred with a nation now comfortable with — and sometimes eager for - the sort of public display of feelings that is inconsistent with her upbringing and temperament. The images of those days will scar May’s image, perhaps forever: The Prime Minister surrounded by a police cordon, talking to firefighters, not families; the prime minister almost running from a church amid angry shouts from the bereaved. A crucial scene of this act was not caught on camera.

Addressing her Downing Street team days after the fire, May did cry, or came as close as she ever will. Think of Coriolanus, once feted as a hero, but woefully unable to win over the plebeians, whose feelings are manipulated by Brutus and Sicinius, the populists of their day. Like Coriolanus, May had made her name as a tough home secretary. But as PM, she saw security become a weakness as terrorist attacks led to debate about her record on funding and supporting the police. The narrative of a failed leader that took hold in those post-election days is strong and all-embracing, poisoning all that she did. So her confidence-and-supply deal with the Democratic Unionist Party was read — as a shameless bribe to bigoted throwbacks — as if Northern Ireland has no right to public money, and as if the people and views its MPs represent should not be heard in London. As Act IV fades to black, Corbyn, once derided as an unelectable shambles, stands on a Glastonbury stage and smiles as thousands of people chant his name.

Act V: The Denouement

Resolution, revelation, or catastrophe? May ends her first year in No 10 poised between those different outcomes. Despite the election and the shattering loss of authority, she remains in office, titular head of a government that can, when it must, muster a Commons majority. Perhaps Tory talk of regicide will turn into action and her colleagues will put this “lame horse” out of their misery — though the absence of an alternative who can command support across the party may save her. In that case, she may stumble on to the end of the Article 50 timetable that would see Britain formally leave the EU in March 2019. That would be painful, but perhaps not hopeless. If recent politics tells us anything, it is that nothing is predictable, so even the improbable cannot be ruled out. Could May claw her way back from the brink to regain some sort of respect from her party and her country as a leader who did not — unlike her predecessor — walk away when trouble came? Since her darkest days after Grenfell, she has set to work with the doggedness that saw her survive the Home Office and stay standing when others fell. Her Commons performances have been steady enough to calm some Tory nerves. She has not sparkled, but nor has she broken. Whatever the audience to this drama may think, and whatever her colleagues may say, the prime minister of United Kingdom, at least, does not believe her story is over. Yet.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2017

James Kirkup is the Daily Telegraph’s executive editor — politics.