Every four years, political leaders have tried to set aside feuds and celebrate the world’s best athletes as they compete for medals and glory — a tradition that harkens back to the first Olympic Games held in Greece some 3,000 years ago.

Apparently, the Brazilians didn’t get the message. Just before the opening ceremonies for the Rio de Janeiro Olympics, a Senate Committee found suspended president Dilma Rousseff guilty of budget fraud and has recommended she be put to trial. Maybe its members took their cue from the Brazilian streets, where tens of thousands of protesters had recently gathered to call for Rousseff’s definitive ouster.

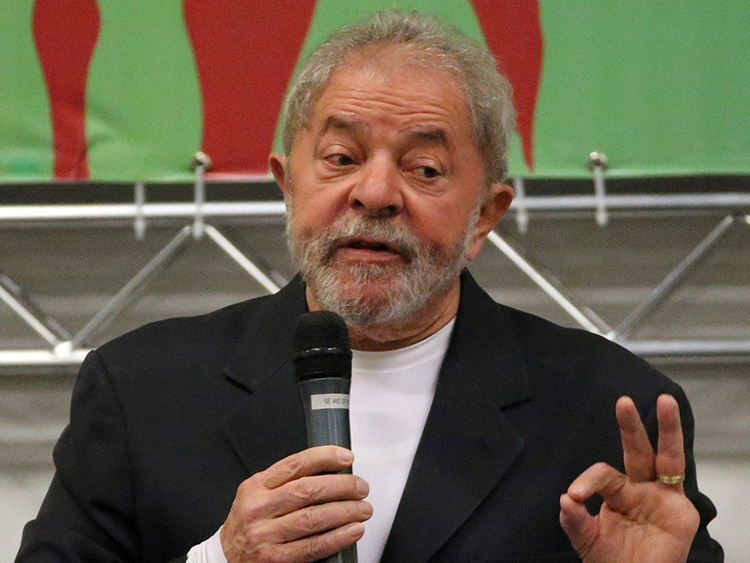

Rousseff will get no help from her mentor, former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. Last week, a federal judge ruled that he too must stand trial in the giant political graft and kickback scheme incubated in his government and which metastasised under Rousseff.

Brazil’s deepening political convulsions are a sign that the drawn-out investigation into corruption at Petrobras is alive and well. In fact, if it were an Olympic event, it would be a marathon with miles left to run: Even after more than two years of detective work, 30 separate police raids and more than 100 arrests, Brazil’s so-called Operation Car Wash is still breaking ground.

To date, Brazil’s biggest corruption probe has taken down dozens of bent business executives, lobbyists and shadowy bureaucrats. Now, new plea bargaining deals are expected to extend that grim harvest deep into Brazil’s political establishment.

Some of the country’s richest construction moguls are expected to come clean about schemes to defraud procurement contracts at the behest of ruling party candidates and legislative allies. Among those reportedly ready to sing are senior executives and former directors at the Odebrecht Group, who may target as many as 100 politicians allegedly involved in pay-to-play deals with Petrobras.

Catching this many crooks was not a foregone conclusion. After all, Italy’s 1990s Clean Hands investigation, an inspiration for Brazil’s cops and prosecutors, lost steam after two years due to public scandal-fatigue and pushback by the country’s clubby political bosses. Many of the new anti-corruption measures fell short, and Silvio Berlusconni vaulted into office on a backlash of shady populism.

To judge by plea bargaining testimony given to police, in which high-ranking officials spoke openly of how to scuttle the Brazilian probe, the Car Wash case also risked similar fate. Instead, those officials are now under investigation for conspiring to obstruct justice.

Lula, apparently, had hoped to evade the law by another escape route. Accused of plotting to buy the silence of a former Petrobras director, he claimed to be the victim of persecution by anti-democratic, “reactionary” forces, led by Sergio Moro, the federal judge presiding over the Car Wash case.

Last week, Lula filed a petition with the United Nations on grounds that his human rights had been violated and demanded that Moro be barred from hearing his case. That complaint echoed earlier calls from Lula’s backers and some friendly jurists that Moro had injected politics into the courtroom and was out to get the former Workers Party icon.

Much to Lula’s surprise, on the same day he filed his appeal to the United Nations, another judge — in Brasilia, 1,400 kilometres from Moro’s courtroom — accepted the federal prosecutor’s charges against Lula and ordered the former president to trial. So much for the one-man, hanging-judge conspiracy against Brazilian democracy.

The case against Lula won’t be decided soon. Nor does Rousseff run the risk of being turfed out during the Rio Games, though that has more to do with Brazil’s crowded legislative calendar than with appeals to an Olympic truce.

Yet in a way, their punishment has already been dished out. The chief of Rio’s Olympic bid, Lula, was convinced the Games would be the coronation of Brazil’s own rise to greatness. Now, neither he nor Rousseff will be in the stands to hail the Olympians. Their moment, like Brazil’s, has passed.

— Bloomberg

Mac Margolis is a writer based in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.