The West should not expect trust from China

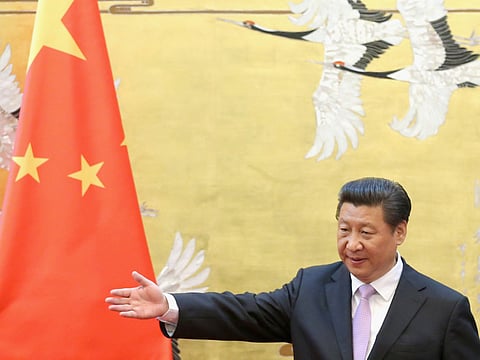

Reading President Xi’s mind has become a staple of international relations

It is an old Chinese adage inherited from Sun Tzu, the philosopher and war strategist who is believed to have lived in the sixth century BC, or thereabouts: If you want to win a hundred battles, you need to understand your adversary, and you need to understand yourself.

Last month, in Washington, a group of foreign policy and security experts discussed China’s rise and the challenges it brings. Much of this discussion, at the event held by the Carnegie Endowment, revolved around trying to read its current leader’s mind. After all, Chinese President Xi Jinping is described as the most powerful Chinese ruler since Deng Xiaoping, who led the country towards reform in the 1980s. The rise of China in recent years has caused frictions within the region; there have been maritime disputes with its neighbours. The change has also caught the West off balance. When Beijing managed to attract several European countries into its Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank last month, the US was irked.

So what is going on in President Xi’s head? Kevin Rudd, the former Australian prime minister, frames the Chinese leader’s priorities this way: First, Xi is obsessed with retaining the central authority of the Chinese Communist Party. That authority is being challenged because of endemic corruption and because of concerns about China’s ability to maintain strong growth. The flipside of this growth is having to deal with pollution levels that can provoke public outrage. Xi, says Rudd, spends “a huge slice of his energy” on making sure that the party stays on top.

Second, Xi wants to re-gear China’s economy from an old (export-led) economic model to a new (domestic consumption-led) model. That is a huge task, especially when growth rates are slowing down.

Third, China wants to continue to seize what its official lexicon calls a “strategic opportunity” to increase its global influence. As a result, China is said to be currently working on lowering tensions in Asia. One sign of that was the recent trilateral meeting in Seoul, between the foreign ministers of China, Japan and South Korea. China’s dispute with Japan over the Senkaku islands will remain a focus of Chinese territorial claims but in a way that will fall short of fostering a crisis. Equally, a breakthrough can no longer be ruled out between China and India on their longstanding land border dispute.

The bottom line is that China has embarked on a new level of global activism. It has overtaken the US as the world’s leading trade power. Today 123 countries in the world have China as their leading trading partner, while the US can count only 64. China is on the lookout for investment opportunities that are not just US treasury bonds. It wants to challenge the mighty dollar, and its currency, the renminbi, now accounts for 15 per cent of global trade transactions.

China’s objective, says Stapleton Roy, a former US diplomat and Asia specialist, is to reach a gross domestic product per capita comparable to the European average by 2049 — the 100th anniversary of communist rule in the country.

China sees the US as trying to oppose its growing international status. Its success with the Asian Investment Bank is a clear sign of the power of its huge currency reserves. But it would be a mistake to think that China believes the US is in decline. China’s demographic trends are not so good and its military power and innovation capabilities are nowhere near as strong as America’s. Xi’s perception is that US power will continue through the 21st century, which means that common dialogue must somehow be found through creative diplomacy. Last November’s joint US-China statement on climate change fitted that picture.

China sees Russia as a declining power that can eventually be transformed into an economic colony.

None of this means there will be much trust in the air. China has a 2,500-year history of strategic thinking driven by a deep distrust of external players. Do not expect a People’s Daily front page proclaiming a new era of Chinese openness towards the West. Nor should Vladimir Putin’s Russia think that it will find an amenable partner in Xi’s China if it continues to turn its back on Europe. China sees Russia as a declining power that can eventually be transformed into an economic colony – reduced to the role of oil and gas provider. China believes it can make strategic gains if Europe and Russia continue to clash.

Reading Xi’s mind has become a staple of today’s international relations and global power-plays. But as I listened to the comments in Washington, I could not help thinking how Sun Tzu’s adage needs to be applied not only to China but to many other challenges the West faces — and how hard that is when nations become inward-looking.

How do you read the minds of key players in the Middle East, including Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) and the Iranian regime? How much energy should we really put into understanding non-western visions of the world, especially those from the global south?

Understanding mindsets is the key to finding ways forward. As a European, one is struck by how the continent’s woes and self-doubts limit its capacity to understand the other — and to embrace global realities.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd