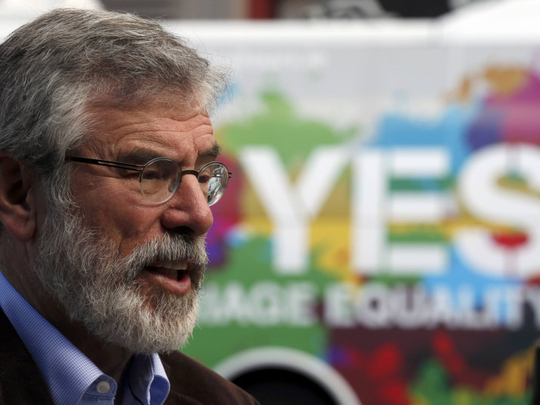

Having been born in Belfast and grown up there, I never thought I would see the day when the Prince of Wales would shake the hand of the Sinn Fein leader. Last week’s handshake between Prince Charles and Gerry Adams at an event in Galway was freighted with meaning. It underlined the fact that, in Ireland, the war is over. It spoke of forgiveness. But away from the cameras and beaming smiles and gestures of reconciliation, it can be a very different story. Forgiveness was a quality not much in evidence in the staunchly republican Markets area of Belfast on May 5.

When I did my four tours of duty in Northern Ireland with the regular Army — I also served with the Special Air Service (SAS) there — the paramilitaries would occasionally undertake a bit of “housekeeping”, the term they used for getting rid of one of their own who had become troublesome or a liability. Anyone thus despatched was referred to as “getting the good news”. Gerry “Jock” Davison “got the good news” outside his house in the Markets in the run-up to the general election. He was shot several times in the head — “nutted” as locals say. Alleged to be the former Officer Commanding of the Markets Provisional Irish Republican Army (Pira), Big Jock had been stood down from operations after the murder of Robert McCartney in a nearby bar a decade ago. McCartney was stabbed and beaten with sewer rods so violently that both eyes popped out. The bar was forensically scoured within minutes and potential witnesses rounded up.

Police statements show that nearly all of the 72 people in the bar were apparently in the lavatories at the time. No one saw anything. But the murder and cover-up were not authorised by the Pira Belfast command. It is believed that Sinn Fein signalled their displeasure. Big Jock heeded the warning, and kept a low profile. Recently he was seen to be becoming more prominent, more outspoken. Time for a bit of “housekeeping”?

Those behind the “nutting” remain unknown. Police have ruled out any dissident involvement and do not believe it was sectarian, so that narrows the field of suspects considerably. The waters may be calmer now, but the ripples caused by the Troubles have still not entirely died away. Adams has to steer a difficult course. Ahead of his meeting with the Prince, he referred to his title as the Colonel-in-Chief of the Parachute Regiment, which he said was “responsible for killing many Irish citizens”, as if the Parachute Regiment was a subversive organisation on a par with the Pira.

Adams may be speaking to the world, but his real message is aimed at his constituency, the republican movement. Its members need to be constantly reminded that the concessions gained after 30 years of war were worthwhile: Parity of esteem, a concept key to the peace process, according to which Irish identity and the Irish language have the same status as British identity and English; and police reform. Bitter dissident republicans would argue that these things are mere window-dressing. They would say that parity of esteem was pretty much already in place and that the police — the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) — were going to be reformed anyway, from a wartime paramilitary outfit into a Britain-style force. They would point out that the war aim — Irish unity — was never achieved. After 30 years, nothing really changed. They do have a point.

In fact, the Troubles ended because the military republican movement was fatally penetrated by RUC Special Branch (SB). Some estimate that one in three members of Pira was an SB agent. Pira was defeated. The overwhelming democratic will of the people both sides of the border was for the status quo and peace. So Sinn Fein took a deep breath and went for the long, long struggle. Get representation north and south of the border, own the intellectual argument and when the time is right, go for unity through the ballot box. If you take that view, some form of Irish unity is inevitable. I suspect the rise of the Scottish National Party (SNP) in Scotland is viewed as a firm endorsement of the strategy first postulated in the mid-Nineties. Crucial to the success of Sinn Fein’s long game is the shedding of its image as a political party inextricably linked to an illegal army ready to murder at the word of command. Part of that strategy of detoxification is a campaign to endlessly draw attention to the perceived injustices of the past and to seek judicial inquiries — and, where possible, international investigations into any shootings by the state. Republicans are not so naive as to try to simply cover their tracks; the idea is to convince voters, especially young ones, that the state was just as bad as the Pira and move on.

Interestingly, this approach is identical to that of the Colombian terrorist group Farc at the Havana peace talks. Ireland or Colombia, it is not an easy thing to bring a violent movement in from the battlefield. The officers commanding need to be kept in their place, and the criminal industries that supported the cause need to be dispersed while remaining profitable.

These can be bitter pills to swallow for those who had dedicated their lives to the armed struggle, those who spent years behind bars. The “peace pill” was sweetened for many regional paramilitary commanders, both loyalist and republican, by the de facto agreement that the working classes of each side were given to them as a dowry. Criminal empires were left relatively intact. Petrol and diesel smuggling still thrive. Counterfeit cigarettes and booze rackets are in vibrant health.

The paramilitaries’ side of the unwritten agreement was that violence would be kept off the streets. If it was to be done at all, it was to be done as sparingly and as discreetly as possible. The dissidents, on the other hand, are desperate to be taken more seriously. They yearn to kill a policeman or soldier. Over the past decade, they have not been without success. Among their victims have been three Catholic policemen and two soldiers, unarmed and eating pizza outside their barracks in Antrim. It is worth noting that aside from the psychopathic mass murderers who head the Real IRA (known in Northern Irish vernacular as the “Cokes” or the “real thing”), the vast majority of the senior membership of that organisation are related to terrorists killed by the security forces, loyalist paramilitaries or as a result of internal feuds. Killing in effect, leads to killing.

In contrast, with the exception of the republican Martin Meehan, no one convicted of a terror-related offence in the Troubles who served a term of more than 10 years ever reoffended. Jail was effective. We should remember that as we face Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) and their apologists. Republican dissidents will continue to be a menace for some time. They may even achieve another murder or two, but, living in the past and blinded by anger, they will eventually fade away. It is of little comfort to victims’ families, but killings by dissidents are a shadow of what PIRA was capable of — and are capable of.

An Irish politician in Dublin once pointed out that while not everybody in Sinn Fein was in the IRA, everybody in the IRA was in Sinn Fein. We are not talking the Lib Dems here. This is a highly focused, disciplined organisation. You do not cross them — if you do, there will be consequences. But Sinn Fein wants power, and is good at getting it and using it. Its discipline is iron, its wealth enormous, and its international alliances complex and effective. If the nice Mr Adams did not think that shaking the Prince of Wales’s hand would make him more electable, he would not do it. The peace, then, is here to stay, but what about prosperity?

Northern Ireland desperately needs jobs, investment and international confidence if it is ever to get the 77 per cent of the workforce employed in the public sector or unemployed into meaningful well-paid jobs that contribute to the economy. The country needs a champion to signal that for most people — with no blood on their hands — the war is over and Northern Ireland is open for business. It fell to a very old friend of Northern Ireland to send that signal. It could not have been easy for the Prince, but the day before he visited the scene of the murder of Lord Mountbatten, “the grandfather he never had”, he shook the hand of the president of Sinn Fein in public. Nothing more need be said.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London, 2015