The problem started when Reed Kennedy tried to book an Airbnb house in upstate New York for New Year’s Eve. “I made a few attempts,” the 42-year-old real estate investor says. “Each time the host would reject my request, but when I went back it was still available for those dates. I realised something was going on.”

Kennedy, who is African American, decided to get a white member of the group to attempt the booking. “She was able to get it immediately,” he continues. “I’d had a profile on Airbnb for three years, validated by email, Facebook and Google, as well as my driver’s licence and passport. She set up a profile with no references, no validations and was able to book immediately. At that point I realised my race was an issue.”

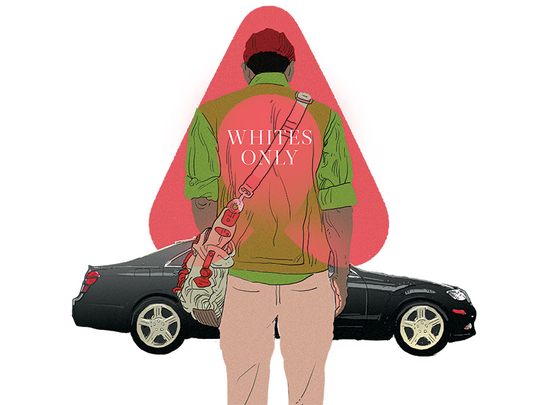

At a time when racial tensions have exploded and racist hate crime is on the rise in the UK and US, discrimination has reared its head in another, more unexpected place: the sharing economy, bastion of feel-good values, sustainability, social responsibility and trust.

“Belong anywhere” promises Airbnb. “Your day belongs to you,” Uber enthuses. “We do chores,” assures TaskRabbit, “you live life.” The messages are bold, slick and utopian. These platforms are a force for good. It’s all about sharing, after all. Except they now find themselves blamed for doing the opposite. Uber and Lyft have been accused of fostering discrimination. A 2016 study in Boston and Seattle found “significant evidence of discrimination”. Rides for men with black-sounding names were cancelled more than twice as often as for other men. Black people faced notably longer waiting times to get paired with drivers. Women were taken on longer routes. Away from the on-demand economy, Amazon was criticised for excluding black neighbourhoods when it launched its same-day delivery offer (it has since expanded its services to correct the problem in several cities).

In December 2015 a Harvard Business School paper revealed that requests from Airbnb guests with African American-sounding names were 16 per cent less likely to be accepted than those with white-sounding names. People started sharing their stories using the hashtag #AirbnbWhileBlack. Articles with titles like ‘The dirty secret of Airbnb is that it’s really, really white’ were written. A New York Times op-ed written by a civil rights lawyer asked: “Does Airbnb enable racism? ” Airbnb finally released a 30-page report in September outlining new non-discrimination policies and systems. CEO Brian Chesky declared discrimination “the greatest challenge we face as a company”.

‘Beyond wildest dreams’

How did Airbnb respond to Reed Kennedy? “Their initial response was to assure me that my race had nothing to do with it,” he tells me. Later he sends me screenshots of their correspondence, in which a member of Airbnb’s customer experience team writes that “the incidents where you’ve been declined by hosts has absolutely nothing to do with your race or ethnicity” and stresses “hosts have the freedom to decline requests for any reason”.

“Airbnb grew beyond its wildest dreams,” Kennedy continues, “and the underlying prejudices in society rear their ugly head in the sharing economy. Now they have to address it. Airbnb will have to take more responsibility from a financial and legal standpoint for the services they provide. The basic concept of public accommodation has to change so that it includes peer-to-peer platforms.”

“There are two main ways that prejudice gets enacted in the sharing economy,” says Tom Slee, author of What’s Yours Is Mine: Against the Sharing Economy. “One is when individuals choose which exchanges to take part in: will an Airbnb host accept this guest, will an Uber driver pick up this passenger? The second is after the exchange, when people rate each other: our prejudices play out in the ratings we give.”

Does Slee think discrimination in the sharing economy could be more insidious than in the real world? “I do, because it is not yet sorted out who has the responsibility to prevent it,” he replies. “Airbnb and Uber routinely claim they are not accommodation or transport providers, so “don’t discriminate” rules don’t apply to them. These claims need to be resisted: Platforms must take responsibility for their service.

Of the major sharing companies I approached, which all have existing anti-discrimination policies on their websites, Uber was “not able to give an interview” and Lyft and TaskRabbit did not respond to my request. Airbnb, which has hired former US attorney-general Eric Holder and former American Civil Liberties Union director Laura Murphy to deal with discrimination, was the only platform that agreed to an interview.

“This is a very new and unsettled area of the law,” Murphy tells me. “When the laws were passed these companies didn’t exist. If anyone had a simple solution for ending discrimination it would have been copyrighted. That being said, I feel Airbnb is committed to this. It has established a permanent team of engineers, data scientists and designers to assess how practices are being implemented. Airbnb has agreed to continuous engagement with civil rights leaders and organisations. That kind of accountability offers a check and balance.”

Critics of the sharing economy argue that what is not being shared is responsibility. Although racism works in the same way in the sharing economy as elsewhere, accountability does not. “Service users are not legally employed by these platforms so they get out of corporate responsibility,” says Slee. “When push comes to shove they’re going to claim it’s not their fault. That’s a challenge because hotels and B&Bs have to abide by laws stipulating they provide a non-discriminatory service. In the case of Airbnb and Uber, who provides this non-discriminatory service? The platform or the individual? And the platform says it’s the individual.”

In April 2016, an individual fought back in Washington DC when Gregory Selden launched a class-action suit against Airbnb for violating the Civil Rights Act of 1964, alleging Airbnb facilitated discrimination. However, Airbnb invoked a private arbitration clause, which means Selden and other users are prohibited from suing the company. “It’s outrageous,” says Ben Edelman, one of the authors of the Harvard report. He says Airbnb’s initial response to his report’s findings “was a kind of denial” and that the company’s non-discrimination policy is “fatally flawed: Too little, too late, and with too much spin on it.”

Fears that discrimination will increase

Meanwhile, sharing economy companies are responding to Trump’s controversial travel ban. Airbnb, which quickly positioned itself as one of the most vociferous corporate critics of the executive order, offered free housing to those affected by it. It also aired a Super Bowl ad celebrating diversity with the tagline “We believe no matter who you are, where you’re from, who you love or who you worship, we all belong”.

Back in the US, while Airbnb data scientists try to come up with an algorithm for ending discrimination, people of colour are finding their own solutions. A year ago Stefan Grant, 28, was staying at an Airbnb house in Atlanta during A3C, the biggest hip-hop festival in America. “We were getting ready [in the morning] and the cops showed up with guns,” the tech entrepreneur says. “The neighbours saw a bunch of black people in the house and thought we were robbing the place.” Grant posted a selfie with one of the officers on Twitter. It went viral and Airbnb got in touch.

Originally Grant was offered vouchers, but when the backlash continued he was flown to Airbnb’s HQ to discuss the issue. “We felt like there was an entire market that was not being catered to or understood,” says Grant. So he came up with the idea of an integrated platform, Noirbnb, catering for travellers of colour. Airbnb, he says, “didn’t want to do it”.

“A couple of months later one of my friends had an #Airbnbwhileblack situation,” Grant continues. “He had a room booked by Airbnb to attend a black tech conference in Miami and when he showed up the host saw my friend, who is a tall black guy, and closed the door on him. They didn’t let him stay.” In the end Noirbnb launched independently, without Airbnb support or integration.

In Tampa, Florida, Rohan Gilkes has launched Innclusive, another Airbnb rival after a blog about his experience of racial discrimination on Airbnb went viral.

Both Noirbnb and Innclusive operate using a different system to Airbnb, which they believe reduces the possibility of discrimination. “We have profile photos and names but we will not introduce the hosts to the information until after the booking is confirmed,” Gilkes explains. “It’s a simple thing to do to avoid unconscious bias and it’s one of the recommendations of the Harvard study.”

Airbnb has so far refused to remove photographs. The photos are one issue. It is also claimed that the ratings systems Uber and other sharing economy platforms rely on to build trust enable discrimination. “Ratings give us our reputation,” Slee tells me. “But this is not neutral. In a society with racist elements that’s going to show.” What has been termed algorithmic management begins to look less like economic empowerment and more like the Nosedive episode of Black Mirror. “Ratings shape your experience on the platform,” Slee continues. “At the extreme you can be deactivated on Uber if your ratings go down.” Deactivated, in tech speak, means fired.

The week before we speak, Edelman’s own Airbnb account had been suspended. Murphy tells me this is because “no one is allowed to create multiple aliases” (he had created other accounts to monitor discrimination, which were suspended during the study). His personal account has since been reinstated. Edelman says this only happened after the Guardian reported on the story. Previously, when he contacted Airbnb “they didn’t reply and they didn’t reinstate [the account].”

As for Gilkes, he no longer uses Airbnb. “It’s kind of traumatising,” he tells me. “It messes with you mentally. I would not put myself through that.” And Kennedy has yet to successfully book a single Airbnb stay, bar one exception. “I got a gift certificate from Airbnb [after complaining about experiencing discrimination] and I was definitely going to use that. I tried to in New York last year but nobody would rent to me.”

In the end, Kennedy had to use an instant booking. “Ironically the host was an African American man,” he notes. “He was probably using instant booking for the same reason as me.”

— Guardian News and Media Limited

Chitra Ramaswamy is a freelance journalist based in Edinburgh. She is the author of Expecting: The Inner Life of Pregnancy.