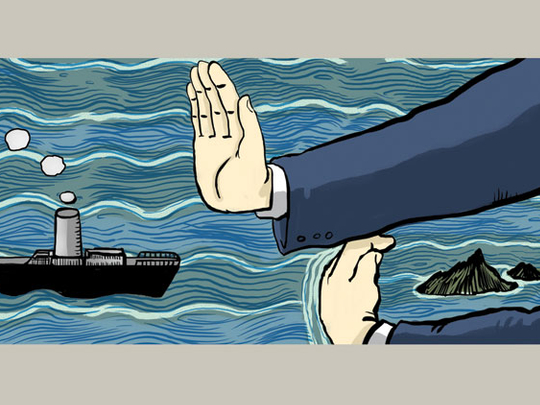

These are no ordinary times in East Asia. With tensions rising from conflicting territorial claims in the East China and South China seas, the region increasingly resembles a 21st-century maritime redux of the Balkans a century ago — a tinderbox on water. Nationalist sentiment is surging across the region, reducing the domestic political space for less confrontational approaches.

Relations between China and Japan have now fallen to their lowest ebb since diplomatic normalisation in 1972, significantly reducing bilateral trade and investment volumes and causing regional governments to monitor developments with growing alarm. Relations between China and Vietnam, and between China and the Philippines, have also deteriorated significantly, while key regional institutions such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) have become increasingly polarised.

In security terms, the region is more brittle than at any time since the fall of Saigon in 1975. In Beijing, current problems with Tokyo, Hanoi and Manila are on top of the mind. They dominate both the official media and the social media and the latter have become particularly vitriolic.

They also dominate discussions between Chinese officials and foreign visitors. The relationship with Japan in particular is front and centre in virtually every official conversation as Chinese interlocutors probe what they identify as a profound change in both the tenor of Japanese domestic politics and the centrality of China within the Japanese debate.

Beijing does not desire armed conflict with Japan over territorial disputes, but nonetheless makes clear that it has its own red lines that cannot be crossed for its own domestic reasons and that it is prepared for any contingency.

Like the Balkans a century ago, riven by overlapping alliances, loyalties and hatreds, the strategic environment in East Asia is complex. At least six states or political entities are engaged in territorial disputes with China, three of which are close strategic partners of the US.

There are multiple agencies involved from individual states: In China, for example, the International Crisis Group has calculated that eight different agencies are engaged in the South China Sea alone.

Furthermore, these territorial claims — and the minerals, energy and marine resources at stake — are vast. And while the US remains mostly neutral, the intersection between the narrower interests of claimant states and the broader strategic competition between the US and China is significant and not automatically containable.

Complicating matters, East Asia increasingly finds itself being pulled in radically different directions. On the one hand, the forces of globalisation are bringing its people, economies and countries closer together than at any other time in history, as reflected in intraregional trade, which is now approaching 60 per cent of total East Asian trade.

On the other hand, the forces of primitive, almost atavistic nationalisms are at the same time threatening to pull the region apart. As a result, the idea of armed conflict, which seems contrary to every element of rational self-interest for any nation-state enjoying the benefits of such unprecedented regional economic dynamism, has now become a terrifying, almost normal part of the regional conversation, driven by recent territorial disputes, but animated by deep-rooted cultural and historical resentments.

Contemporary East Asia is a tale of these two very different worlds. The most worrying fault lines run between China and Japan, and between China and Vietnam. Last September, the Japanese government purchased from a private owner three islands in the Senkakus, a small chain of islands claimed by both countries (the Chinese call the islands the Diaoyu).

This caused China to conclude that Japan, which had exercised de facto administrative control over the islands for most of the last century, was now moving towards a more de jure exercise of sovereignty.

In response, Beijing launched a series of what it called “combination punches”: economic retaliation, the dispatch of Chinese maritime patrol vessels to the disputed areas, joint combat drills among the branches of its military, and widespread, occasionally violent public protests against Japanese diplomatic and commercial targets across China.

As a result, Japanese exports to China contracted rapidly in the fourth quarter of 2012, and because Japan had already become China’s largest trading partner, sliding exports alone are likely to be a significant contributive factor in what is projected to be a large contraction in overall Japanese economic growth in the same period.

In mid-December, Japan claimed that Chinese aircraft intruded Japanese airspace above the disputed islands for the first time since 1958. After a subsequent incident, Japan dispatched eight F-15 fighter planes to the islands. While both sides have avoided deploying naval assets, there is a growing concern of creeping militarisation as military capabilities are transferred to coast guard-type vessels.

While the “static” in Japanese military circles regarding China-related contingency planning has become increasingly audible, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who took office in mid-December, has sought to moderate his public language on China, apparently to send a diplomatic message that he wishes to restore stability to the relationship.

This was reinforced by a conciliatory letter sent from Abe to Xi Jinping, China’s new leader, on January 25 during a visit to Beijing by the leader of New Komeito, the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s coalition partner. This has been publicly and privately welcomed in Beijing, as reflected in Xi’s public remarks the following day.

Beijing’s position is that while it wants Japan to formally recognise the existence of a territorial dispute in order to fortify China’s political and legal position on the future of the islands, it also wishes to see the Senkaku/Diaoyu dispute managed in a manner that does not threaten regional security, which would undermine the stability necessary to complete its core task of economic reform and growth.

There may therefore be some softening in the China-Japan relationship for the immediate period ahead, though diplomatic and strategic realities appear to remain largely unchanged.

The intensity of Abe and Japanese Foreign Minister Fumio Kishida’s unprecedented mid-January diplomatic offensive, involving visits to seven East Asian states, demonstrates that the temperature between Beijing and Tokyo remains high — just as the late January statement from Tokyo on the establishment of a special Japanese Coast Guard force of 12 enhanced vessels and 600 servicemen specifically dedicated to the Senkaku theatre underlines the nature of the challenges lying ahead. The problem is that neither side can afford domestically to be seen as retreating from current positions.

China believes that Japan has altered the status quo; Japan believes it has no need to budge because there is no sovereignty issue in the first place. All of this means that both sides remain captive to events on the high seas and in the air — events that could quickly spiral out of control.

To prevent this from happening, both sides will obviously need to maintain their public political positions for domestic reasons, while both will need gradually and reciprocally to de-escalate the deployment of maritime and air assets.

This will need to be done according to a schedule negotiated by an intermediary or though their own back channels. If such back-channel negotiations are not already under way (and there is some evidence they may be), then it is in the interests of both sides to get the ball rolling.

Japan should not install any equipment or station any personnel on the islands, as has been discussed from time to time in Tokyo, as this would inevitably result in further retaliatory action from Beijing, with every prospect of generating a further crisis.

If these steps could be taken and the situation then stabilised, perhaps longer-term consideration could be given to inviting an appropriate international environmental agency to exercise environmental management responsibilities on and around the islands, where, by informal agreement, national vessels would not go.

By contrast, territorial claims in the South China Sea are even more complex. According to US agencies, Chinese officials have claimed the sea contains proven oil reserves as high as 213 billion barrels (10 times that of US reserves, though American scientists are more sceptical) and 25 trillion cubic metres of gas reserves (roughly the total proven reserves of Qatar). The South China Sea also accounts for some 10 per cent of the world’s annual fisheries catch.

The region is already the scene of deeply disputed exploratory activities for deep-sea energy resources. Fisheries are also already the subject of multiple physical confrontations between vessels. Furthermore, unlike the Senkaku/Diaoyu, many islands in the South China Sea are already occupied, garrisoned and home to naval bases.

Six states plus Taiwan have disputed territorial claims in the area, though the largest overlap by far is between China and Vietnam. The two states have already skirmished over their conflicting claims, in 1974 and 1988; they also fought a major border war in 1979.

One senior Vietnamese neatly described the Sino-Vietnamese relationship in May 2011 by saying: “The two countries are old friends and old enemies.” It is also clear that the Chinese today possess considerable economic leverage over Vietnam, to the extent that one senior Vietnamese official candidly remarked recently that China could simply wreck the Vietnamese economy if it so chose.

It will be wrong, however, given ancient resentments, that economic dependence will automatically constrain Vietnamese diplomatic or even military action in relation to the South China Sea. The China-Vietnam relationship has soured since Chinese ships severed the seismic cables of Vietnamese exploratory vessels in May 2011 and again in December 2012.

According to Reuters, Vietnam subsequently stated that as of January 2013, it would deploy civilian vessels supported by marine police to stop foreign vessels from violating its waters, while India, Vietnam’s partner in some of the explorations, indicated it would consider sending naval vessels to the South China Sea to protect its interests.

Meanwhile, China’s Hainan province announced that starting this year, provincial maritime surveillance vessels will begin intercepting, searching and repelling foreign vessels violating Chinese territorial seas, including the disputed territory. These various statements concerning new and radically conflicting procedures for the interception of foreign vessels set the stage for significant confrontation in the year ahead.

Vietnam and China appear to have set themselves on a collision course and those who monitor this relationship closely fear a repeat of those earlier armed conflicts. To prevent further escalation, Beijing and Hanoi need now to step back from the edge.

They should agree to prioritise development of, and agreement on, the long-awaited code of conduct between Asean and China on the South China Sea, including the joint development of energy projects.

Both governments should identify a single project in an area where both sides claim sovereignty and begin the practical negotiation of a joint development regime. If this is too difficult, then both sides can consider the development of a joint fisheries project in a single defined area, as this will further sidestep sensitive sovereignty issues more acutely connected with resource extraction regimes.

In other words, rather than wait for the conclusion of a complex diplomatic negotiation over the final text of the code of conduct, they should start to build trust by cooperating on a real project.

If this approach succeeds with China and Vietnam, similar joint development projects can be developed with the other claimant states. None of this may work. Nationalism may prevail. Policymakers can simply allow events to run their course, like they did a century ago.

In his recent book, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914, historian Christopher Clark recounts how the petty nationalisms of the Balkans combusted with the great-power politics and failed statesmanship of the time to produce the industrial-scale carnage of First World War.

This was a time when economic globalisation was even deeper than what it is today and when the governments of Europe, right up until 1914, had concluded that a pan-European war was irrational and, therefore, impossible.

I believe a pan-Asian war is extremely unlikely. Nonetheless, for those who live in this region, facing escalating confrontations in the East China and South China Seas, Europe is a cautionary tale very much worthy of reflection.

Kevin Rudd is the former prime minister and foreign minister of Australia.