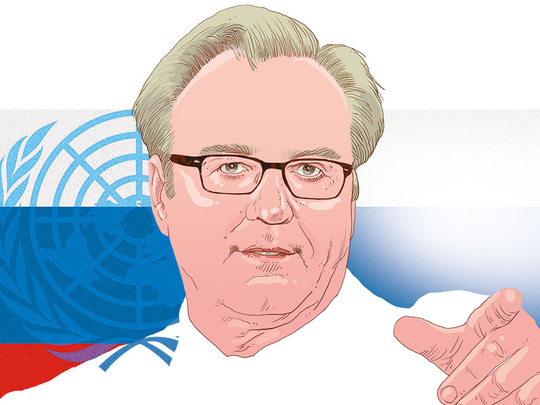

‘The Man Who Saved the World’ is a documentary movie that Ambassador Vitaly Churkin insisted on lending me several months ago after we had a neighbourly dinner at his house one night. Russia’s Ambassador and Permanent Representative to the United Nations was many things to many people. To me, he was not only a diplomatic grandmaster, but he was also my neighbour on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, where the UAE and Russian town houses look into each other’s backyards, and a colleague from an important country to the UAE, and in the past couple of years — after a few visits to our annual Sir Bani Yas Forum — a friend.

This movie was one of Vitaly’s favourite films. It had been given to him by a former US Secretary of Defence, and was a true story — a long kept secret — about one terrifying night at the height of the Cold War, in September 1983. The United States and the Soviet Union came very close to nuclear annihilation because of a malfunction in the Soviet early-warning system. At a top-secret “watching” station outside Moscow, beeping red alerts erroneously indicated that there were five incoming missiles from the west coast of the United States heading towards the Soviet Union, in what looked like a pre-emptive nuclear strike by the Americans.

Tensions were already heightened by the shooting down of a Korean Air Lines flight earlier that month carrying 269 passengers, many Americans among the victims, which created a plausible context for an escalation. Vitaly was 31 at the time, a second secretary at the Soviet Embassy in Washington, and the plane incident was one of the first crises he had to deal with in his diplomatic career. While facing a “hostile anti-Soviet crowd” at the Washington memorial, he says he first learnt the need to develop a tough skin as a diplomat. He credited being able to handle any difficult situation later on in his career because of that early experience.

The documentary homes in on the unsung hero of that fateful night in 1983, Lieutenant-Colonel Stanislav Petrov, who was on duty. The fate of the world rested in the hands of a mid-level Russian military officer, who had a 15-minute window to decide whether to launch a counter-attack that would have annihilated a sizeable amount of the US population, or wake his commanding officer to tell him that he thought there was a mistake and they should not retaliate. In a tense recap of his movements, the film shows him thankfully choosing the latter course of action.

I was gripped by the story and how close we had come to the end of the world that night, unbeknownst to many until years later. But I was also moved, as I think Vitaly was, by the story of one ordinary man and his brave stand when he found himself at the centre of a storm — an act of cool-headed restraint that was not even recognised, because the Soviets had kept the whole incident secret. In the words of the protagonist Stanislav, a gruff military man with little patience for emotional analysis of his own bravery: “I am not a hero, I was just at the right place at the right time.”

Sudden passing

Ambassador Churkin’s sudden death one February morning in New York, where he had served as Russia’s Permanent Representative to the UN for nearly 10 years, shook the diplomatic community. I was chairing a session of the UN General Assembly when approached by the Russian Deputy Permanent Representative, who asked me to make the announcement of Vitaly’s passing to our colleagues in the hall. I did so in some shock, unable to absorb it, as we stood to observe a moment of silence and respect for a man who had become almost as institutional as the UN building and the Security Council chamber itself.

On my mind were his warm and lovely wife Irina, whose genuine interest and empathy for the UAE undoubtedly helped develop our relationship with her husband, and of course their two children, Maksim and Anastasia, both charming, smart and incredibly well-rounded young adults.

I remember Vitaly calling me last December in great excitement, telling me he wanted me and my husband Omar to attend his wife’s birthday party that he was throwing for their friends at the Russian Mission’s guest house on Long Island. The guest list was made up of close friends and we were truly honoured to be considered part of that group. During a fun evening of speeches mostly in Russian, a live band, and a lot of emotion and tears (as is apparently customary at a Russian birthday dinner party), I offered a tribute to Vitaly and his family — of how close they had become as friends of the UAE and our leadership.

This was attested to after his passing by the cable sent by His Highness Shaikh Mohammad Bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the UAE Armed Forces, to President Vladimir Putin on the untimely passing of a “seasoned diplomat”. I reflect now on the numerous occasions I called on Vitaly when asked by Shaikh Abdullah Bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, to brief him on our views on regional developments, and Yemen in particular, and I remember how intently he used to listen and try and understand our perspective.

Assurances

He used to tell me that where the UAE was concerned, we could expect the closest collaboration from Russia. And he came through for me several times when we needed support for various issues on the Security Council. I still today expect to bump into Vitaly in the corridors outside the UN, with a ready joke for me or a smile, an offer of dinner or an earnest conversation about Yemen or Syria. At dinner at the Sir Bani Yas Forum last November, he told me: “It’s not easy always being required to be the villain in the play every day, walking into the UN in that role that everyone sees you in can wear you down.” Perhaps an eerie echo of the deterioration of Soviet-US relations in the 1980s when Ronald Reagan called the Soviet Union “the evil empire”, it struck me that night how exhausting the persona he was expected to play actually was, day in and day out. I feel fortunate that the UAE had built a nuanced and personal relationship with Vitaly as an individual at the highest levels — and perhaps became closer to his country because of it. He was so honoured during his visit to the UAE that Shaikh Mohammad Bin Zayed received him. He told me afterwards how much he valued the richness of their discussion, and the extraordinary leadership and vision of the UAE. It was a place he had chosen to come to for his last vacation with his wife because of his affinity for our country and even a place he could perhaps imagine retiring in one day.

My first meeting with Vitaly was in the imposing Russian Mission to the United Nations, a throwback to another era. Our conversation felt like a game of chess with polite manoeuvres back and forth at the opening of our discussion, with a grandfather clock tick-tocking in the background as we sipped lemony tea. I remember seeking his advice on approaching the UN, which he gave generously but formally. At the time, I thought that I had my work cut out for me to develop the relationship into the warm and respectful one it would eventually become.

Multi-layered, complex individual

It took a while to break down that exterior he always had to hold up to his colleagues, knowing that every word he said about any issue would be repeated and reported back in notes to capital. He had clearly developed over the years the ability to move between skins, to present only glimpses of the warm, witty inner personality that I was to discover later — or the ready sense of fun waiting to be drawn out. To me, he was a multi-layered and complex individual. We could have frivolous discussions about celebrity-spotting in New York, the show The Americans of which we were both fans, his early life as an 11-year-old boy actor in a famous Russian movie about Lenin, his little-known passion for speed skating, his love of American movies, as well as deep discussions about my region and Russian foreign policy.

A diplomat who had served as both the last spokesperson for the USSR Foreign Ministry and the first spokesperson for the Russian Foreign Ministry after the Soviet Union had dissolved, he was a man who had lived through a deep sweep of history. He was a patriot who defended his country with commitment, but also worked tirelessly behind the scenes to bridge the divides and find a common path forward. I saw this up close many times in his working relationship — and friendship — with Ambassador Samantha Power which was often — and wrongly — projected in the media as a black and white enmity. I saw how they were able to move past diplomatic postures to try and do something positive in their respective roles; for peace and security and ultimately for the UN and their two countries’ places in the world — which they both so fervently believed in. I saw it when we would lobby for something in Moscow through our ambassador, and the reply that would come back from the Russian foreign ministry was — “Vitaly is in charge of this decision or that — just talk to him.”

Following Vitaly’s passing, I have been re-watching the last lectures he probably ever gave on global affairs, the UN, his experience of history and the meaning of diplomacy, which were recorded when the UAE was fortunate to host him last November at the Emirates Diplomatic Academy.

He gave an extraordinarily rich lecture during which he described the 1980s to our young diplomats as “an incredible era” that is hard to describe today, but that he remembered vividly as a young diplomat in Washington: “Nearing a hair-trigger situation when a nuclear strike was possible between both countries... it’s difficult for us to imagine fortunately now, that kind of mindset... I’m often asked — are we back in the Cold War now, the way it existed before and my answer is definitely NO... because for us it’s impossible to imagine a situation today where we prepare for an all-out nuclear war with each other... knowing it would result in total annihilation of our civilisations and in fact global civilisation.”

The 31-year-old Vitaly Churkin would not have known during that difficult first posting in Washington that an unknown lieutenant back in Moscow was a key reason that mutual annihilation did not in fact happen during that pivotal month in 1983, and perhaps many more times subsequently while he served his country faithfully abroad.

The man I knew, who lent me the movie and told me to watch it 30 years later, was clearly in awe of how closely he had touched the fabric of history at that time. Like Lieutenant-Colonel Stanislav Petrov, Vitaly was a man who did not see himself as a hero. But from my time watching him in New York, I believe he was a man who worked hard to do some good. To me, Vitaly Churkin epitomised what great diplomacy can look like as an art form — when attached to a deeper sense of purpose to find that sometimes elusive, but incredibly important, common ground among nations.

Lana Z. Nusseibeh is the Permanent Representative of the United Arab Emirates to the United Nations.