Islamists of various political shades are now in power in a growing number of Arab states. They are a new reality that everyone will have to deal with, and therefore seek to understand. The challenge is that most of these parties have been in opposition for decades under long-established military presidencies, and during these years they did not hone their manifestos to prepare for power, so they did not come to power offering detailed economic policies.

As opposition forces, they specialised in getting their deep emotional appeal out to the masses of the people, using religion as a way to attract and gain people’s trust. For example, during the long decades of Hosni Mubarak’s domination of Egypt, as hospitals and schools failed, the Islamist movements provided their own alternatives, often working to a very high standard, and establishing a significant place in people’s lives.

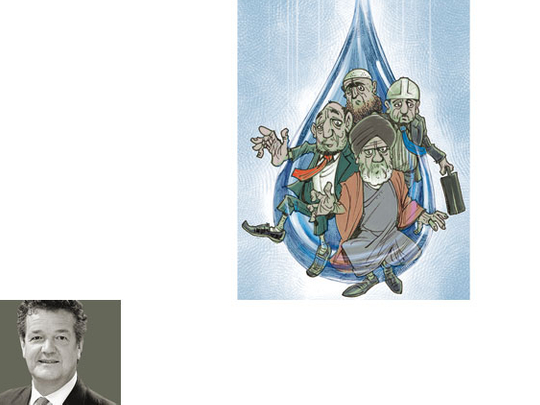

But this effective tactic in opposition does not translate into clear plans in government. The broad headline ‘Islamist’ does not add up to a coherent or single regional or economic agenda. While there maybe some very broad consensus on what Islamist governments seek socially, Islamism describes a movement including many shades of political action and parties vying for power.

And when in power, these wide social principles face the reality of government. Much of what a government does day-to-day is to manage and develop the infrastructure of a state, so that people can get on and make their own lives. There is nothing particularly Islamic about delivering 24-hour-a-day electricity to every house in a country, or ensuring the supply of clean water for the whole population, or that the sewerage system is working. The core principles of Islamist parties do not offer much guidance on whether economic global openness or national protectionism is better. There is no automatic allegiance to socialism or capitalism, so the all-important governmental task of offering its people a safe and growing economy in which individuals can invest and seek to improve their lot, is very much open territory for the new policymakers who have just come to power.

In Egypt, President Mohammad Mursi has wrested power from the military, but has yet to make obvious what economic policies he will implement. He will benefit from an upturn in GDP thanks to the increased political stability offered by his government, leading to foreign investors coming back to the country. One useful indication of a commitment to more open market policies is the announcement this week by Egypt’s oil minister that he plans to reduce Egypt’s legendary huge fuel subsidies.

In Tunisia, the economic downturn which happened during the drama of the revolution has persisted, and the interim government has been criticised for getting into too much debt. However, a Qatari project to build an oil refinery may be an indication of investment interest and a future up-turn. But the economy is not everything. In the Arab region, there is huge concern that the parties that are now in power in many Arab states move decisively away from their previous call for Islamic revolution across the region, which either they or their fellow travellers were supporting only a few years ago. There is a vital difference between those Islamist political parties that are willing to work within a constitution, and those that continue to seek violent change across the region.

And this is a very important test of the new Islamist governments. Now that they have been elected into power they are being forced to demonstrate their commitment to pluralism. This is a new challenge they did not plan for when they were in the opposition, but one that the whole region is watching carefully. For example, this means it is important how Mursi’s government develops new laws in Egypt. It is natural that the whole region is watching to see how he manages to kick-start the economy and develops laws which welcome foreign investment, much of it from the Gulf. But he is also being carefully looked at as to how he might implement any codes of Sharia, and whether such changes might impact the whole population including more secular-minded Muslims and the large Coptic minority.

It makes as much sense to talk of a single Islamist agenda for all the Islamist parties in power as it does to speak of one ‘democratic’ agenda in Europe. The story of the next few years will be how today’s Islamists become a more nuanced spread of political parties. There is already a division between the Brotherhood and the Salafists. This is only a small indication of the huge range of political offerings that have yet to emerge from the Islamist movement.