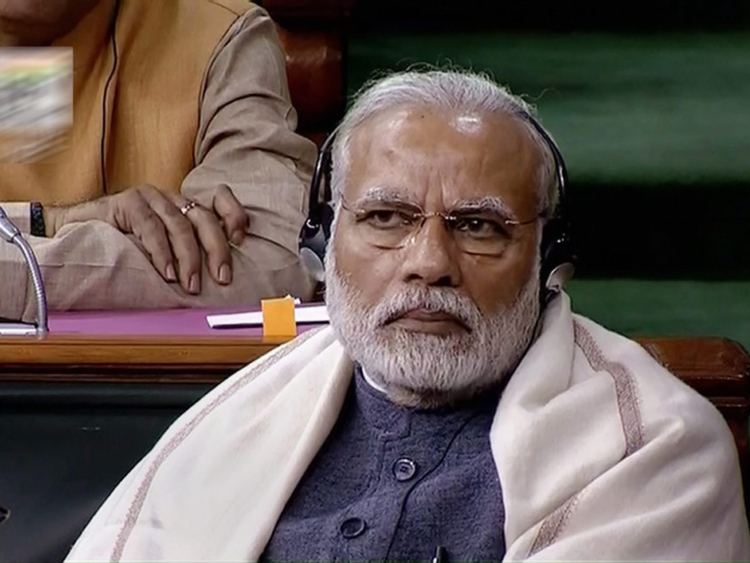

Last week, in the Indian parliament, mythology, as is the present wont, was once again put to good use. Prime Minister Narendra Modi was making a speech, typically flowing and grandiose. In passing, he made a charitable claim on behalf of one of the most controversial identity cards in all history: The Aadhar card, which the Government of India seeks to link with just about everything.

As Modi began to praise the efficacy of the Aadhar card, Renuka Choudhury, an articulate and no-holds barred Congress (the Opposition party) member of parliament, began laughing loudly. If you would watch the clip, it is a rather long, peeling laughter, and it would be clear that she actually was enjoying the situation; and she clearly believed that the prime minister’s claims needed to be laughed out of court.

Well, it would be difficult to laugh like that and be not admonished.

The Rajya Sabha (Upper House) chairman and India’s Vice-President, Venkaiah Naidu, reprimanded Renuka for her “unruly behaviour”. The video shows him genuinely agitated. But Modi, showing political presence of mind, suggested that Renuka continue with her laughter, as he had not heard such hearty peels since the Ramayana TV series in the 1980s.

Modi was referring to Surpanakha, the little sister of the evil king Ravana — whom Lord Rama slays in the story. According to one (the Brahminical Valmiki) version of Ramayana, Surpanakha (the One with Long Nails, in Sanskrit) transforms herself into a beautiful woman and tries to seduce Rama, who rather has fun in passing her off to his brother Lakshman, and who finally chops off her nose and ears, and sends her back to Ravana. This incident is one great reason why the war between Rama and Ravan was triggered. When Ravana kidnapped and brought the chaste Sita to his palace, the one person who most gloated over her misfortune was Surpanakha.

Modi had won the day in parliament, as the male-dominated ruling party benches thumped their desks in merriment. Outside, in real time, the comment had triggered a social media storm, with progressive women and their male counterparts attributing a chauvinistic flavour to Modi’s comment.

As an observer, I found it hard to sympathise with Renuka. Assume you are in a board meeting, or even in an editorial meeting, or, well, just about any serious discussion and then to laugh the Renuka laughter is to say not only one doesn’t believe in the speaker’s claims, but that one does not attach any value to norms that guide a democratic discourse. A titter or two, may be. But peels of loud, seemingly unending laughter?

But the civil society was not having any of it. The incident was no longer about the great Aadhar claims of the prime minister, but whether a woman could laugh at a man. There was a flood of essays and links to subjects like how a female laughter is different from a male laughter: The female laughter was one of dissent; it was not clear what the male laughter was. Presumably it represented patriarchy and its power relations. Presumably again, man laughed for the system, woman laughed against it.

The entire laughter discourse in India is not likely to be the same as it was before the Renuka moment. Renuka herself said the prime minister’s mythological allusions were an insult to women at large. It seems to me, that is not quite true. If you laugh at someone, surely you must be prepared to be laughed at, too, no matter what your gender is?

The fact is, social media in India has turned most topics into a binary format. It is nearly impossible to talk about anything without attaching gender politics to it. Perhaps this is historical correction. Again, perhaps not. If a joke can’t offend, what good is it? Surely, the corrective potential of humour is that it is not correct?

To my mind, the binary nature of Indian discourse is seemingly a simplistic way of saying, ‘handle us with care, we are of the feminine gender’. And I would venture to think that assumption of victimhood is surrender.

C.P. Surendran is a journalist based in India.