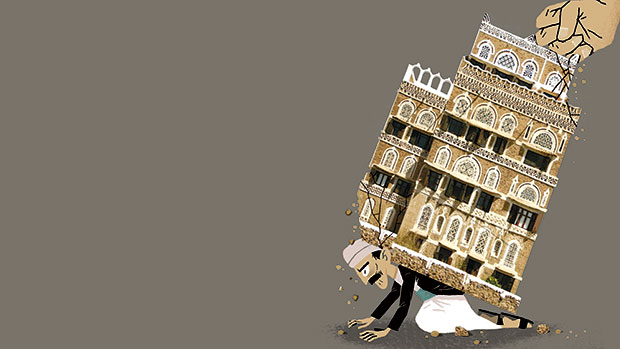

Has Yemen turned into a failed state or will it take more assassinations and explosions to confirm this status? Yemen may have actually succeeded in passing an exam enroute to gaining the status of a failed state, despite the presence of several competitors in the region and the continuation of political and military vibrations at such a fast pace that sometimes it is difficult for an average citizen to keep track or analyse. These disturbances have become part of the daily routine for the peoples of the so-called Arab Spring states.

The American writer Noam Chomsky’s characterisation of a failed state may already apply to Yemen, where the government has failed to protect its citizens and achieve stability and security for them. Therefore, allegations about practicing indirect violence and terrorism using hidden political forces may not be devoid of truth. Yemen has now become a threat not only to its citizens but also to neighbouring countries as it has turned into a hotbed of violence and terrorism internally, which is being exported to other countries. Perhaps the video released by a member of Al Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), Harith Nadari, claiming responsibility for the attack on the French magazine Charlie Hebdo last week confirms that.

This gives the US the strongest and most stable alibi to intervene in Yemen under the pretext of eliminating Al Qaida terrorism and giving legitimacy to the drone strikes and even direct military intervention, if necessary. But that may increase the number of innocent victims and make Yemen even more vulnerable politically, economically and socially.

External intervention may not seem the perfect solution to the crisis engulfing Yemen. The current American strategy that is based on the targeted killings of Al Qaida suspects through the use of drones cannot be condoned under international law, even if it is claimed that it is in the interest of the people of Yemen. This, especially since the number of innocent people who have died in these attacks is in the hundreds.

The National Foundation for the Victims of Drones in Yemen has confirmed, according to a report released in 2014 by the British human rights organisation Reprieve, that the drones that miss the targeted person re-strike at the same person more than a dozen times, which leads to casualties during every failed strike, and all targets have “died” on average more than three times before the “actual death” in a drone strike.

The number of victims reached 164 people, including women and children. The report indicates that 17 people were targeted more than a dozen times, such as Qassem Al Rimi, Nasser Al Wuhayshi, Ebrahim Al Asiri and Abdul Raouf Al Dahab. And none of them is dead yet. Does foreign interference in Yemen represent protection for the Yemeni people or is it actually a cause of their destruction?

One view might suggest that outside interference in the movement of people may push them towards paths that they have not chosen voluntarily, which may reduce their movement and expose them to failure. Most often the outsiders draw certain lines when it comes to achieving their interests, which may contradict with the interests of the people. And here, a collision takes place between the two parties — and this is already occurring in Yemen.

US President Barack Obama’s strategy in the fight against terrorism in Yemen has mainly been based on directing drones to get rid of Al Qaida suspects. Although the list of wanted men has shrunk considerably, the use of the drones has not stopped; rather it has expanded greatly in recent times. This is especially after allegations in the media that the US government allied with Al Houthis to eliminate Al Qaida in Radaa and specifically in the village of Khibisa by providing air cover, which helped Washington get rid of Al Qaida suspects and provide support to strengthen Al Houthis so that they back the current authority chaired by President Abd Rabbo Mansour Hadi. Hadi is a loyal US ally, just like the former Yemeni president.

While Al Houthis are accustomed to declaring their fight to be against government corruption and denouncing the Yemeni government’s links to the US, they found it convenient to overlook such alliances if they served their purpose of getting rid of both the Islah tribal militias and Al Qaida, in Radaa or in Marib, which probably will be the scene of the next conflict in the coming days.

The freezing of the GCC initiative and the role of the Gulf states — whether declared or undeclared — inside Yemen confirms that the Gulf states up to this moment have not been able to achieve stability in Yemen as a result of the complexity of interests and lack of clarity on the legitimate political actors in the country. Indeed, according to the description of Abdul Karim Al Eryani, political advisor of the president, the Gulf initiative is a creation of Yemenis themselves and thus, cannot be considered trustworthy. The lack of confidence in foreign interference and the inexactitude of its success in solving Yemen’s problems through the visions of different Yemeni groups confirms that the rebuilding of the country must begin from the inside. The weakness of the Yemeni government and its lack of credibility and legitimacy after the revolution of 2011, the entry of Al Houthis into Sana’a in November last year, the exit of the Islah party from power, and the emergence of Al Qaida from Abyan and Shabwa to Hadramout, Al Baida and Marib confirms that Yemen has become a centre for illegitimate political and military forces. Some of them came to power by force, while others came through nominal democratic standards that lacked true political participation. Some groups lost their positions partly or completely, such as Islah and the Al Muatamar party. Then there are forces beyond all legitimacy, led by Al Qaida and its associate Ansar Al Sharia. These forces are all responsible for what is happening in Yemen — the assassinations, bombings, murders, illegal use of influence and financial, administrative and military corruption.

Series of assassinations

The bombings and assassinations in Yemen are not new; the country has witnessed such crimes in the past, both before and after reunification both in northern and southern Yemen. But these incidents were limited in the past and centred mainly around the leadership at the top of the political pyramid. After the unity in 1990, these incidents became one of the methods adopted by the different political parties to get rid of their opponents.

Most of those who were murdered after the unification were active members of political parties, particularly the Yemeni Socialist Party. That phenomenon was repeated after the revolution of 2011 to include elements outside the circle of the Socialist party, including many Al Houthis and non-Al Houthis.

Who has an interest in such assassinations that destroy Yemen’s stability and security, apart from causing the deaths of innocents? In an informal interview in 2002, the late Mohammad Abdul Malek Al Mutawakil (a respected academic and activist who was assassinated in November 2014 in Sana’a), confirmed that the conflict in Yemen, which was centred around that period between the northern and southern leaders after the 1994 war, could not be sustained until a peaceful dialogue was adopted. His model at that time was the “Document of Pledge and Accord” that was signed in Jordan and was considered by Al Mutawakil as the future blueprint for all Yemenis. This document was killed at birth.

Al Mutawakil continued to assert his belief in peaceful dialogue even after the revolution of 2011, however, there were those who did not believe in this and that may have led to his assassination. He was unarmed when he was killed. The same tactic was applied to another defender of the principle of peaceful dialogue within Aden, Khaled Junaidi, the brain behind the Aden protests that demanded independence for the south. Even he was not carrying a weapon when he was assassinated.

Those assassinations were designed to send a message that peaceful dialogue may not work in Yemen, and could entrench a culture of the use of violence in Yemeni society to regain rights or for protection or revenge, whether this is utilised by political groups or ordinary individuals. The lack of any deterrence or fear when it comes to killing people could lead to repercussions against the rights of people, and the violation of freedoms in Yemen at all levels.

The latest report by Reporters Without Borders in 2014 with regard to press freedom reveals that Yemen has enjoyed more freedom of expression since Hadi took over from Ali Abdullah Saleh as president in February 2012. But a range of armed groups (Al Qaida, Al Houthis, southern separatists) have been responsible for an upsurge in threats and violence against the media.

But the media coverage includes fallacies more than it introduces us to facts. A report issued by the Freedom Foundation for media freedom, rights and development in Yemen “in cooperation with the US Middle East Partnership Initiative” explained that current Yemeni media coverage had slumped to new lows in spreading the culture of hatred, incitement and violence, specifically during November 2014. That month saw Al Houthis takeover of Sana’a. Some regard it as the beginning of a new phase in violence in Yemen. Surprisingly, despite the political and military confrontations between the different groups, specifically in Sana’a, they are all united around their hidden goal of diluting the problem of the south in a systematic attempt to eliminate the idea of secession or the revival of the southern state.

For the southerners themselves, the problem is not searching for a new identity in the midst of what is happening in the northern provinces. Their problem is searching for a ‘Southern Command’ that is conscious, impartial and far removed from the issues of the past and one that is capable of dealing with the multiple powers in the north.

The current differences between the cadres and leaders in the southern movement with regard to the confrontation and future plans for the proposed southern state confirm that the idea of separation is still an elusive goal. In a statement, the General Secretary of the Supreme Supervisory Commission in Aden, Ali Musabi, said that the failure to choose a united leadership could lead to the imposition of one by force, without exclusion or marginalisation of any party that does not sound logical or realistic. There is evidence that a united political front, which took shape in October 2014 under the name “the Supreme Council of the Revolutionary Movement for the Peaceful Liberation and Independence of the South” revealed a lack of trust between the parties shortly after the announcement.

The instability in Yemen, and the change in positions between now and then, makes it difficult to achieve specific political goals. Yemen is moving on a path that is intertwined with the interests of other countries. Therefore, it may be seen by outsiders as a danger that should be avoided or accessible booty that must be exploited to the hilt. One thing is for sure: The various political forces inside Yemen will not rest politically or militarily u

The culture of violence in Yemen and the fall of a state

nless they achieve their ambitions and will not be satisfied unless they come first in a terrible race to a fake summit, which may represent the end of Yemen as a state.

Haifa AlMaashi is a former professor at the University of Aden and a senior researcher in ‘b’huth’ (Dubai).