Some of former British prime minister Gordon Brown’s old lieutenants — martial metaphors, so cheap in politics, are warranted in their case — nowadays mount a strange defence of his decade-long fight with Tony Blair. By stymieing and sometimes undermining a prime minister from his own Labour party, the then chancellor made the opposition Conservatives irrelevant. The only stories were intra-Labour stories; the only compelling protagonists were employed by the two men. The rougher Brown became, the less the country needed Tories to check the Blair imperium.

As a theory, it is shameless, self-serving and plausible. A government is only truly commanding when it provides its own opposition. Blair had Brown. Margaret Thatcher had her Wets and freethinking chancellors.

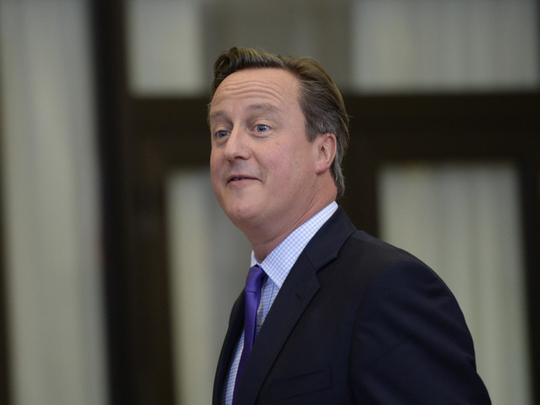

And Prime Minister David Cameron has an embarrassment of riches. Since renewing his premiership in May, he has already revised or delayed legislation to satisfy his own dissenting MPs. His plan to cut tax credits, income supplements for the low-paid, is being resisted by colleagues and newspapers, including proudly right-wing ones. Before he has even commenced his renegotiation of Britain’s European Union membership, ministers are pressing for the licence to recommend exit in the subsequent referendum from within the cabinet. If they attain critical mass — a third of the cabinet, say — he will not be able to deny them.

Then there is the competition to succeed him, which officially does not exist. Boris Johnson, the London Mayor, and Theresa May, the Home Secretary, are among those with an incentive to woo activists and mark themselves out from Cameron in the coming years. A tougher line on Europe or the related sore of immigration is the obvious way.

If these are the fissures five months after a giddy election win, imagine them in midterm, the low ebb in any government’s life cycle. Cameron, who is cushioned by a small parliamentary majority, can console himself with two thoughts. One is that George Osborne, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, is bound in: The prime minister’s struggles are the chancellor’s struggles. This historical oddity remains the most unusual thing about the government. Westminster has waited years for these two friends to fall out, but then the boxing world waited years for the Klitschko brothers [Vladimir nd Vitali] to fight each other. Sometimes two people really are as close as they profess to be; sometimes the normal competitive pressures do not apply.

The other consolation inverts the Brownites’ cheeky line of defence. As long as they simmer and never erupt, Conservative squabbles can deprive Labour of any relevance it has left after electing the unelectable Jeremy Corbyn as leader. There is such a thing as an optimal level of dissent: Too little and the official opposition fills the vacuum, too much and things fall apart.

Achieving that balance is easier when the dissenters are as biddable as Tory MPs of recent vintage tend to be. Most criticism of the leadership now emanates from the party’s moderate left, sensible right and the hard-to-place. It is usually reluctant and comes packaged with constructive advice. There is affection for Cameron among the 2015 intake, many of whom owe their seats to his electoral appeal, and a belated and grudging respect among previous cohorts too. This is not the bludgeoning Tory right of infamy, always primed with another “final” demand. Accommodations can be made if the prime minister is supple enough.

If he manages it, Labour could become a play that nobody wants to watch. All meaningful politics will take place inside the governing party; each outbreak of spite between the courts of Downing Street and the Home Office will draw more fevered analysis than a dozen opposition announcements, however worthy.

Merely to command a hearing amid the Tory rumpus, Labour will have to say and do ever wackier things. The Conservatives only made a dent in the news during the Blair-Brown years by comporting themselves extremely or eccentrically. It took years for the stain on their name to lift. Exchanging seriousness for distinctiveness is never worth it for a party that aspires to govern; Corbynism only makes sense when you realise that it aspires to no such thing.

Politics is full of truisms that are not actually true. A week is not a long time in politics; much more stays the same than changes. People do not vote for hope and vision, but for the lesser evil. And nobody really minds a divided party. Division, managed properly, can convey vitality while draining opponents of a reason to exist. There is no solace for Labour in the Tories’ coming strife.

— Financial Times