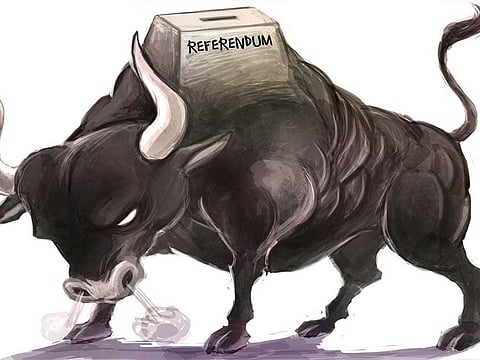

The Catalonia vote is a bigger threat to the EU project than Brexit

Spain threatens to break up the euro unless Catalan nationalists come to heel

While the EU watches in disbelief, a remote threat has mushroomed suddenly into an existential crisis. It is even more intractable than Brexit, and certainly more dangerous.

The volcanic events unfolding by the day in Catalonia threaten the EU project within its core. They pose a direct threat to the integrity of monetary union.

Former French premier Manuel Valls — son of a celebrated Catalan painter — warns that today’s banned vote for independence vote will lead to Catalan secession, and it will be “the end of Europe” as a meaningful mission. Those old enough to remember the Spanish Civil War can only shudder at TV footage of crowds across Spain cheering units of Guardia Civil as they leave for Catalonia, egged on with chants of “go get them”.

As matters stand, 14 senior Catalan officials have been arrested. There have been dawn raids on the Catalan Generalitat, including the presidency, the economics ministry, and foreign affairs office. Officials preparing for the vote have been interrogated. The Guardia Civil has been deployed to seize ballots sheets and to prevent the referendum from taking place, if necessary by coercive means. The Catalan security forces — Mossos de Esquadra — have told the Spanish authorities that they will not carry out orders to shut down voting sites if this leads to civil disorder. Their higher duty is Catalan cohesion, or “convivencia ciutadana”. It is defiance, a little like the British army’s Curragh Mutiny in March 1914. The government of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy insists that the Guardia Civil is being sent to preserve the constitutional order and inviolable integrity of Spain. Catalonia’s leaders call it fatally-misguided repression that risks spinning out of control. “We will never forget what has happened. We will never forget this aggression, this prohibition of opinion,” said Carles Puigdemont, the Catalan leader. The contrast with the Scottish referendum in 2014 is self-evident. Markets have yet react to this showdown even though the Spanish finance minister, Luis de Guindos, has openly warned that Catalonia will suffer a “brutal pauperisation” if it presses ahead. He said the region would suffer a collapse in GDP of 25 per cent to 30 per cent, a doubling of unemployment, and a devaluation of up to 50 per cent once it had been thrown out of the euro.

This is a threat, not a prediction. Such a collapse would occur only if Spain chose to bring it about by making life hell for the Catalan state: by closing its economic borders, by using its veto in Brussels to ensure that Catalonia cannot rejoin the EU or remain in monetary union, and by blocking Catalan accession to global bodies such as the International Monetary Fund.

The problem for Spain is that if it acted in such a fashion, it would bring a commensurate catastrophe upon itself. Catalonia is the richest and most dynamic region of Spain — along with the Basque country — and makes up a fifth of the economy. Such circumstances would entail a partial break-up of the euro, re-opening that Pandora’s Box. The status of Spain’s sovereign debt would be unclear. Why would the Catalans uphold their share of these liabilities if subjected to a boycott? Markets would have to presume that the debts of the rump kingdom would no longer be 99 per cent of GDP but more like 120 per cent. This burden would be borne by a poorer society and one that would necessarily be in an economic slump itself.

The Bank Of Spain played down the crisis on Thursday, saying only that Spanish borrowing costs would rise if tensions worsened. “It would initially affect the sovereign risk rating, and afterwards spread through other interest rates,” it said.

It is not for foreigners to take sides in a historical dispute of such emotion, drenched in mythology, with the wounds of Franquismo and Las Jornadas de Mayo raw to this day. Catalan nationalists date the original sin to 1714 when Philip V abolished their institutions and imposed Castilian laws — and absolutism — by right of conquest. What seems clear is that Rajoy and his Partido Popular have provoked a Catalan backlash by blocking enhanced devolution that had already been agreed with the outgoing Socialist government. What the Catalans want is a settlement on the Basque model with their own budget and tax-raising powers.

Rajoy then exploited the Eurozone banking crisis to try to break the power of the regions, forcing Catalonia to request a 5 billion euros (Dh21.7 billion) rescue even though it is a net contributor to the Spanish state. He has since hid behind mechanical legalism.

You might equally blame the Catalan nationalists for charging ahead with a referendum barred by the constitutional court, creating a mood of division between “Remainers” and “Leavers”. Yet they were sorely provoked. Rajoy’s response has since been so inept that he may have created a majority for independence where none existed before. The problem for the EU is that it is a prisoner to legal rigidities. Commission chief Jean-Claude Juncker has had to back Rajoy and the Spanish constitutional order because that is how the EU system works. This has made Brussels a party to alleged abuses in Catalan eyes. Barcelona’s mayor Ada Colau — who opposes secession — has called on called on the EU to “defend the fundamental rights of Catalan citizens against a wave of repression from the Spanish state”.

“Europe cannot allow itself to adopt a passive position over the Catalan question, seeing that the events going on in Barcelona are affecting Paris, Madrid, Brussels, and Berlin alike,” she wrote in The Guardian. We will find out today whether or not the Catalan people turn out to queue defiantly at locked polling stations, manned by the Guardia Civil. A declaration of unilateral independence is not yet “on the table”, said Puigdemont. Not yet. The EU is in a bind. It faces a rule of law crisis in Hungary and Poland. It faces an East European revolt over migrant quotas. Its relations with Turkey have turned hostile. Now Spain is threatening to break up the euro unless the Catalans come to heel. Brexit is the least of their problems, and one that can be solved so easily with an ounce of common sense.

— The Telegraph Group Limited, London 2017

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard is International Business Editor of The Daily Telegraph. He has covered world politics and economics for 30 years, based in Europe, the US, and Latin America.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox