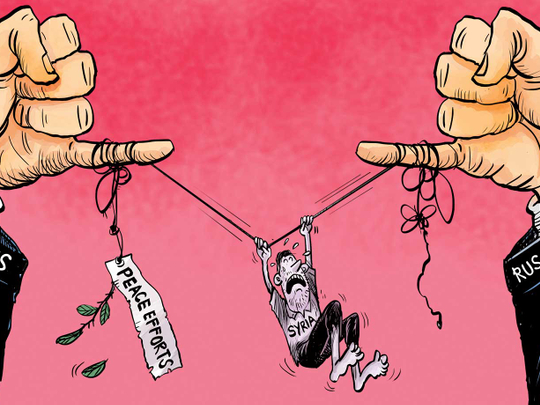

Washington and Moscow are engaged in a new standoff over Syria, and this time it has gone beyond words. The US has broken off talks and recalled its negotiators from Geneva. Russia, meanwhile, has suspended an agreement on the destruction of plutonium, setting conditions — including an end to Ukraine-related sanctions — for the resumption of the accord.

Cue doom-mongers, mostly on the western side, warning that US-Russia relations are every bit as bad as they were during the darkest days of the Cold War, with corresponding dangers for everyone else. Some, indeed, would argue that the risks are greater still, because the restraint forced by the prospect of “mutual assured destruction” and any formal framework for contact are both missing. Of course, the return to hostilities in and around Aleppo is a catastrophe for those on the ground and a fresh setback for those trying to oust President Bashar Al Assad.

Where US-Russian relations are concerned, however, there are reasons to take a less apocalyptic view, and the same applies to the wider consequences. If the fiercest measure the US has taken is to break off somewhat fitful talks on Syria, and the strongest response Russia has chosen to offer is the suspension of a single arms agreement that Moscow anyway accuses Washington of breaking, that says a lot in itself.

It could reflect how little the two countries currently have to talk about, in which case a break makes little difference. Or, more likely, it shows their concern to spare other areas of cooperation, such as wider arms control or the space station. Indeed, the US said talks about avoiding bilateral clashes in Syria would continue, while the conditions Moscow has set for resuming the plutonium deal suggest it is open to bargaining even as it stamps its foot. To an extent both sides are playing to their domestic galleries.

This is an often neglected aspect of many a diplomatic spat, but it is especially true of this one. The US is in the grip of a highly unusual presidential campaign that has barely a month to run. While US President Barack Obama is not running, the charges of foreign policy weakness levelled against him, not just by Donald Trump and the Republicans but by some on his own side, are a factor in the campaign.

It is important for Obama and his legacy, but still more so for Hillary Clinton’s prospects, that the Democratic administration does not appear spineless — especially not before its old Russian foe. Russian President Vladimir Putin, for his part, has to attend to national morale in the face of the first fall in living standards for many Russians since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

This is judged to be such as risk that there is talk he could bring forward the presidential election to next year. Neither he nor his foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, can afford to play too nice with the Americans.

But there is another reason why the health or otherwise of US-Russia relations should not be judged exclusively by their talks about Syria: to believe that the two countries are capable of ending the conflict in Syria is to believe that the Cold War continues, and that every war is a proxy superpower war. We are living in different times, and Syria is not a Cold War-era conflict.

It is wider than that, with many different proxies involved, and loyalties shifting to and fro; it is also narrower, in the sense that the only settlement that will stick must be acceptable to the people who live there. Outside powers cannot force a peace so long as the parties to the dispute believe they still have ground to gain. If the conflict has demonstrated anything, it is that neither erstwhile superpower has the clout to control its clients on the ground.

The latest ceasefire failed not only because the US mistakenly bombed a contingent of Syrian troops, and not only because an aid convoy was destroyed, but because the sponsors of the deal — the US and Russia — were unable to control what happened next. The US clearly cannot marshal its so-called moderates, and may not even be quite sure who they are.

Something similar applies to Putin and Al Assad. From the wording of the US state department’s announcement on breaking off talks, it would appear that even Washington is starting to accept that Putin cannot just switch Al Assad on or off. There may well still be diehards — in the Pentagon, perhaps, and the Russian ministry of defence — who believe the world is still theirs to fight over and divide up between them. The failed ceasefire illustrated something different: that US-Russian sponsorship is no longer enough.

For any ceasefire in Syria to endure, let alone any settlement, either many more parties will have to be involved as sponsors — including Iran, Saudi Arabia and Turkey — or the Syrians themselves will have to call a halt. That may not happen until there is a victor. This is not a palatable thought.

But it may be the case that the US-Russian peace efforts in Syria have to be seen as a laudable effort, but one that was ultimately doomed to fail. Not because the US and Russia could not agree, but because an old-style superpower deal is no longer enough. This may not be good news for Syria, but it does mean it need not be the sole gauge of US-Russian relations. There are hints Moscow and Washington understand this, even as they trade recriminations.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Mary Dejevsky is a writer and broadcaster and a member of the Valdai Group and a member of the Chatham House think tank.