Syria is a European crisis as well as a Middle Eastern one, and the world’s worst human rights disaster in decades. Historians may one day tell us to what degree the west wasted a chance to force Bashar al-Assad to the negotiating table, had sufficient and timely pressure had been brought to bear on his forces, in particular through targeted strikes. That’s how Slobodan Milosevic was forced to sign the 1995 Dayton agreement, which put an end to mass atrocities in Bosnia.

In the summer of 2013, a window of opportunity was arguably lost as a result of American hesitation. If archives are ever opened up, we may learn that it was the US failure to uphold red lines over chemical weapons use in Syria that emboldened Russia’s Vladimir Putin to launch his military intervention in support of a dictator whose army had been massacring civilians since 2011.

British restraint, or rather abstention, on Syria predated Barack Obama’s. And France, whose fighter planes were ready to take off in August 2013, could hardly go it alone. Still, trying to connect the dots between the Middle East, Russia, Europe, and how the US chooses to act or not act, remains important. The ravages of war in Europe’s vicinity, and the spillover effect of Middle Eastern chaos, are developments whose impact is yet to be fully measured.

There have been half a million deaths in Syria, and we’re still counting. We are all connected to these atrocities in ways that go beyond our on-and-off capacity for indignation as we sit watching television images of children being bombed in their hospital beds in eastern Ghouta.

Syria will haunt us for a long time yet. Since the fall of Raqqa last year, the crisis has gradually mutated into something resembling a world war, although the large powers involved in it — Russia, Iran, Turkey, the US — aren’t expressly in open warfare with one another. But they are vying for territorial control. Some experts like to draw a comparison with Lebanon’s 15-year conflict — by which measure Syria may be only at the midpoint of its proxy war.

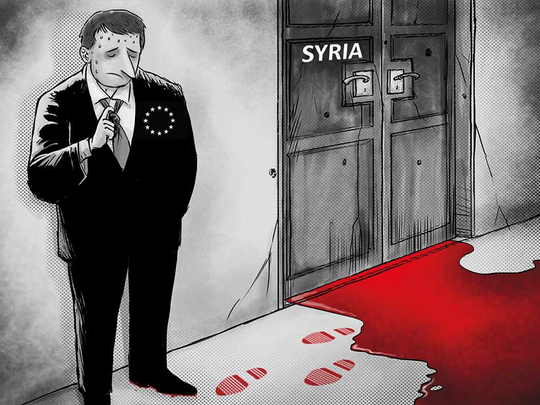

Europeans are largely sidelined, however vocal our political leaders may at times choose to be. We haven’t yet fully fathomed how Syria’s catastrophe has affected how we relate to the world, to ourselves and to the values we like to profess. After 1945 we said “never again”, but never again is unfolding right before our eyes. Syria has become the absolute demonstration of our helplessness, and we collectively let that happen. Syria is the vortex in which a rules-based global order is fast unravelling. That should matter to us immensely because Europe has always had a greater stake in the UN system than the US has. When rules crumble, as happened with the 1930s League of Nations, we are well aware how beasts can rear their heads.

Syria is where autocrats and neo-totalitarians are winning the day right now. Putin, Recep Tayyip Erdogan of Turkey and Iran’s military theocracy hold the high ground — or are widely perceived as doing so, which matters perhaps even more. No matter the human cost, nothing stops a leader for whom the end justifies the means. Civilians aren’t civilians: they’re “terrorists”. UN resolutions aren’t law: they’re just paper — stuff that can usefully lower the outrage of mushy liberals before bombers get back to the business of creating a desert that will be called peace.

From the very beginning, Syria was too complex a crisis to identify sound allies, goes that thinking. The west is guilty, full stop. Sanctions and the stemming of financial flows can end the conflict. Just talk and negotiate. What we are witnessing is a dizzying European passivity and powerlessness in the face of total war unfolding just a few hours away. Of course, there are condemnations, statements by foreign ministers, and calls of “something must be done”. But our societies have fallen prey to inertia and confusion.

One day we will need to look back more closely at the chronology of events in which counter-terrorism, not the UN-backed notion of the “responsibility to protect” civilians, became the sole priority of the West; and in which military intervention against Daesh became politically palatable in 2014 not because Arabs and Yazidis were being butchered, but because western hostages had been beheaded. We’ll need to dig into how the necessary questioning of the west somehow morphed into widespread indifference to what authoritarian powers can get up to.

Syria is a tragedy for the West not because it has occasionally awakened our righteous outrage, nor because Europe’s politics have been upended by refugee arrivals. Syria is very much part of the West because, while we like to believe we have looked at ourselves in the mirror after Europe’s 20th-century carnage, we’ve let a degree of nihilism creep into how we approach the hell that has been let loose not far from our borders. We’ve almost inoculated ourselves against shame. Syria is the West’s moral defeat.

— Natalie Nougayrede is a columnist and writer.